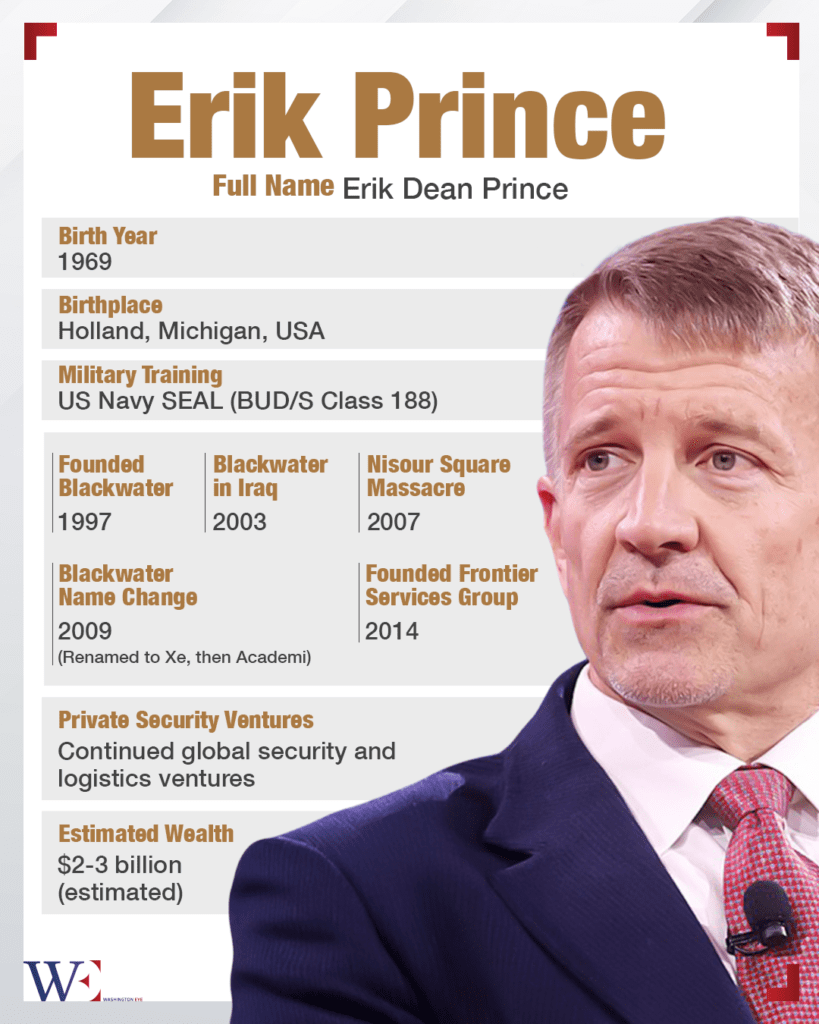

The role of private military contractors (PMCs) has historically been associated with war zones, security operations, and intelligence work. However, the latest reports indicating that Erik Prince, the founder of Blackwater, has proposed using PMCs for mass deportations of undocumented immigrants in the United States raises significant questions about the evolving role of these entities.

This proposal—reportedly considered by former President Donald Trump—suggests outsourcing immigration enforcement to private forces, a move that would mark a major shift in U.S. immigration policy.

But is this the first time private contractors have been used in such a role? A look at historical precedents suggests otherwise.

The Role of Private Military Contractors in History

PMCs have long been employed by states for functions that were traditionally handled by government forces. These companies are not merely mercenary outfits but are legally registered entities operating in various capacities worldwide, often at the behest of governments or corporations. The historical use of PMCs extends beyond combat and has included policing, border security, and other governmental functions.

1. The British East India Company (1600-1874): A Private Military in Colonial Administration

One of the earliest large-scale examples of private forces acting in a governmental capacity was the British East India Company. This corporation controlled vast territories and maintained a private army that at its peak outnumbered the British Army itself. The company played a role not just in military conquest but also in governance, law enforcement, and customs enforcement, effectively acting as a quasi-state entity. The use of private forces to control populations and enforce policies was a direct forerunner to modern PMCs being employed in unconventional roles.

2. The Pinkerton National Detective Agency (1850s-1930s): Private Enforcement in the U.S.

During the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the U.S. government and private businesses frequently employed the Pinkerton National Detective Agency to conduct security operations, strike-breaking, and surveillance. The agency was often used in roles that blurred the line between private and public law enforcement, including mass arrests and deportations of labor organizers and immigrant workers during times of unrest. This period demonstrated that private security forces could be used to control and manage populations in ways that were often legally dubious but politically expedient.

