Throughout the annals of maritime history, the spectre of piracy has haunted merchant shipping lanes, testing the ingenuity and resolve of seafarers and naval strategists alike. From the swashbuckling marauders of the so-called Golden Age of Piracy to the missile-armed insurgents of today’s volatile maritime theatres, the nature of the threat may have changed, but its essence remains rooted in the disruption of commerce, the assertion of power, and the exploitation of vulnerable shipping routes.

Historical Echoes: The Age of Pirates and Imperial Responses

The 17th and 18th centuries were the apex of piracy in the Caribbean and the Atlantic. Figures such as Edward Teach, known to the world as Blackbeard, became infamous not only for their brutality but also for their calculated use of psychological warfare. Blackbeard famously wove slow-burning fuses into his beard, creating an aura of demonic invincibility during boarding actions. His reign of terror culminated in 1718 off the coast of North Carolina, where he was killed in battle with British Royal Navy forces, following a deliberate campaign to root out piracy from the American colonies.

Bartholomew Roberts, often called the ‘Great Pirate Roberts,’ was another formidable figure—his career, lasting only three years, saw the capture of over 400 vessels, from the coasts of Africa to the Caribbean. His operational model was one of relentless aggression combined with strict internal discipline, demonstrating that successful piracy often required as much organisational acumen as bravado.

Meanwhile, Henry Every, sometimes styled as ‘The Arch Pirate,’ masterminded what remains one of the most profitable pirate heists in history—the 1695 capture of the Ganj-i-Sawai, a Mughal treasure ship laden with gold, silver, and jewels. His actions triggered diplomatic crises between Britain and the Mughal Empire, highlighting the international ramifications of piracy and forcing European powers to adopt more assertive maritime policies.

In response to these threats, imperial powers developed robust naval doctrines designed not merely to defend merchant vessels but to project national power on the high seas. The British Royal Navy pioneered the concept of permanent overseas squadrons, strategically stationed in key maritime chokepoints. The 1718 assault on Nassau in the Bahamas—known as the campaign that dismantled the self-proclaimed Republic of Pirates—is a textbook example of such offensive operations, where the aim was to deny pirates their safe havens entirely.

Similarly, Spain’s ‘flota’ system, operationalised from the 16th century, epitomised defensive convoy strategy. Treasure fleets from the Americas would sail under the protection of heavily armed galleons, forming tight, well-defended flotillas designed to repel pirate raids and privateer attacks. The success of this system helped Spain maintain its economic supremacy in Europe for over a century, proving the value of coordinated, state-sponsored maritime protection.

Modern Parallels: Houthis, the Red Sea, and the Return of Asymmetric Maritime Warfare

These historic precedents resonate powerfully in the 21st century, as global shipping lanes face a resurgence of asymmetric maritime threats—albeit without the Jolly Roger fluttering from the masthead. Since late 2023, Yemen’s Houthi rebels have waged an unprecedented campaign against commercial shipping in the Red Sea, Bab el-Mandeb Strait, and the Gulf of Aden, deploying an arsenal of ballistic and cruise missiles, sea drones, and remote-controlled explosive-laden boats.

While their motivations are rooted in regional politics and the Israel-Gaza conflict, the Houthis’ tactics mirror classic piracy in their disruption of trade routes and coercive diplomacy through violence at sea. Their attacks have forced major shipping lines to divert vessels thousands of miles around Africa’s Cape of Good Hope, triggering supply chain disruptions and raising global freight costs.

