The guns have not fallen silent in Tripoli—only shifted direction. Libya remains ensnared by the same ghosts that have long haunted its path to unity: fractured authority, unchecked militias, and a political framework dominated by armed actors masquerading as state institutions.

The assassination of Abdel Ghani al-Kikli—“Ghneiwa”—was not a passing episode in Libya’s tumultuous saga. It tore open the thin veil of control that Tripoli’s leaders attempt to project. Killed inside a military compound during what was described as a reconciliation meeting, Kikli’s death ignited fierce firefights between militias that extended beyond the capital’s core. The death toll quickly rose, and the street battles laid bare that far from peace, Libya is locked in an ongoing contest for supremacy—one now drawing reinforcements from the west and the east.

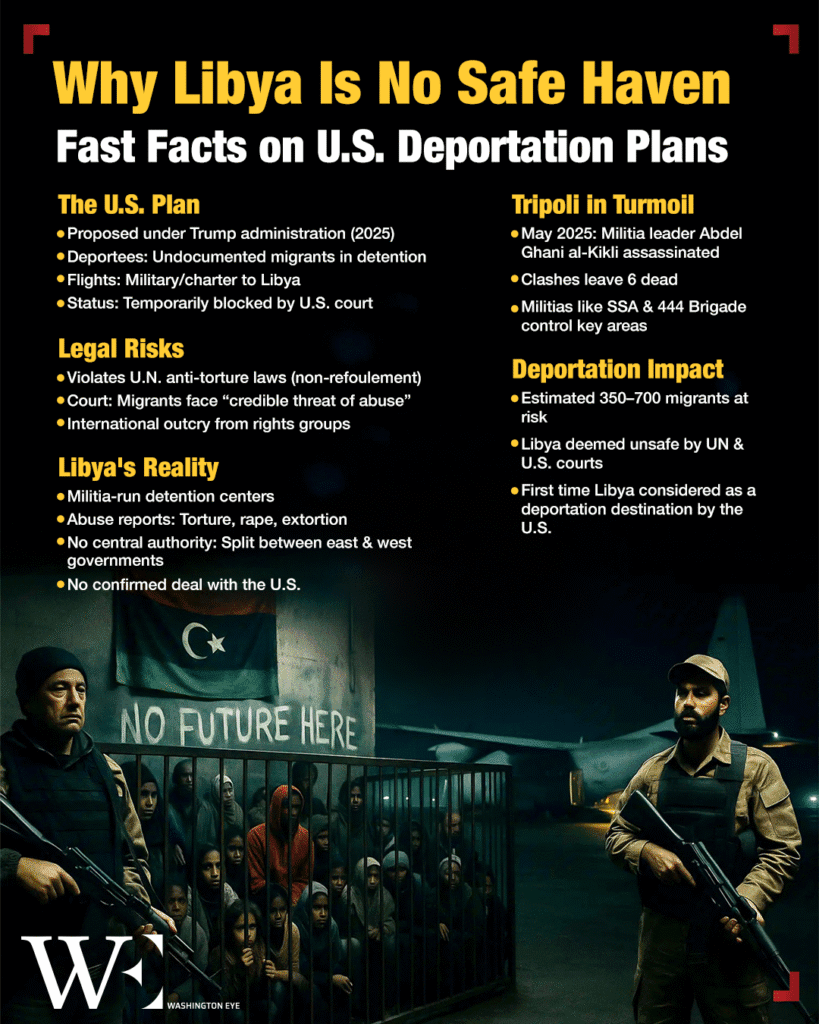

Kikli wasn’t an insurgent hiding on the margins. He led the Stability Support Apparatus (SSA), a militia with an official badge, sanctioned by the internationally recognised Government of National Unity (GNU). His forces controlled the Abu Salim district and operated with impunity under a state mandate. But beneath the badge was a darker truth: international rights groups have repeatedly accused the SSA of operating torture chambers, extorting migrants, and carrying out extrajudicial killings with little fear of reprisal.

His suspected killers, the 444 Brigade, are no less embedded in state structures. Commanded by Mahmoud Hamza, the brigade has long been favoured for operations against Islamic State remnants and even tasked with protecting diplomatic missions. But like most armed groups in Libya, their allegiance is transactional—owed not to a national flag but to networks of influence and revenue.

Ideology has never been the core currency of Libya’s war economy. Access is. Access to checkpoints, budgets, oil revenues, smuggling corridors, and the hard cash that flows through Libya’s fractured banking system. Control of Tripoli equals control of the purse strings, and with that comes power. Integration into government bodies gives these militias not legitimacy—but leverage.

This is why they fight. Not for a new Libya, but for the spoils of the old one. Each battle is a negotiation by other means—a repositioning for greater control of infrastructure that brings money and influence.

Against this backdrop, the recent U.S. proposal to deport migrants to Libya reveals a dangerous detachment from the country’s actual conditions. Court filings in early May confirmed that military flights to Libya were under discussion as a means to expel undocumented migrants. The idea provoked immediate legal backlash, and a federal judge stepped in to halt the plan. Still, the fact it progressed this far suggests either deep ignorance or deliberate disregard for Libya’s volatile state.

Neither of Libya’s rival administrations—whether in Tripoli or Benghazi—claimed to have agreed to the returns. Both appeared blindsided, reinforcing the uncomfortable truth that Libya is treated less as a sovereign actor and more as a sandbox for external powers to test policy.

Libya is not post-conflict. It is in a state of suspended violence—intermittent but always primed. The assassination of Kikli has only confirmed what those on the ground already know: that the country remains carved up by militias who shift between titles like “commander” and “minister” with ease, depending on what suits the moment.

And yet Western policymakers continue to operate as though Libya were stable enough to absorb external burdens—be they migrants or counterterrorism missions. It is a fallacy. Libya cannot be stabilised through diplomatic ceremonies or memoranda. It must be stabilised by dismantling the militia economy: by stripping away the protection rackets, the official titles granted to warlords, and the blurred lines between security and criminality.

Until then, every uneasy pause in fighting is simply a prelude. Every power-sharing deal built on illusion only deepens the rot. The flow of fighters—now coming in from the west and the east—signals that the battle for Tripoli is far from settled.

Because Libya’s war hasn’t ended. It’s still unfolding, block by block, checkpoint by checkpoint. The silence is only temporary—until the next shot breaks it.