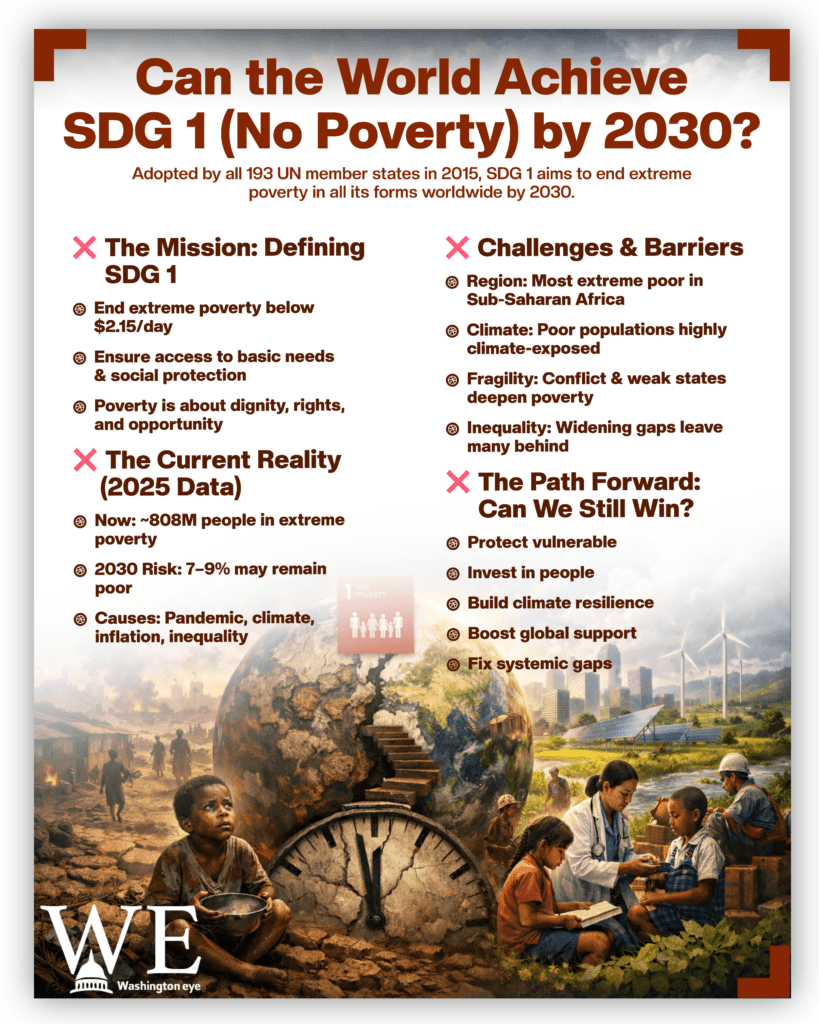

With just five years left until the deadline to achieve the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), the world faces an urgent and difficult question: Can the world realistically deliver on “No Poverty”, SDG Goal 1, by 2030? Adopted in 2015 as part of the 2030 Agenda, SDG 1 commits all 193 UN member states to end extreme poverty in all its forms, provide social protection, and reduce the proportion of people living in poverty by at least half by the year 2030.

The core ambition of SDG 1 is sweeping: no one should live in extreme poverty, defined by the international poverty line as living on less than $2.15 per day, and all people everywhere should have access to necessities such as food, shelter, healthcare, clean water, and education. This goal acknowledges poverty as a multidimensional issue, not just about income but also about dignity, opportunity, and access to rights.

However, progress has slowed dramatically in recent years, making the 2030 target increasingly out of reach. According to United Nations statistics, around 808 million people, or roughly one in ten people worldwide, were living in extreme poverty in 2025, with significant disparities across regions. Even if current trends hold, nearly 7–9 percent of the world’s population could still be trapped in extreme poverty by 2030.

This slowdown is the result of overlapping global crises, a “polycrisis” that has reversed or stalled gains made over the past decades. For more than two decades, poverty rates declined steadily, but this progress stalled around 2015, and the COVID-19 pandemic, climate shocks, global inflation, conflicts, and rising inequality have set development back substantially. Millions of people slipped back into poverty as national economies contracted, unemployment rose, and social safety nets were overwhelmed.

Regional divides are stark. Sub-Saharan Africa alone accounts for a disproportionately high share of the world’s poor, housing an estimated 67 percent of people living in extreme poverty, despite making up only a fraction of the global population. Conflict-affected states, fragile economies, and climate-vulnerable regions face some of the steepest barriers, with poverty deeply entrenched and social protection systems weak or non-existent.

Beyond income measures, multidimensional poverty shows how lack of education, health care, safe housing, clean water, and energy further traps families in cycles of deprivation. A 2025 UNDP report revealed that roughly 887 million people in multidimensional poverty are directly exposed to climate hazards, linking environmental vulnerability with deep-rooted socioeconomic disadvantage.

The global rich-poor divide remains a central structural issue. While high-income countries have advanced social protection and economic resilience, low-income nations struggle with weak governance, limited economic diversification, and high debt burdens. Inequality, both within and between countries, has widened the gap, meaning that even if aggregate global indicators improve, the most vulnerable populations remain far from the finish line.

Despite the daunting picture, many experts stress that failure is not inevitable. Ending poverty by 2030 will require accelerating action on multiple fronts simultaneously:

- Expanding social protection systems to ensure coverage for the vulnerable and marginalized, especially women, children, and people with disabilities.

- Investing in education, healthcare, and job creation to build human capital and economic opportunity at the community level.

- Strengthening climate resilience and disaster risk reduction to prevent environmental shocks from pushing people deeper into poverty.

- Global cooperation that ensures sufficient development financing, fair trade, and technology transfer to lower-income countries.

- Public-private partnerships and inclusive policies that target structural inequality, support small businesses, and improve access to credit and markets.

It is also critical to address systemic issues such as economic exclusion, land rights, and financial inclusion, barriers that keep many households in chronic poverty. Sustainable pathways are emerging where governments, civil society, and the private sector work together to build resilient, inclusive economies with a focus on long-term prosperity rather than short-term growth.

As the world races toward 2030, the next five years will be decisive. The challenges are enormous, but so too is the potential for transformative change. Whether SDG 1 will be met depends not only on data and targets but on political will, global cooperation, and the concerted effort to leave no one behind.