3. The French Foreign Legion and Mercenary Forces in Africa (1950s-1970s)

Although not a private company, the French Foreign Legion functioned in ways similar to modern PMCs, enforcing colonial rule and stabilizing regions to serve French geopolitical interests. Private mercenary outfits such as those led by Bob Denard and Jean Schramme operated extensively in Africa, conducting government-backed deportations, forced relocations, and population control in former colonies such as the Democratic Republic of Congo and Angola. These mercenaries often acted as de facto immigration enforcement agents, removing or displacing populations deemed a threat to European interests.

4. South Africa’s Executive Outcomes (1990s): Private Armies in Conflict and Security Roles

One of the most well-known PMCs of the modern era, Executive Outcomes, operated in Angola and Sierra Leone, stabilizing governments and enforcing order in regions affected by civil war. Though primarily involved in combat operations, PMCs like Executive Outcomes have also been contracted for border security and law enforcement roles, demonstrating the willingness of governments to privatize functions related to population control.

5. Blackwater’s Role in Iraq and Afghanistan (2000s): A Precedent for Expanding PMC Authority

Erik Prince’s Blackwater became infamous for its operations in Iraq, where it provided security for U.S. diplomats and carried out paramilitary operations. However, the company also played a role in detention, intelligence gathering, and border security, highlighting its ability to function in non-traditional military roles. This paved the way for considering PMCs for domestic enforcement functions, such as the recent proposal for deportation operations.

Has This Been Done Before?

While the specific use of PMCs for deportations in the U.S. would be unprecedented, historical precedents exist for using private forces in similar roles. Several examples illustrate how private entities have been involved in immigration control and population removals in various contexts:

- United States – GEO Group and CoreCivic: These companies operate private immigration detention centers under contracts with Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), playing a major role in detaining and processing undocumented immigrants. While they do not directly conduct deportations, their involvement demonstrates how immigration enforcement has already been partially privatized.

- Israel – Modi’in Ezrachi and Shahar Security: Private security firms have been contracted by the Israeli government to assist with border security, detaining individuals deemed security risks, and managing checkpoints in the West Bank.

- Australia – Serco: The Australian government contracts Serco to operate offshore immigration detention centers, handling detainee processing, security, and in some cases, deportation logistics.

- European Union – Frontex Private Contractors: The EU has worked with private security firms to monitor migration routes, assist in border security, and detain individuals before deportation, particularly in the Mediterranean and North African regions.

Potential Legal and Ethical Issues

The legal framework surrounding immigration enforcement in the United States mandates that only government agencies, such as ICE, have the authority to carry out deportations. If PMCs are contracted for this role, there could be significant legal challenges regarding their authority and oversight. The use of private contractors may allow the government to circumvent existing due process protections for undocumented immigrants, potentially leading to violations of U.S. and international human rights laws.

Accountability is another major concern. Unlike government agencies, PMCs operate with fewer transparency requirements. If abuses occur during deportations, holding these contractors accountable may prove difficult. Given Blackwater’s controversial history—including the 2007 Nisour Square massacre in Iraq—there are legitimate concerns that using private forces in immigration enforcement could lead to excessive force or human rights violations.

The use of force by private contractors is a significant risk. PMCs are typically trained for combat and security operations rather than immigration enforcement. Deploying personnel with military or paramilitary backgrounds to remove individuals from their homes or workplaces could result in violent confrontations, further fueling public outcry. Additionally, private contractors may not be bound by the same de-escalation policies that government immigration officers must follow.

From a political and public relations standpoint, outsourcing deportations to PMCs could provoke strong opposition both domestically and internationally. The optics of private forces conducting mass deportations—especially under a company with Blackwater’s reputation—would likely generate widespread criticism and legal challenges. Human rights organizations, advocacy groups, and even international allies of the United States may view such a move as a dangerous escalation of immigration enforcement tactics.

Finally, the economic implications of such a plan raise questions about government spending and cost-effectiveness. Hiring PMCs is expensive, and past contracts with private security firms have often been plagued by allegations of financial mismanagement and corruption. If deportation operations are outsourced, taxpayers could end up footing a significantly higher bill than if enforcement remained within government agencies.

Conclusion: A Dangerous Precedent?

The potential use of PMCs for deportations would represent a major expansion of their role, blurring the lines between military operations and domestic law enforcement. While this is not the first time private forces have been used to manage populations, it would mark a significant departure in U.S. policy. Given the historical precedents, it is clear that governments have turned to private entities for similar functions in the past—but the risks and controversies surrounding such actions remain significant.

Whether or not this proposal moves forward, it signals a broader shift toward the increasing privatization of government functions, raising questions about the future role of PMCs in domestic security and law enforcement.