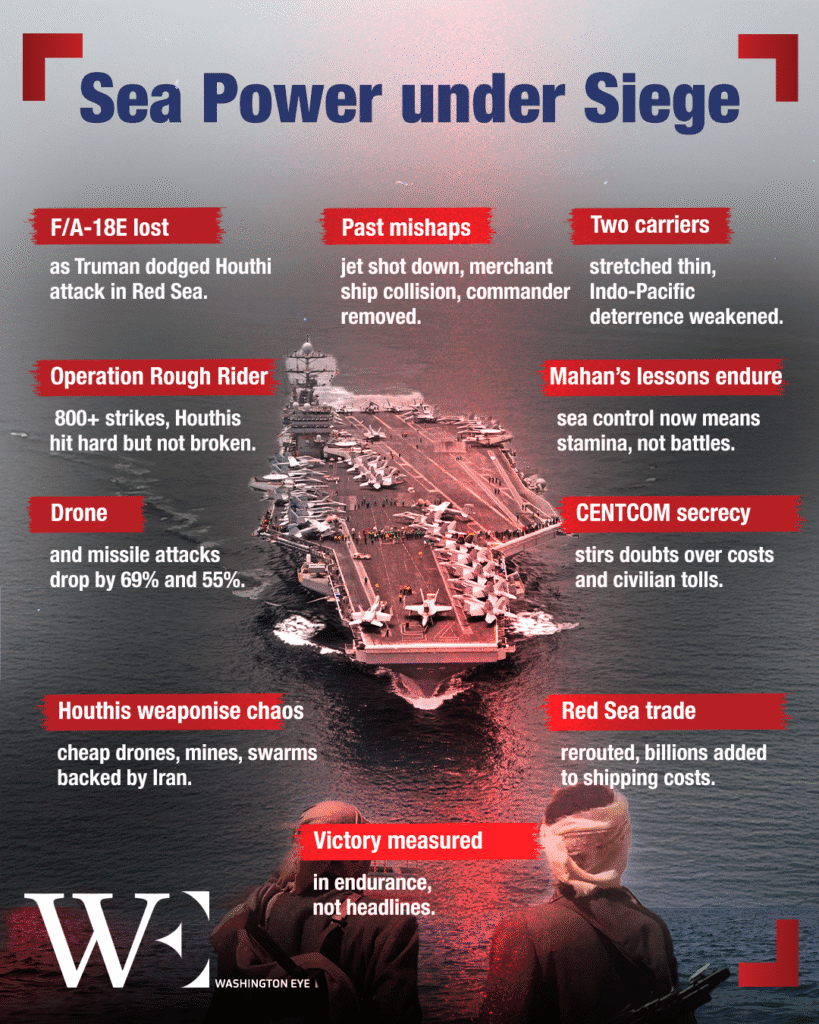

The U.S. Navy has long embraced the principles set out by Alfred Thayer Mahan: control the seas, protect trade routes, and use maritime dominance to influence world affairs. Now, more than a century after Mahan’s theories shaped global naval strategies, the United States finds itself in a hard test of sea power’s limits — battling an asymmetric enemy in the Red Sea while trying to uphold freedom of navigation across one of the world’s most vital maritime corridors.

This reality came into sharp focus again this week when the USS Harry S. Truman, a Nimitz-class aircraft carrier deployed to the Red Sea, lost an F/A-18E Super Hornet and a tow tractor overboard. According to the Navy, the mishap occurred during an aircraft move inside the hangar bay. A sudden hard turn, reportedly made to evade incoming Houthi fire, contributed to the loss.

It was a stark reminder: maintaining command of the seas today often means fighting an elusive enemy whose tactics defy conventional naval operations.

A String of Mishaps Under Pressure

The Truman’s recent accident is not an isolated event. In December, the carrier lost another F/A-18 fighter jet — this time shot down accidentally by the USS Gettysburg, a cruiser operating alongside it. The incident forced two aviators to eject, fortunately with only minor injuries. In February, the Truman collided with a merchant vessel near Port Said, a congested gateway to the Suez Canal, resulting in the removal of its commanding officer and urgent repairs in Souda Bay, Crete.

Each incident reveals more than human error; they expose the punishing tempo and dangers of high-stress naval operations under real-world combat conditions. With adversaries adapting faster and operating from the shadows, even the world’s most powerful navy faces vulnerabilities that Mahan himself might not have foreseen.

The cost is mounting. A single Super Hornet fighter jet costs between $60 million and $70 million. Beyond hardware losses, however, the strategic cost is growing: a drain on readiness, morale, and U.S. maritime influence.

Operation Rough Rider: Proving Sea Power’s Utility — and Its Limits

The Truman’s deployment, originally planned to conclude earlier this year, was extended by Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth in March to sustain pressure on the Houthis. This extended campaign, dubbed Operation Rough Rider, has resulted in more than 800 U.S. airstrikes against Houthi targets across Yemen.

According to U.S. Central Command (CENTCOM), the strikes have significantly degraded Houthi capabilities: ballistic missile launches have dropped by 69%, and kamikaze drone attacks by 55%. Hundreds of Houthi fighters and key leaders have been killed, and crucial facilities — such as missile depots, radar sites, and command centers — have been destroyed.

