In an era once defined by globalization and open markets, the world economy is now witnessing a dramatic reversal. A new wave of protectionism manifested through tariffs, trade barriers, subsidies, and localization mandates is redrawing the map of global commerce. Once hailed as the driver of shared prosperity, globalization is facing its most serious challenge yet, as nations increasingly turn inward to safeguard their industries and assert economic sovereignty.

The modern phase of protectionism can be traced back to the U.S.–China trade war that erupted in 2018, when both nations imposed sweeping tariffs on hundreds of billions of dollars’ worth of goods. That confrontation, initially seen as a bilateral dispute, soon rippled through global supply chains, forcing multinational companies to rethink production and sourcing strategies. The situation worsened during the COVID-19 pandemic, when border closures and medical supply shortages exposed the fragility of global interdependence. The Russia–Ukraine conflict further underscored the vulnerability of energy and food systems, prompting countries to prioritize self-reliance and security. By 2025, protectionism has become a defining feature not only in the United States and China but also across the European Union, India, Japan, Brazil, and other emerging economies, each reshaping trade rules to favor domestic priorities.

At its core, protectionism refers to government measures that restrict international trade in order to protect local industries from foreign competition. Traditionally, these measures include tariffs, import quotas, and subsidies. However, the new frontiers of trade wars go beyond conventional tools. Today’s protectionism extends into digital, technological, and environmental domains, intertwining economics with geopolitics. For example, the U.S. CHIPS and Science Act encourages domestic semiconductor manufacturing to reduce dependence on Asian suppliers, while the European Union’s Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) effectively taxes imports from countries with looser environmental regulations. These policies are framed as necessary for national security or climate action, but their cumulative effect is the fragmentation of the global trading system.

Several factors are driving this renewed protectionist surge. Rising national security concerns have made countries wary of relying on foreign suppliers for critical goods like chips, pharmaceuticals, and rare earth minerals. Economic nationalism, fueled by political populism and discontent over job losses, has pressured governments to “bring industries home.” Meanwhile, geopolitical rivalries, particularly between the United States, China, and Russia, have made trade a tool of strategic influence rather than cooperation. The post-pandemic supply chain shocks exposed overdependence on single sources, spurring “reshoring” and “friendshoring” strategies. Furthermore, the global climate transition has introduced a new layer of economic competition, as nations use green subsidies and carbon tariffs to favor local industries.

The global impact of this protectionist wave is profound and multifaceted. Developing economies, especially export-dependent ones in Asia, Africa, and Latin America, face shrinking market access as advanced economies prioritize local manufacturing. Consumers worldwide are feeling the pinch as prices for electronics, electric vehicles, and energy-related products rise due to tariffs and trade restrictions. Global corporations are restructuring supply chains, moving away from the once-dominant “China-centric” model toward regional production hubs. The World Trade Organization (WTO), once the guardian of free trade, is struggling to remain relevant as major economies bypass its rules through bilateral and regional agreements. In the technological realm, the world is increasingly splintered into competing ecosystems, with the U.S. and China leading separate networks in artificial intelligence, semiconductors, and telecommunications.

Recent examples illustrate how widespread this trend has become. The U.S.–China tech war continues to intensify, with export bans on advanced chips and restrictions on Chinese tech giants. The European Union’s CBAM introduces tariffs based on carbon emissions, effectively penalizing imports from developing nations. India’s “Make in India” initiative imposes higher duties on electronics and solar equipment to encourage domestic manufacturing, while Brazil has raised agricultural tariffs to shield its farmers. Japan, on the other hand, has moved to secure rare earth supplies, imposing export restrictions and stockpiling resources essential for its industries.

According to International Monetary Fund (IMF) projections, sustained protectionist measures could reduce global GDP growth by up to 1.5% annually if trade barriers persist. Yet advocates argue that “strategic protectionism” can foster innovation, protect jobs, and build resilience against global shocks. The real challenge lies in balancing these competing priorities, preserving economic sovereignty without triggering a spiral of retaliation and isolation.

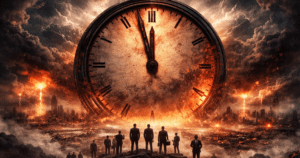

Looking ahead, economists foresee a fragmented form of globalization rather than its demise. The world may reorganize into regional trading blocs- the Americas, Europe–Africa, and Asia–Pacific; each building semi-autonomous supply networks. In this emerging order, competition will center on cutting-edge technologies such as artificial intelligence, green hydrogen, and defense systems. As nations navigate this delicate balance between cooperation and confrontation, one truth is clear: the trade wars of the future will not be fought with weapons, but with tariffs, data, and carbon taxes.