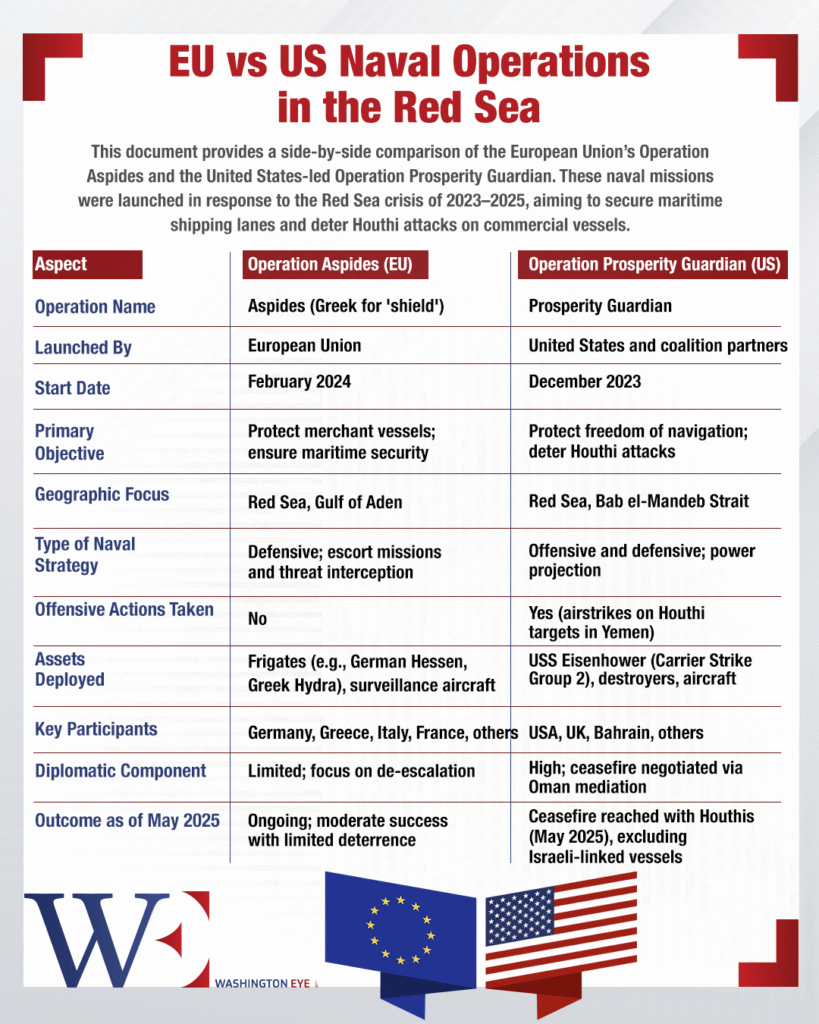

In response, the European Union launched Operation Aspides in early 2024, deploying a naval task force aimed at escorting vessels and deterring Houthi attacks. The operation, reminiscent of the Royal Navy’s convoy escorts during the Napoleonic Wars, prioritised defensive postures, with frigates and destroyers patrolling key lanes and providing air defence cover. However, as in the age of sail, purely defensive strategies showed their limitations—Houthis leveraged the speed, range, and ubiquity of modern missiles and drones, often overwhelming naval screens and striking at distances that outpaced traditional patrol tactics.

Operation Prosperity Guardian: Offensive Doctrine Reimagined

In contrast, the United States’ Operation Prosperity Guardian, initiated in 2024, embraced a more offensive posture, drawing clear parallels to Britain’s historical approach to piracy. Rather than merely protecting shipping lanes, the U.S. Navy and Air Force conducted precision strikes against Houthi missile launch sites, radar installations, and drone assembly workshops inside Yemen, aiming to degrade the group’s offensive capabilities at their source.

This approach harks back to the Royal Navy’s philosophy of taking the fight to the pirates’ doorstep—denying them the sanctuary from which to project power. The May 2025 ceasefire agreement brokered by Oman following these strikes reflects the effectiveness of such a strategy. Yet, the deal’s exclusion of Israeli-linked vessels underscores the fragility of these arrangements and the complex interplay of military action, diplomacy, and geopolitical bargaining that defines modern naval conflict.

Beyond the Horizon: Adapting Legacy Strategies to New Threats

The current Red Sea crisis is not an anomaly—it is part of an evolving pattern of maritime contestation, where non-state actors, backed by state sponsors, weaponise commercial vulnerabilities in critical chokepoints. From the Houthis to Somali pirates in the previous decade, the common thread is the exploitation of ungoverned maritime spaces, where global commerce remains most exposed.

In this environment, navies of the world—particularly those of the West—are once again confronted with the age-old challenge of protecting freedom of navigation, but in an era where the tools of disruption are faster, cheaper, and more accessible than ever before. The lessons of the past—whether the Spanish flota system, the British suppression campaigns against pirate strongholds, or even the coordinated multinational anti-piracy patrols off Somalia—are as relevant today as they were in the age of galleons and cutlasses.

But innovation must complement tradition. Modern navies must integrate cyber capabilities, space-based surveillance, and unmanned systems into their doctrines to remain effective in an increasingly congested and contested maritime domain. They must also foster international cooperation, recognising that the seas are not just a battlefield but the lifeblood of global commerce and stability.

From Blackbeard to ballistic missiles, the oceans have always tested the will and adaptability of those who sail them. The contest for maritime control is far from over, and the next chapter is being written not in the pages of history books, but in the shifting waters of the Red Sea, the South China Sea, and beyond.