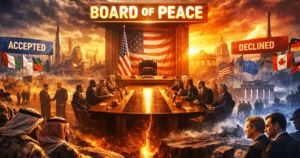

The warning by UN Secretary‑General António Guterres that women’s leadership in peace and security is “going in reverse” signals a deeply troubling shift, not simply a stall in progress, but a regression with broader consequences for conflict resolution, stability, and gender equality worldwide.

From Progress to Backsliding: Diagnostic of the Reversal

When Resolution 1325 was adopted in 2000, it was seen as transformative: it formally tied women’s inclusion to peace and security agendas. Over the past two decades, some advances were evident. The number of female UN peacekeepers has doubled, and women have increasingly participated in local mediation efforts and post‑conflict justice initiatives. Yet Guterres now cautions that those gains are fragile. He observed that nations often speak of inclusion and protection, but “fall far short” when real decisions are made.

More alarming indicators underscore the reversal. Last year, 676 million women lived within 50 km of deadly conflict events, the highest such figure in decades. Documented incidents of sexual violence against girls rose by 35 percent in some regions, and in certain settings girls represented nearly half of all victims. Meanwhile, as women’s civil society networks carry heavy burdens in crisis zones, many of those organizations are reporting severe financial distress. In one survey, 90 percent of women‑led local groups in conflict areas said they were underfunded; nearly half expected to close in six months.

Implications for Peace, Governance, and Gender Justice

The rollback of women’s leadership is not a symbolic or token issue, it undercuts the very effectiveness and legitimacy of peace processes. Empirical research increasingly shows that peace agreements backed by women’s involvement are more durable and inclusive. When women are excluded, agreements may neglect the needs of half the population, widening distrust and undermining reintegration and reconstruction.

At governance levels, the reversal risks deepening patriarchal control over security institutions. If women’s voices are sidelined in shaping disarmament, security sector reform, or community resilience, those policies may inadvertently replicate wartime divisions or fail to redress gendered harms. Moreover, the erosion feeds a discouraging narrative: that gender equality is nonessential or marginal, weakening broader efforts in education, economic participation, and rights protections.

The financial squeeze on women’s organizations strikes at the grassroots foundations of peacebuilding. When local women’s groups vanish, so too do early‑warning systems, mediation networks, and trust brokers between conflict parties and communities. The multilateral architecture that pledged support for women in conflict zones risks becoming hollow if power is vested only in traditional actors.

Paths Forward: Recommitment, Accountability, and Resilience

Reversing this negative trend demands more than rhetoric. Member states must translate commitments into national laws, policies, budgets, and implementation plans. Guterres has emphasized five priority areas: funding, participation, accountability, protection, and embedding commitments in law.

States must adopt measurable indicators of inclusion and violence prevention, and hold themselves accountable, not merely through reporting, but through transparent auditing of gender‑sensitive budgets. Civil society and women’s networks should be guaranteed predictable, multi‑year support to grow resilience, not be perpetually under threat.

Regionally tailored strategies can address contexts where backsliding is most acute. For example, Afghanistan’s systematic exclusion of women from public life shows how fragile gains can be reversed in the absence of robust institutional protections. In conflict zones like Sudan, Myanmar, Gaza, or the Occupied Palestinian Territories, the intersection of violence, exclusion, and funding cuts magnifies the risks to women and girls.

Ultimately, the reversal of women’s leadership in peace and security is a wake‑up call. It demands renewed political will, structural reform, and sustained investment. Without it, the world risks not just the exclusion of women from peace, but the undermining of peace itself.