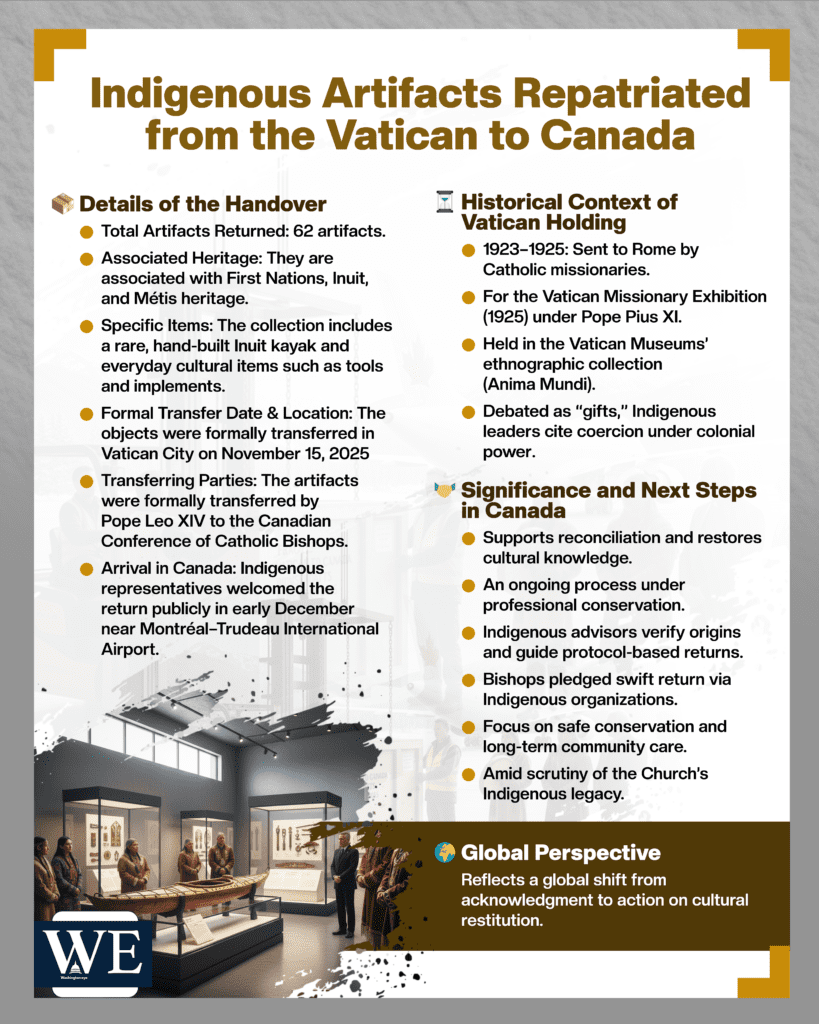

The Vatican has returned a collection of Indigenous cultural objects to Canada in a repatriation move that Indigenous leaders and Canadian officials are framing as a concrete step toward reconciliation, while also renewing debate over how “voluntary” many colonial-era transfers to European institutions really were. The handover involved 62 artifacts associated with First Nations, Inuit and Métis heritage, including a rare, hand-built Inuit kayak and everyday cultural items such as tools and implements that carry deep community meaning beyond their museum value.

The objects were formally transferred by Pope Leo XIV to the Canadian Conference of Catholic Bishops (CCCB) in Vatican City on November 15, 2025, with the bishops committing to move them “as soon as possible” toward the communities of origin through National Indigenous organizations and community-led provenance work. In Canada, Indigenous representatives welcomed the return publicly in early December, when leaders gathered near Montréal–Trudeau International Airport to mark the artifacts’ arrival and emphasize that repatriation is not only about objects, but about restoring disrupted cultural transmission, how to build, use, name, teach, and ceremonially care for items that were separated from their makers and descendants for generations.

Media coverage from Canada described the moment as emotional and long-awaited, but also underscored that repatriation is a process, not a single event: the 62 pieces are being held first under professional conservation conditions while Inuit and other Indigenous advisors work with curators to confirm provenance and ensure the objects are returned in ways consistent with community protocols.

The Vatican’s explanation of how the items entered its holdings goes back roughly a century. According to reporting and church statements, the artifacts were sent to Rome by Catholic missionaries between 1923 and 1925 for the Vatican Missionary Exhibition of 1925, promoted during the pontificate of Pope Pius XI, and later folded into what is now the Vatican Museums’ ethnographic holdings (often associated in reporting with the Anima Mundi collection).

A key political and ethical tension sits here: Vatican and church sources have sometimes described the pieces as “gifts,” but Indigenous advocates and scholars argue that, under colonial power imbalances and church–state assimilation policies, “gift” language can blur coercion, dispossession, and the lack of meaningful consent. That debate is central to why the return matters: it is not merely a loan or a symbolic gesture, but an implicit acknowledgement that historical collection practices were entangled with unequal authority and cultural suppression.

The timing is inseparable from wider church, Indigenous politics in Canada. The repatriation comes in the wake of the Catholic Church’s heightened scrutiny over its role in Indigenous cultural loss and the legacy of residential schools, and follows high-profile reconciliation steps in recent years (including Vatican engagement with Indigenous delegations and public commitments to repair relationships). Canadian officials have publicly welcomed the return as supporting truth-and-reconciliation goals, while Indigenous leaders have framed it as a starting point that should expand, because many more items remain in overseas collections.

From an international heritage-governance perspective, the story also sits inside a broader global shift toward restitution and return. While not every repatriation is governed by a single binding “treaty” (especially for older transfers), UNESCO has long provided frameworks and diplomacy channels that encourage the return of cultural property and the resolution of restitution disputes, most notably through mechanisms designed to promote return and ethical cooperation between institutions and source communities. In practice, these frameworks reinforce norms around documentation, provenance, safeguarding, and negotiated settlement, exactly the issues now shaping what happens next with the 62 objects as advisors trace origins and plan community-appropriate care and access.

Quality and protection are a major part of the next phase: returned artifacts can be vulnerable to damage if rushed into unsuitable storage, so Canadian museum professionals and Indigenous partners are emphasizing conservation-grade handling, climate control, secure transport, and careful decisions about whether objects should be housed locally, rotated through cultural centers, or kept under specialized care while communities build infrastructure. Inuit representatives have also used the moment to highlight the need for resources so that repatriation does not become an unfunded mandate, because “bringing it home” must also mean having the capacity to protect it at home.

Ultimately, the Vatican’s return of 62 Indigenous artifacts is significant not only for what it restores, but for what it signals: that major global institutions are increasingly being pressed to move from acknowledgment to action, and that repatriation, done transparently, with provenance clarity and Indigenous authority at the center, can be both cultural repair and contemporary diplomacy. Still, as Indigenous leaders and some Catholic observers have pointed out, the work is incomplete: dozens returned is meaningful, but it also raises the question of how many more remain, and how quickly institutions will follow through when the spotlight moves on.