Yet even as the military touts tactical success, the broader strategic picture remains stubborn. Shipping companies remain wary. The Red Sea is not fully secure. The Houthis, battered but unbroken, continue to adapt and attack.

This echoes a fundamental Mahanian principle: sea power is not just about striking blows, but about sustaining influence over time. Success is measured less by spectacular victories than by control of the economic arteries of the world — and by denying that control to adversaries.

The Houthi Threat: A New Kind of Naval Challenge

Emerging from the mountainous regions of northern Yemen, the Houthis — formally known as Ansar Allah — have mastered asymmetric warfare. While the United States commands aircraft carriers and stealth bombers, the Houthis rely on relatively cheap drones, ballistic missiles, and fast attack boats to threaten global trade.

Their tactics are simple but effective: swarm attacks, maritime mines, anti-ship missiles, and saturation drone strikes. They don’t need to win a battle at sea — they need only to raise the cost of shipping to unsustainable levels. In this, they have partially succeeded: since late 2023, global trade through the Red Sea has plummeted, forcing vessels to reroute around the Cape of Good Hope, adding weeks to transit times and billions to global shipping costs.

Moreover, Iran’s backing has allowed the Houthis to sustain and evolve. Smuggling networks transport drones, missile parts, and sophisticated electronics into Yemen. The Houthis have even refined their own weapons systems, demonstrating ingenuity with limited resources.

This resilience is precisely why airstrikes alone, no matter how intense, may not fully neutralize the threat. And it explains why, despite massive firepower, the U.S. Navy remains locked in an exhausting game of cat-and-mouse.

Sea Power Today: A Test of Strategic Patience

Mahan’s vision of sea power emphasized more than just battleships and blockades; it stressed the broader economic and psychological effects of maritime dominance. Sea control was not simply about sinking enemy ships — it was about securing global commerce, ensuring political influence, and shaping the world order.

In the Red Sea today, the U.S. is attempting precisely that. Keeping carrier strike groups on station is not about fighting decisive battles; it’s about keeping trade flowing, reassuring allies, and denying the Houthis — and by extension Iran — a strategic victory.

Naval power acts as an invisible hand, quietly regulating commerce and exerting pressure. But such a strategy requires time, resources, and a public willing to support long, ambiguous campaigns. In the age of instant results and limited patience, this is a harder sell than it was in Mahan’s day.

Operation Rough Rider’s results — a decrease in Houthi attacks, but no outright defeat — perfectly illustrate the slow-grind nature of maritime influence. It’s not about winning in a month; it’s about wearing down adversaries over years, until their strategic position collapses.

Strain on the Fleet: Hidden Costs

Maintaining two carrier strike groups — the Harry S. Truman and the Carl Vinson — in the region is an extraordinary commitment of military assets. Usually, such a deployment signals preparation for a major war. Instead, it is now necessary simply to protect commercial shipping from insurgent threats.

This deployment is draining American resources that might otherwise be positioned to deter China in the Indo-Pacific. It is burning through precision munitions stockpiles already strained by commitments in Europe and other theaters. Some in Congress are openly questioning whether the U.S. Navy can sustain this operational tempo without long-term degradation.

Meanwhile, CENTCOM’s limited public disclosure about the campaign — citing “operational security” — has raised questions about civilian casualties, financial costs, and the broader endgame. Unlike previous operations, such as the 2023 task force Operation Prosperity Guardian, there has been less visible effort to rally international support, further isolating the U.S. in the court of global opinion.

Mahan taught that control of the seas must be part of a broader national strategy, aligned with political, economic, and diplomatic efforts. The risk now is that U.S. naval power is achieving tactical victories but losing strategic momentum.

A Modern Maritime Dilemma

The situation in the Red Sea represents a classic maritime dilemma: how to project overwhelming power against a dispersed, irregular opponent who needs only to disrupt, not defeat, a superior navy.

The Houthis have shown adaptability, ideological commitment, and a willingness to absorb punishment. Their partnership with Iran extends their endurance. Their successes — relative though they may be — validate Mahan’s warnings about the dangers posed by even small forces operating against vulnerable trade routes.

Moreover, their campaign illustrates how non-state actors can today contest control of strategic chokepoints once thought secure. In doing so, they challenge not only American maritime dominance but the assumptions underlying globalization itself.

Sea Power’s Enduring — and Evolving — Importance

The ongoing confrontation between the U.S. Navy and the Houthis reveals much about the enduring relevance of sea power — and its evolving challenges.

Mahan argued that whoever controls the seas controls world commerce and, ultimately, world power. Today, control looks different: it’s about ensuring the safe passage of tankers and container ships against drone attacks and hidden missiles. It’s about sustaining presence, absorbing losses, and demonstrating endurance longer than the enemy can resist.

The USS Harry S. Truman‘s misfortunes are part of that larger story: proof that command of the seas remains vital but is no longer uncontested. It demands constant vigilance, adaptability, and strategic patience.

In the Red Sea, the United States is not fighting to win a traditional war. It is fighting to uphold a system — the free movement of goods, the economic lifelines that bind the world together. It is fighting, in other words, to preserve the very conditions Mahan believed were essential to global leadership.

Whether that leadership can be sustained against a determined, resilient enemy remains an open question — one that will be answered not in a single battle, but over many months, and possibly years, of persistent naval presence.