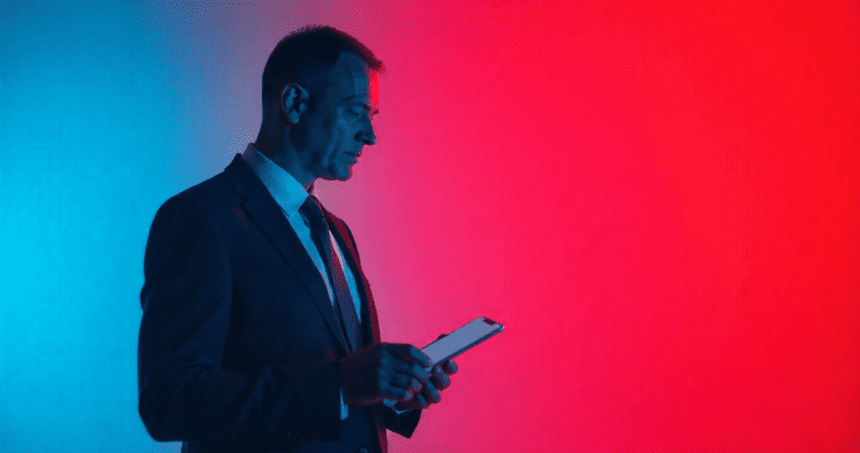

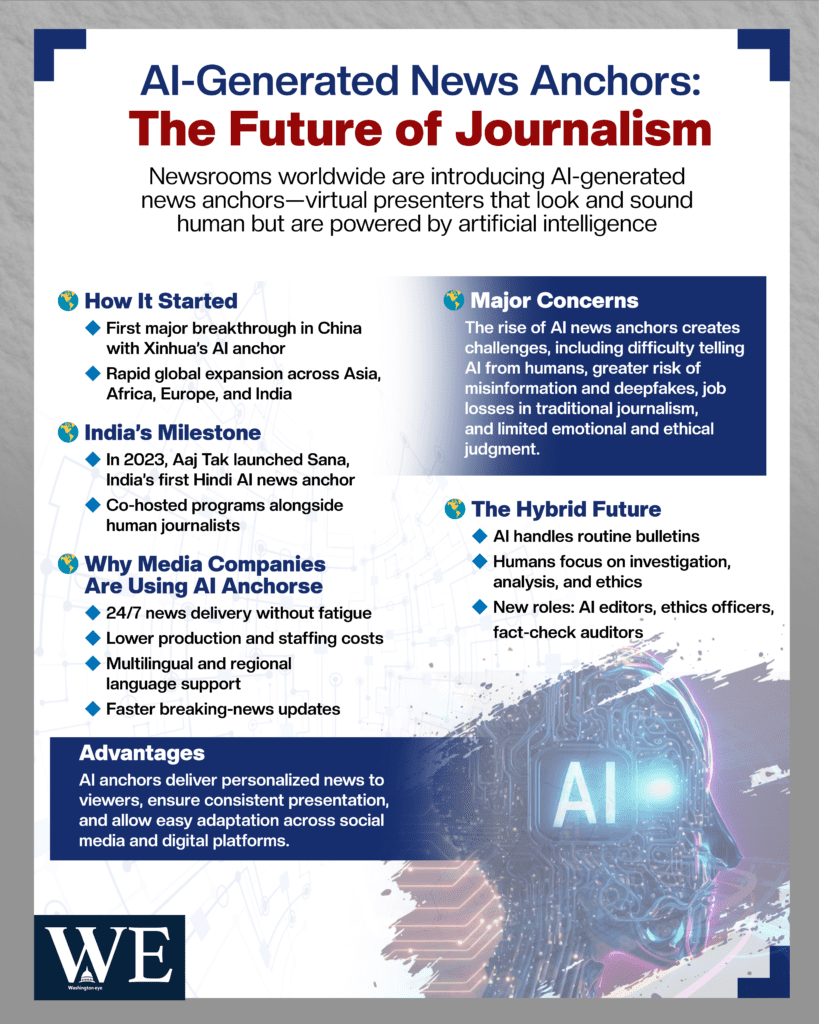

In 2025, newsrooms around the world are increasingly experimenting with artificial intelligence to generate news anchors, virtual presenters that look, speak, and behave like humans but are powered entirely by algorithms. From China to India and Africa to Europe, broadcasters and digital platforms are deploying AI anchors to supplement, and in some cases replace, human presenters in a bid to cut costs, accelerate news delivery, and broaden audience reach.

