War is on the horizon, and the United States is far from ready. The country’s naval power is atrophying. Its industrial capacity does not fare any better. China, the most powerful adversary of this century, continues to amass a larger maritime presence. The United States needs to expand its capacity for maritime force projection. To expedite this, some policymakers have advocated for employing a historic and long-disused method: letters of marque. Citing the Constitution’s explicit allowance of letters of marque, they argue that a privateer fleet can complement the U.S. Navy in the next war. This line of reasoning, while creative, fails to address the second-order ramifications of a resurgence in privateering. Privateering would erode the United States’ international leadership and accrue unresolvable costs, on balance damaging American maritime power. The naval services must retain a monopoly of violence in the maritime domain. As such, the U.S. government should not issue letters of marque to create a privateer fleet.

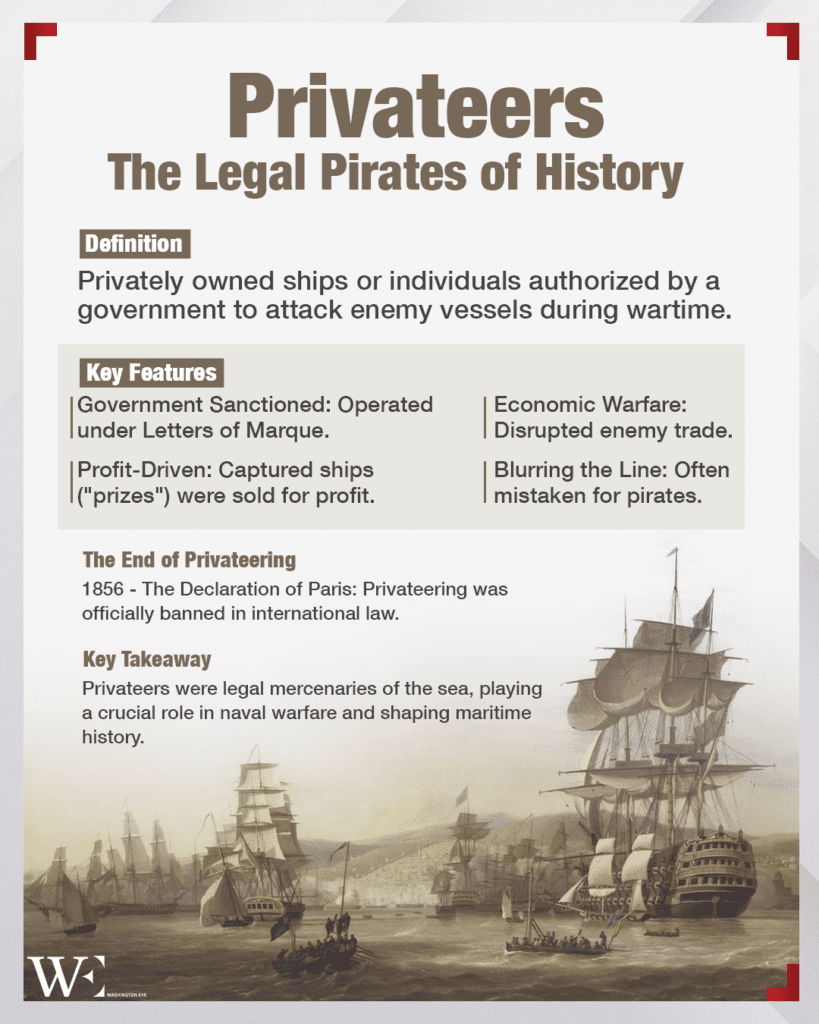

The American reconstitution of privateers would upend the infrastructure of international norms and damage the United States’ position of leadership in the international forum. First, the international community views the ban on letters of marque as customary international law. The Paris Declaration of 1856 states that privateering “is, and remains, abolished”. While the United States refused to sign the treaty, it has nevertheless abided by the provisions when at war since. Some argue that privateering can still be considered legal as the United States maintains its letter of marque constitutional clause and has not officially signed a treaty that dissolved the practice of issuing letters of marque. The general custom, however, remains that naval warfare and commerce raiding is the purview of commissioned warships, not warships-for-hire.

The legitimation of privateering would embolden the United States’ adversaries and exacerbate their malicious maritime activity. For example, China’s maritime militia harasses the fishing and commercial vessels of its neighbors within their Exclusive Economic Zones as well as on the high sea. The country also maintains its false claim of ownership over the South China Sea—a spurious claim denied by all of China’s maritime neighbors and contravened by international case law. The international maritime community recognizes that countries like China prefer to bully competitors rather than build partnerships. A resurrection of privateering would undo U.S. efforts to promote and enforce the rules-based order at sea. When a U.S. Naval Institute article advocated for the return of the U.S. privateer enterprise, a spokesman for the Chinese Ministry of Defense stated that such “criminal activities” would “receive joint opposition and a severe backlash from the international community.” If the United States issued letters of marque, China would likely treat any captured U.S. privateer as a pirate and sentence them accordingly. It may also feel emboldened to retaliate in kind or disregard other maritime customs that have more legal strength. The United States should abide by international custom to retain its moral authority and international support against Chinese malfeasance.

