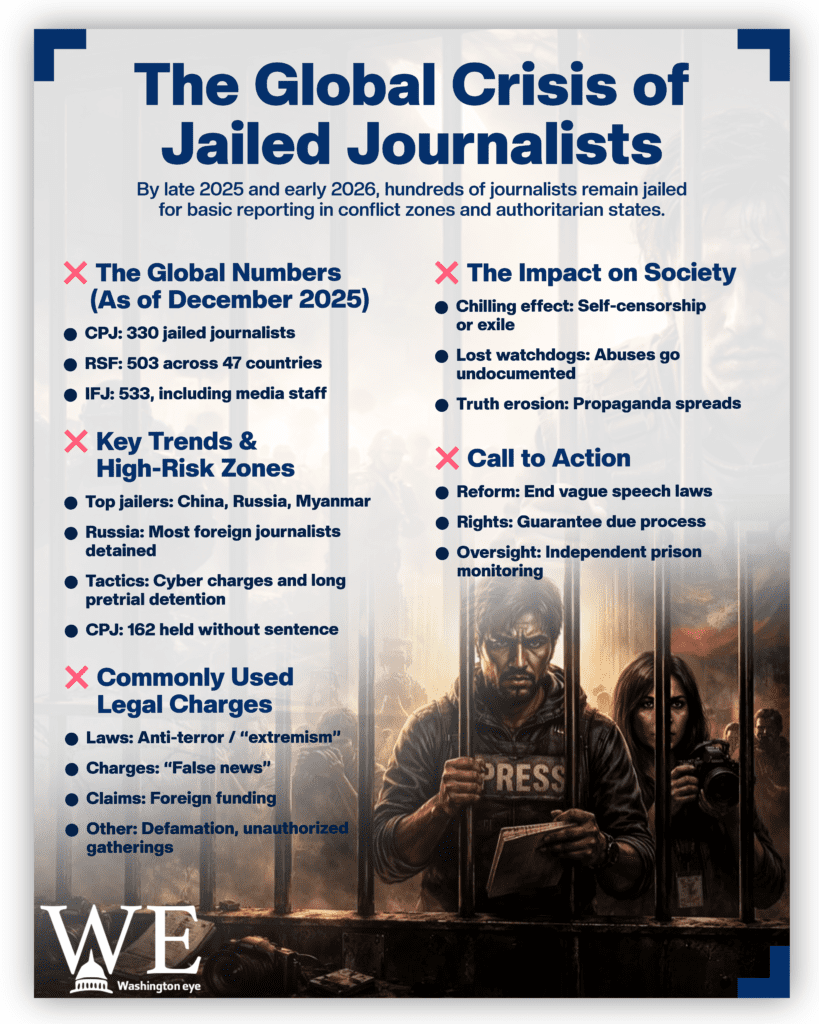

The number of journalists behind bars worldwide remains alarmingly high, with press-freedom groups warning that imprisonment has become a routine tool to silence scrutiny in both authoritarian states and conflict zones. New annual counts published in late 2025 and January 2026 show hundreds of reporters and media workers detained or imprisoned, often for doing basic newsgathering: interviewing sources, documenting protests, or reporting on war, corruption, and abuses.

The latest global “prison census” from the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ) counted 330 journalists imprisoned as of Dec. 1, 2025, a snapshot CPJ says reflects a mix of intensifying authoritarian repression and escalating armed conflict. CPJ also highlighted harsh and sometimes life-threatening prison conditions, and reported that nearly half of those jailed (162) were being held without a sentence at the time of the count; an indicator, the group says, of how pretrial detention itself is used as punishment.

Another leading watchdog, Reporters Without Borders (RSF), reported 503 journalists detained in 47 countries as of Dec. 1, 2025, a higher number partly because RSF’s methodology and categories differ from CPJ’s. RSF said the largest prison for journalists remained China (121), followed by Russia (48) and Myanmar (47), and noted that Russia held the most foreign journalists in the world. The International Federation of Journalists (IFJ), which also tracks imprisoned “journalists and media staff,” published a detailed list showing 533 imprisoned in 2025 (as of late December), again reflecting differing definitions and coverage across monitors.

Even when totals vary, the underlying pattern is consistent: jailings surge where governments treat independent reporting as a political threat. CPJ’s previous count for Dec. 1, 2024, found 361 journalists behind bars, near the modern record, and pointed to crackdowns tied to war, political instability, and expanding “national security” prosecutions. Rights groups say the effect is the same across systems: detention chills coverage, empties newsrooms, and pushes remaining journalists toward self-censorship, exile, or silence.

The reasons governments cite are often framed as public safety or state protection: anti-terror laws, “extremism” charges, spreading “false news,” foreign-funding allegations, defamation, or participation in unauthorized gatherings. In practice, watchdogs argue, these accusations frequently overlap with a journalist’s beat; covering protests, exposing graft, reporting on minority rights, or documenting civilian harm in conflict. Recent cases in Europe and Eurasia, including renewed detentions around protest coverage and “extremism” prosecutions, show how quickly criminal law can be aimed at routine reporting.

Conflict has also sharpened the risks. While killings draw urgent attention, imprisonment is increasingly the longer, quieter crisis: journalists are arrested at checkpoints, detained after publishing battlefield reporting, or held under emergency rules. UNESCO has repeatedly warned that crisis and conflict environments amplify threats against journalists and that impunity and pressure on independent reporting rise during instability. These conditions often coincide with mass arrests and restrictions on movement and access.

Analysts say today’s jailings reflect both old tactics and newer ones. Authoritarian states have long used prison to crush dissent, but the modern playbook often relies on legal “grey zones”: prolonged pretrial detention, sealed evidence, special courts, and digital-era offenses like “misinformation” or “cyber” charges. CPJ’s 2025 snapshot noted that a significant share of jailed journalists face long terms, and many remain locked up for years without a final verdict, an approach that can punish reporting without the burden of proving a case in open court.

Press-freedom advocates argue the stakes go beyond the media industry. When journalists are jailed, they say, communities lose watchdogs who document corruption, police violence, unsafe working conditions, election manipulation, and war crimes. The result is a weaker public record, fewer verified facts, and wider space for propaganda and rumor. Watchdogs are urging governments to repeal or narrow vague speech-related crimes, guarantee due process, and allow independent monitoring of detention conditions, steps they say are essential if press freedom is to recover in 2026 and beyond.