The trend first gained attention in the late 2010s, when China’s state-run Xinhua News Agency partnered with Sogou to unveil an AI newscaster capable of mimicking human facial expressions and voice inflection. Since then, the technology has improved rapidly, with companies and news outlets worldwide announcing AI anchors that can operate 24/7 and in multiple languages.

In March 2023, India’s Aaj Tak, part of the India Today Group, introduced Sana, the nation’s first Hindi AI news anchor, who was rolled out publicly alongside traditional broadcasts and went on to co-host shows such as Black & White. Sana’s launch underscored both the technological capabilities and symbolic weight of AI in mainstream media.

Similarly, industry sources note that Africa saw its first AI anchor, Alice, developed by the Centre for Innovation and Technology (CITE), demonstrating that AI media personalities are no longer confined to wealthy or tech-dominant nations. Supporters of AI anchors argue that the technology addresses several long-standing challenges for news organizations. In an era of shrinking news budgets and fierce competition for audience attention, AI presenters can deliver news 24 hours a day across platforms, from TV to social media, without fatigue or salary costs. For global networks, AI anchors can automatically switch between languages and regional accents, theoretically expanding viewership without hiring large translation and broadcasting teams.

Moreover, AI can personalize news delivery. Imagine a viewer tuning into a local broadcast where the AI anchor already knows the viewer’s language preference, interests, or even schedule needs. Proponents claim this could drive deeper engagement, especially among younger audiences less inclined toward traditional anchor-led broadcasts. However, the rise of AI anchors also raises significant concerns across credibility, ethics, and employment. One fundamental question is trust: can audiences reliably distinguish between a human and AI presenter? A 2025 report by Euronews noted that hyper-realistic AI anchors have begun “fooling the internet,” with some viewers unable to tell that what they are watching isn’t human-generated.

This blurring of artificial and real media poses risks in an age already plagued by misinformation and deepfake concerns. To address this, regulators in the European Union have included transparency obligations under the AI Act, requiring providers of synthetic media to disclose when content is artificially generated, including news anchors.

Journalistic credibility also hangs in the balance. Traditional anchors are journalists first, trained to understand context, verify sources, show empathy, and make judgment calls. AI anchors, by contrast, are as good as the data and prompts they receive. Errors in reporting, biased training data, or poorly framed stories could spread widely without human oversight, undercutting public trust. Critics argue that AI should be used only as a tool to assist human journalists, not to replace them at the front of the broadcast.

Unions and media professionals have raised alarms. In many markets, broadcasters argue that the technology could lead to job displacement, with routine news reading and headline delivery automated out of existence. Others counter that new roles will emerge: AI news editors, prompt engineers, deepfake auditors, and ethics compliance officers may soon be part of newsroom staffing charts. Some media outlets are already experimenting with hybrid models. Human journalists are working alongside AI anchors, writing scripts, fact-checking content, and stepping in for nuanced reporting while AI handles standardized bulletins and multilingual versions of stories. This blend seeks to combine human judgment with technological efficiency.

There are broader geopolitical considerations too. In Ukraine, for example, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs appointed Victoria Shi, an AI spokesperson based on a real public figure, to disseminate official consular information, signaling governmental use of synthetic presenters beyond commercial newsrooms. As 2025 draws to a close, the conversation around AI anchors is moving beyond novelty to serious debate about the role of artificial intelligence in public discourse.

Will news consumers embrace virtual presenters as credible and engaging? Can engagement gains outweigh the risks to journalism’s ethical foundations? And ultimately, can AI deliver not just information, but insight? The technology is here to stay, but its integration into journalism will be shaped as much by cultural expectations and regulatory frameworks as by the capabilities of the underlying models.