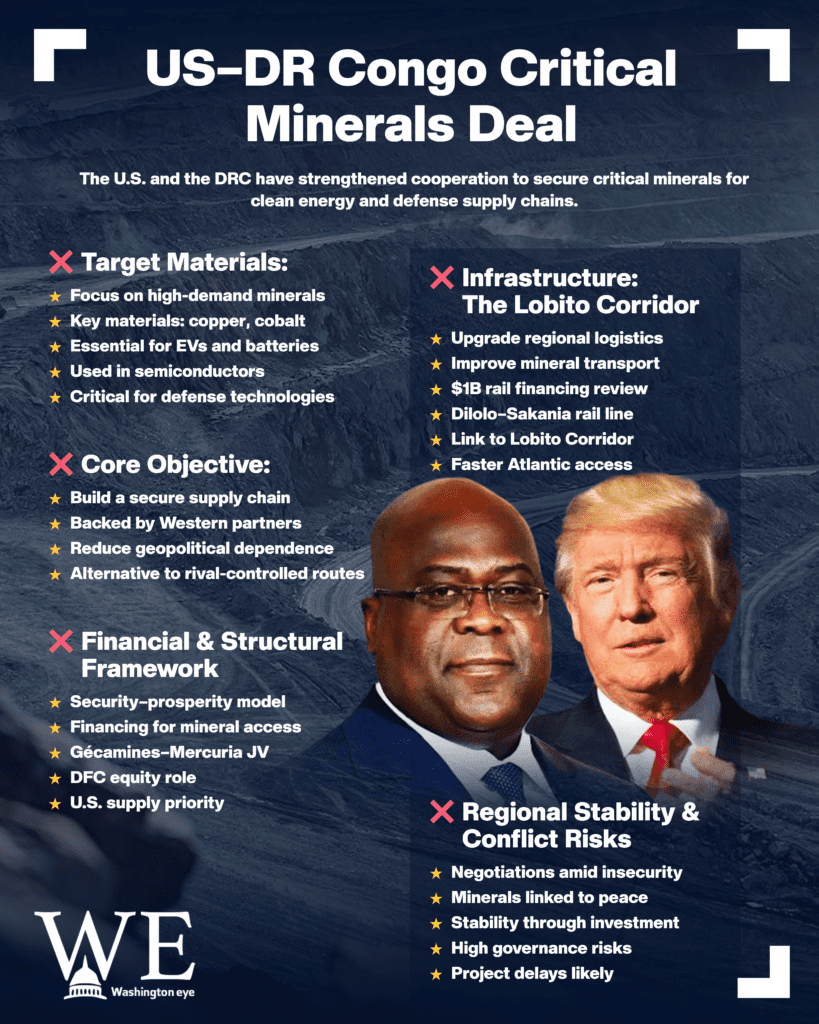

The United States and the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) have stepped up negotiations on a critical minerals partnership that would pair U.S.-backed financing with preferential access to Congolese copper and cobalt, materials central to electric vehicles, batteries, semiconductors, and defense technologies. The push gained momentum in early December 2025 in Washington, where the minerals track was framed as part of a wider “security and prosperity” package for a conflict-hit region whose mines sit at the heart of the global clean-tech supply chain.

At the center of the emerging deal is a proposed U.S. equity investment, via the U.S. International Development Finance Corporation (DFC), into a joint venture between Gécamines (DRC’s state mining company) and commodities trader Mercuria. The venture would market copper and cobalt (and potentially expand to other strategic minerals) and could give U.S. end-users a “right of first refusal” on supplies, a structure designed to lock in access without outright ownership of mines.

Money is a major driver. DFC said one related railway project in the DRC could seek up to $1 billion in DFC financing after review, aimed at rehabilitating and operating the Dilolo–Sakania rail line so it can connect into the U.S.- and EU-backed Lobito Corridor route to the Atlantic. Separately, a key Angola rail component of the corridor has already been backed by major funding: Reuters reported a $553 million DFC loan agreement, plus an additional $200 million from South Africa’s Development Bank of Southern Africa, to revamp Angola’s Benguela rail line and expand capacity tied to the Lobito logistics chain.

Why the urgency now is simple: the DRC is the world’s cobalt powerhouse, and the U.S. is trying to reduce dependence on China-dominated supply chains. Reuters noted Congo holds about 72% of global cobalt reserves and accounts for over 74% of supply, with a significant share linked to artisanal mining. For Washington, securing “friendly” supply is not only an industrial policy goal, but also a national security play, especially as cobalt, copper, and related metals underpin everything from grid storage to advanced electronics.

For Kinshasa, the pitch is equally strategic. Officials have long argued the country exports too much raw value while bearing the environmental and social costs. The U.S. framing; investment, infrastructure, and higher “local value capture”, aims to make the partnership politically sellable at home, particularly if it brings better prices, traceability, and downstream processing opportunities. DFC explicitly highlighted goals like improved transparency and competitiveness, and access to “responsibly sourced” materials.

The DRC’s recent domestic reforms underline the direction of travel. On December 19, Congo issued a decree halting artisanal copper and cobalt processing until operators can certify legal and traceable origin, part of an anti-corruption and anti-smuggling crackdown in a sector that supports millions but is notorious for leakages. The move may raise short-term compliance costs, but it also supports the kind of traceability Western buyers increasingly demand.

Still, big hurdles remain. Eastern Congo’s insecurity is not a side issue, it’s the operating environment. Analysts have noted that U.S. diplomacy in the region has increasingly linked peace efforts with mineral access and corridor development, betting that economic incentives and logistics upgrades can stabilize supply chains and reduce the leverage of armed actors. But persistent violence and governance risks could complicate any investment timetable, even if headline agreements are signed.

In Africa-wide terms, the US-DRC minerals track is also part of a broader “new scramble” for clean-energy inputs, one increasingly packaged as partnership but widely debated as transactional. The Lobito Corridor, backed by the U.S., EU, and development banks, is a concrete example: it aims to move copper and cobalt more efficiently from the Central African interior to global markets via Angola’s Atlantic port, reducing transit times and costs and offering an alternative to routes tied to competing geopolitical blocs.

What comes next is likely to be less about announcements and more about execution: final investment approvals, bankable offtake terms, stronger traceability, and credible community benefits near mining zones. If the pieces land, the US-DRC critical minerals deal could reshape how Congolese metals reach Western factories, while setting a template for how security, infrastructure, and resource diplomacy are stitched together across Africa’s mineral belt.