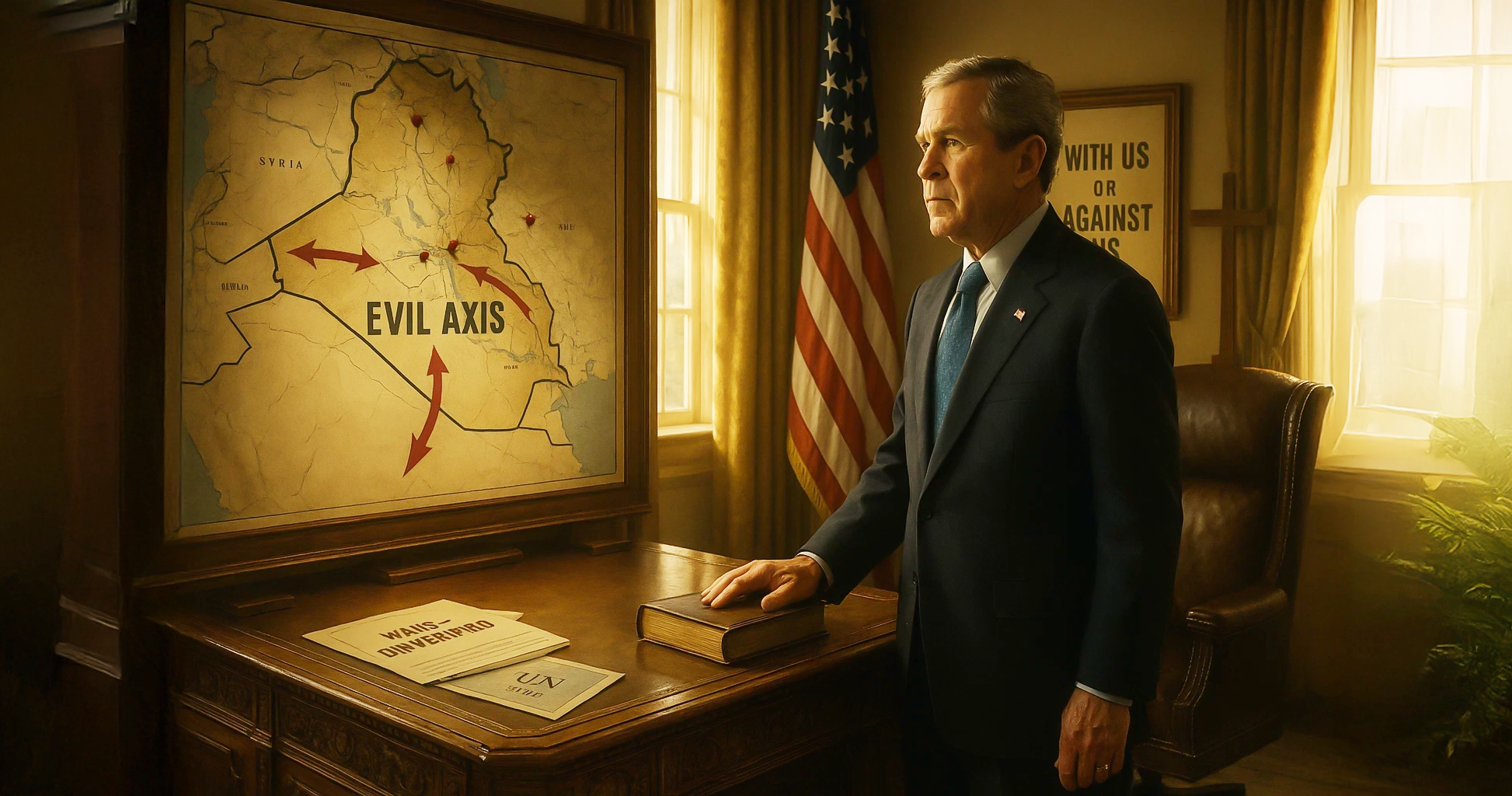

Newly declassified UK diplomatic files reveal a striking revelation: President George W. Bush framed the Iraq invasion as a religious mission, a “crusade” by “God’s chosen nation” aimed at eradicating “evil‑doers”, including Saddam Hussein. Sir Christopher Meyer, Britain’s ambassador to Washington, described Bush’s outlook as “Manichean”, portraying an uncompromising worldview where the global fight against terror was framed in stark moral terms.

This characterization deviates sharply from standard realpolitik. By invoking divine mission, Bush cast the war in transcendent terms, not merely as strategic necessity, but as a moral imperative. Such diction resonated domestically, especially after 9/11, tapping into a climate where national security and spiritual purpose could fuse.

Diplomatic Strains: Blair’s Caution vs. Bush’s Imperative

Britain, under Prime Minister Tony Blair, recognized early the political and legal perils of joining a war on such moralistic grounds. British officials, including Blair’s adviser David Manning, warned that the U.S. push risked Blair’s premiership and even parliament’s support if a second UN resolution was bypassed. Manning famously told U.S. advisors, “The US must not promote regime change in Baghdad at the price of regime change in London”.

While Bush enjoyed congressional backing and framed urgency in moral absolutism, Blair faced domestic political constraints. The contrast underscored a profound divide in transatlantic strategy: one side leveraged moral fervor to justify unilateral action, while the other feared domestic backlash and sought multilateral legitimacy.

Ethical Framing and the Erosion of Diplomacy

Bush’s portrayal of the war as a righteous mission had critical diplomatic consequences. According to UK diplomatic cables, this moral framing made it politically impossible to pause the military buildup unless Saddam Hussein surrendered outright. That effectively closed space for inspectors, compromise, or delaying tactics until “smoking‑gun” evidence emerged or UN approval was secured.

Furthermore, the crusade narrative served to marginalize skepticism from France, Russia, and others on the UN Security Council, recasting dissent as moral equivocation rather than legitimate caution.

Implications for Global Governance and International Law

Bush’s moral absolutism, and its embrace by key allies, reshaped international norms. By recasting war as moral necessity, it signaled a shift away from collective security institutions toward unilateral ‘moral’ diplomacy. The UN, designed to temper national impulses toward war, was sidelined in favor of a higher moral calling.

This is echoed in subsequent scholarly critique: while the establishment view said the moral clarity spurred necessary action, critics argue it masked deeper motives, natural resources, pre‑determined agendas, and power projection. The result? A legacy of weakened multilateralism, emboldened executive overreach, and diminished international trust.

Legacy: Lessons and Warnings

The revelations reaffirm many of the Chilcot Inquiry’s conclusions: flawed intelligence was leveraged to support moralistic rhetoric, diplomacy was prematurely abandoned, and the war proceeded on a narrative gap rather than a verified threat.

Today, these lessons carry profound resonance. They caution global leaders against moralizing war before exhausting diplomatic tools or multilateral mechanisms. They also highlight the peril of conflating national identity with divine sanction—a mistake whose consequences rezoned global power dynamics and destabilized entire regions.

These newly released UK records bring sharper focus to the moral lens through which the Iraq War was not just justified but driven at considerable geopolitical and institutional cost. They remind us that framing matters: the narratives leaders choose today may define the legitimacy, and fallout, of tomorrow’s conflicts.