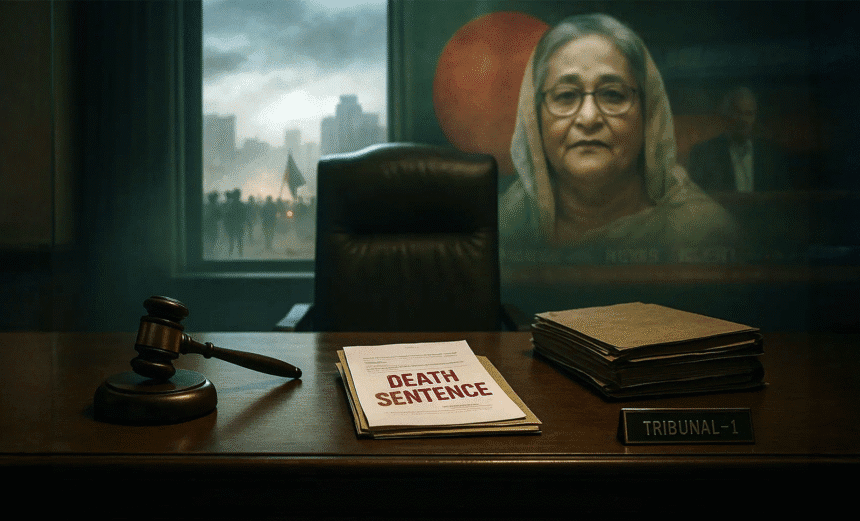

Bangladesh was shaken on 17 November 2025 after a special tribunal in Dhaka handed down a death sentence to former Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina, finding her guilty of crimes against humanity linked to the deadly 2024 student uprising that toppled her government. The verdict, delivered by the International Crimes Tribunal-1, marks the most dramatic judicial decision in the country’s history and the first time a former head of government has been sentenced to death in absentia.

Hasina, who ruled Bangladesh for nearly 20 years across multiple terms, was accused of ordering and overseeing a brutal crackdown on students protesting civil-service job quotas, a movement that evolved into a nationwide revolt. According to reports presented in court and cited by international agencies, as many as 1,400 people were killed when security forces allegedly used live ammunition, drones, tear gas, and helicopter support to disperse protestors during July and August 2024. Rights groups had long blamed elite units, particularly the Rapid Action Battalion, for enforced disappearances and extrajudicial killings, and the Tribunal concluded that Hasina, as head of government, bore command responsibility for the violence.

Hasina was not present in court. She has been living in India since fleeing Bangladesh in August 2024 following the collapse of her government amid uncontrollable civil unrest, defections from within her party, and pressure from the military. The Tribunal found her guilty on several counts: three carrying the death penalty and others carrying life imprisonment. Her former Home Minister, Asaduzzaman Khan, was also sentenced to death in the same case. Bangladesh’s interim administration, currently led by Nobel laureate Muhammad Yunus, has requested Hasina’s extradition from India, but New Delhi has yet to decide on the politically sensitive issue. Indian officials have signaled concerns over stability, asylum obligations, and regional diplomatic consequences, especially given Hasina’s long-standing ties with India during her years in office.

The verdict carries immense historical weight. Hasina first became Prime Minister in 1996, returned to power in 2009, and subsequently ruled uninterrupted until her fall in 2024. Under her leadership, Bangladesh achieved remarkable economic growth, expanded infrastructure, and improved social indicators, but her government was also criticized for increasing authoritarianism. Opposition parties accused her of manipulating elections, curbing press freedom, arresting rivals, and suppressing dissent through strict laws such as the Digital Security Act. The 2024 student protests, initially focused on job quota reform exposed widespread frustration with governance, corruption, and inequality. As demonstrations swelled across university campuses and streets, the situation escalated into one of the deadliest episodes in modern Bangladeshi history. The Tribunal ruled that Hasina personally authorized the deployment of lethal force and failed to prevent systematic abuses by security agencies.

Bangladesh has been tense since the verdict was announced. Dhaka saw scattered explosions, arson attacks, and clashes between security forces and supporters of the now-banned Awami League, which cannot contest the upcoming 2026 elections under the interim government’s directives. Police have intensified patrols across major cities as shopkeepers closed markets early and universities suspended classes. Human rights observers have warned that the verdict may push the country toward deeper polarization unless accompanied by transparent appeals processes and national reconciliation efforts. Families of victims of the 2024 violence have welcomed the ruling as long-awaited justice, while Hasina loyalists call it a politically motivated attempt to erase her legacy.

International response has been swift and divided. The United States, European Union, and several rights organizations expressed concern over the use of the death penalty and emphasized the need for due process, even while acknowledging the gravity of the charges. India, whose decision on Hasina’s extradition could reshape regional politics, urged all sides to exercise restraint. China called for “stability and continuity” in Bangladesh’s political transition, while Pakistan and several South Asian nations urged the interim government to ensure fairness and prevent further violence. Global analysts say the verdict could redefine how South Asian governments balance political accountability with democratic stability, especially as Bangladesh prepares for elections in February 2026.

Despite the severity of the sentence, analysts say Hasina’s execution remains unlikely unless India agrees to extradite her, something considered improbable in the short term. Yet the political symbolism of the ruling is profound, signaling a decisive break from the Hasina era. It underscores the interim administration’s commitment to addressing the human rights abuses of the past. Bangladesh now stands at a crossroads, navigating the delicate terrain between justice, political restructuring, and societal healing as it enters a new and uncertain chapter.