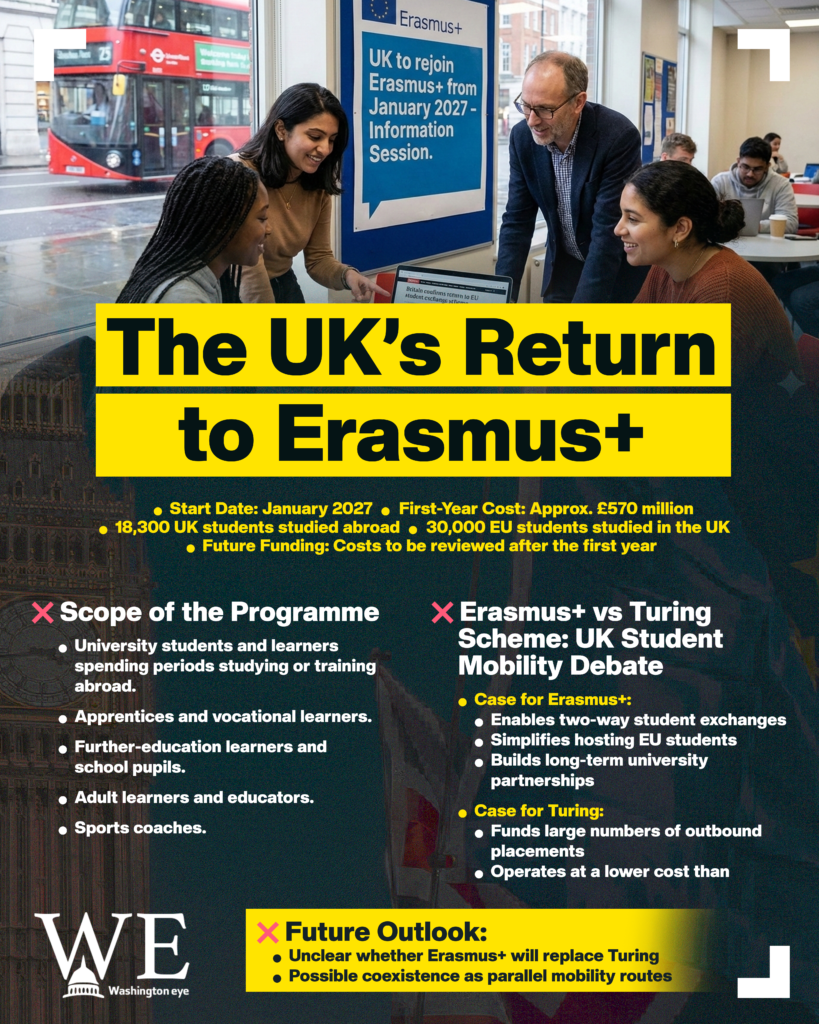

Britain will rejoin the European Union’s Erasmus+ student exchange programme from January 2027, the UK government confirmed this week as part of a wider push to “reset” relations with Brussels after years of post-Brexit friction. Under the initial agreement, the UK will pay about £570 million for the first year of participation. Officials said future costs will be agreed later, but the headline figure has already triggered debate in Westminster and across the higher-education sector about value for money and what the UK gets in return.

Erasmus is one of Europe’s best-known mobility programmes, enabling students and learners to spend a period studying, training or working abroad with grants and administrative support. Crucially, Erasmus+ is wider than universities: it covers apprentices, further-education learners, school pupils, adult learners, educators and even sports coaches, a breadth that the UK government says will help open international opportunities to people who might otherwise be priced out.

The move also closes a politically sensitive chapter that began at the end of the Brexit transition. In December 2020, the UK government under then-prime minister Boris Johnson decided not to remain in Erasmus+ and instead launched the Turing Scheme, arguing it would be more global in reach and better tailored to UK priorities. A parliamentary briefing at the time noted the formal shift away from Erasmus+ and the creation of Turing as its replacement.

Supporters of rejoining argue that Erasmus+ brings advantages that are hard to replicate through a national programme alone: long-standing institutional partnerships, simplified placement pipelines, and two-way flows that make it easier for UK campuses to host students from across Europe as well as send British participants abroad. In the last full year before Brexit disruptions, 2018–19, roughly 18,300 UK students went to the EU on Erasmus placements while about 30,000 EU students came to the UK, according to figures cited in UK reporting on the deal.

Critics, however, point to cost comparisons with the Turing Scheme. Recent UK sector reporting says Turing has supported tens of thousands of outward placements annually on a budget far below the new Erasmus re-entry bill, raising questions about whether Erasmus despite its brand and infrastructure delivers proportionate returns for the taxpayer.

The government’s case rests on access and reciprocity. While Turing primarily funds UK learners going abroad, Erasmus+ is designed around mutual exchange and system-wide cooperation. Ministers say the 2027 return will widen participation beyond traditional “year abroad” students to include vocational routes and shorter work placements, with an emphasis on enabling young people “from all backgrounds” to take part.

Politically, the announcement lands as Prime Minister Keir Starmer’s Labour government seeks practical, deliverable areas of cooperation with the EU without reopening the question of rejoining the bloc. Erasmus+ is symbolically potent (a visible benefit many families recognise) but also technically feasible: the programme already includes non-EU countries through association agreements, which helped make the UK’s return negotiable despite Brexit’s red lines.

For universities, colleges and employers, the stakes are broader than travel. Advocates say mobility improves language skills, employability and cross-border networks, soft-power assets for a country that wants to remain academically competitive and globally connected. For students, the biggest impact is often personal: a funded chance to study or train abroad without taking on extra debt, and to build international experience at the start of their careers.

The first participants will not depart until 2027, but institutions are likely to start planning well before then rebuilding partnerships, aligning calendars, and preparing guidance on eligibility and funding. With costs beyond year one still to be finalised, the next phase of the debate will centre on whether the UK can secure a longer-term financial settlement that matches participation levels and whether Erasmus+ can coexist with Turing or eventually supersede it as the UK’s flagship outward-mobility pathway.