A resurgence of privateering risks the expansion of other illicit maritime activity. Privateering is akin to piracy, albeit sanctioned by a legal certificate. Like pirates, privateers hunt merchantmen for profit, even if they are more selective in their targets. Some privateers may espouse patriotic values. The chase and capture of the St. Lawrence during the War of 1812 is one such example. Most, though, privateer for the money. This is best displayed in some privateers’ career decisions after a war concludes. After the Queen Anne’s War, several privateers saw their profits evaporate. With commerce raiding as their only marketable skill, many, including Edward “Blackbeard” Teach, resorted to piracy. Piracy is one of the few universal crimes recognized by all nations. If privateer forces were to run rampant and devolve into piracy, it would severely damage the tenets of maritime governance and the United States’ leadership role in the maritime community. Washington should not reopen a profit stream with ties to maritime crime.

The efficacy of privateers in today’s maritime world is tenuous at best and could easily unravel in many scenarios. The task of a privateer is twofold: acquire enemy commerce, then bring it to a friendly port for a reward by a prize court. However, the prevalence of “flags of convenience” among the world’s merchant fleets could make it difficult for privateers to accomplish the former without incurring severe backlash from neutral nations. Concerning the second task, China could leverage its deep political and economic ties to Latin America and Africa to deny privateers the ability to enter ports. If this were coupled with a framing of American letters of marque as a scourge to the rules-based order, U.S. privateers would be severely limited in where they can deliver their prizes or refit their ships. This would allow China to better locate privateers’ positions, recover prizes or deny them to the enemy, and isolate the U.S.-led coalition from the international community. Also, if letters of marque are issued, China could employ its intelligence network to identify privateers, access their accounts and data, and exploit the data to pre-empt and counter privateer action. In December 2024, Chinese hackers accessed U.S. Treasury documents through a third-party software provider; China could repeat this ploy to the recipients of letters of marque, thwarting their abilities to procure and operate privateer enterprises. This can range from accessing their bank accounts to viral attacks on their servers. Then, the Chinese fleet, which continues to grow and hone its capabilities, could hunt the remaining ships down. The employment of privateers would require China to reallocate critical naval assets, invest substantial intelligence resources, and use political capital to eliminate the threat. But rather than providing a decisive advantage to the United States, the privateer affair would serve as a temporary distraction and enable China to strengthen its coalition and international presence.

The employment of privateers would create an undue administrative burden on the United States as it seeks to wage war. The United States cannot simply hand out certificates and let newly minted privateers operate on the high seas. Privateers would act with the consent of the United States and thus be maritime representatives. The United States would require an immense bureaucracy to regulate the privateer fleet. This would include establishing a set of rules to distinguish privateering from piracy. The Navy Department would have to hire clerks, inspectors, and regulators to ensure its privateer fleet acts within the scope of the laws of war. A demand for a privateer fleet would distract the U.S. defense industrial base from expanding and supplying the U.S. Navy; during the American Revolution, Commodore Esek Hopkins had faced the impacts of a demand for privateers, complaining that he could not procure supplies and—more importantly—professional sailors to form a strong Continental Navy. The judicial system would also need to adapt, as admiralty courts would expand to adjudicate prize law. Some argue that present program and management issues in the Department of Defense stunt the military’s ability to acquire materiel and generate waste. A privateer system would exacerbate these administrative issues and add unnecessary complexity to the execution of war.

Commerce denial remains an important aspect of naval warfare; those with large navies will tend to blockade and convoy, while those with a smaller naval presence will likely authorize commerce raiding. Despite the unsuitability of privateers in today’s fleet, the United States must still maximize its capability to deny enemy commerce and destabilize the adversary’s capabilities. To do this, the United States must increase the size of its warship, submarine, and commercial fleet. This will require a shift in funding to prioritize naval buildup, which may stall other projects. It must also continue to recruit Sailors, Coast Guardsmen, and Merchant Mariners. With proper warships and manning, the naval services can fight the enemy and execute the privateer’s mission: stunt the enemy’s maritime economy.

The best path to denying enemy commerce is isolating the adversary from the rest of the world. To that end, a coalition-led blockade and port denial of enemy-flagged and aligned ships could rapidly destabilize an adversary’s merchant fleet. It would be difficult to form and maintain such a coalition if the United States engaged in a controversial practice like privateering.

A functioning economy and uninterrupted income are critical factors in maintaining a war effort. In a major war with an adversary, the United States must be able to preserve its own merchant marine while constraining or destroying its enemy’s commercial fleet. When the next war comes, the United States needs to produce a strong naval force and possess a strong coalition. The resurrection of privateers from the graveyard of maritime history will accomplish neither.

The views expressed in this piece are the sole opinions of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the Center for Maritime Strategy, the United States Coast Guard, the Eighth Coast Guard District, or other institutions listed.

Republished with Permission from the Center for Maritime Strategy