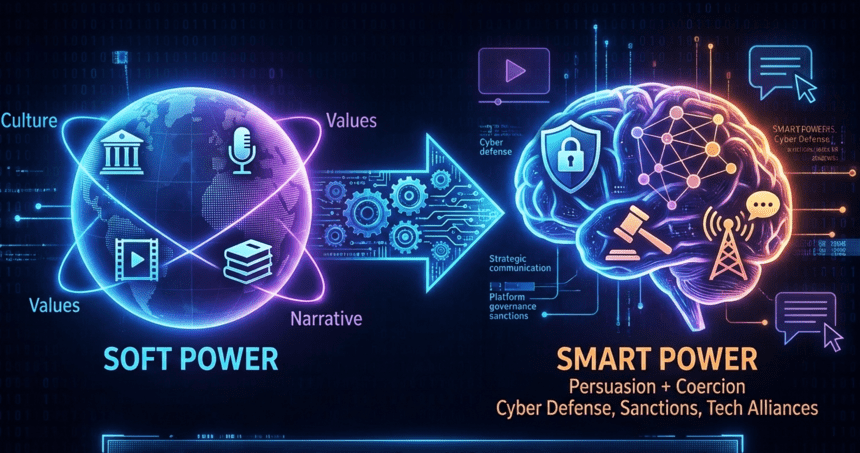

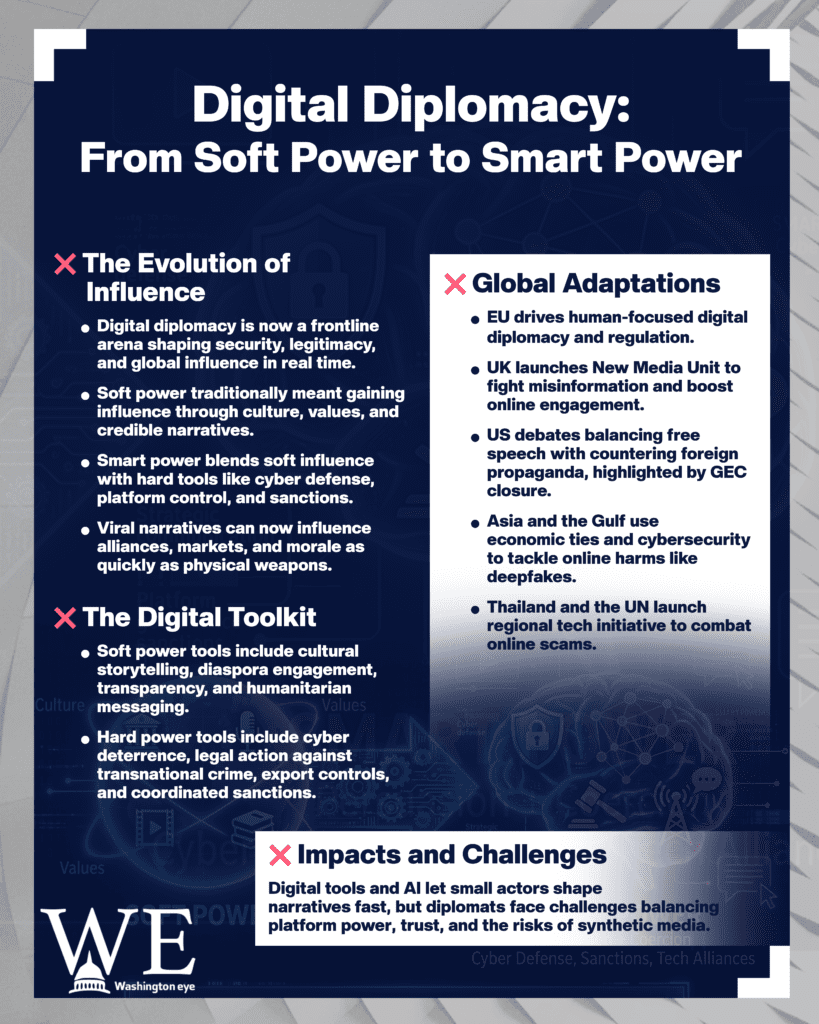

Digital diplomacy, the use of digital tools, platforms, and data to advance foreign policy has moved from being a “nice-to-have” public-relations layer to a core arena where influence, security, and legitimacy are fought over in real time. What used to be mostly soft power (attraction through culture, values, credibility, and narrative) is increasingly being fused with hard-edged capabilities, cyber defense, sanctions enforcement, platform governance, and counter-disinformation into what many policymakers describe as smart power: the strategic combination of persuasion and coercion, optimized for a fast, networked world.

This shift is happening “everywhere, all at once,” but the timing is not accidental. Over the last few years, states have learned that viral narratives can change alliances, markets, and battlefield morale almost as quickly as weapons move. Foreign ministries now run rapid-response digital teams, coordinate with tech platforms, and invest in monitoring influence operations. The European Union, for instance, frames “digital diplomacy” as a way to protect strategic interests while promoting a human-centric digital transformation, linking diplomacy directly to regulation, standards, and resilience. At the same time, the European Commission describes foreign information manipulation as a growing threat to democratic processes, amplified by new technologies that allow hostile actors to operate at unprecedented scale and speed, pushing governments to treat “information security” as part of national security.

The “where” of digital diplomacy is no longer just embassies and conference halls; it’s also TikTok feeds, encrypted messaging apps, livestreams during crises, and even the back-end infrastructure of digital identity and payments. The “when” is constant: a diplomatic signal can be sent at midnight, translated instantly, memefied by morning, and weaponized by noon. That’s why some governments are building new digital communications units not only to broadcast policy, but to compete in attention economies shaped by influencers, algorithms, and emotionally charged content. In the UK, a recent example of this trend is an overhaul of government media strategy, including a “New Media Unit,” explicitly designed to strengthen online engagement and counter misinformation dynamics.

“Smart power” in the digital era often looks like a blended toolkit. On the soft power side: cultural storytelling, diaspora engagement, public diplomacy campaigns, humanitarian messaging, and credibility-building through transparency. On the hard power side: cyber deterrence, legal action against transnational crime networks, export controls on sensitive technologies, and coordinated sanctions. In practice, governments are now forced to do both because influence operations, scams, and disinformation sit in the space between persuasion and coercion. A concrete illustration came this month in Bangkok, where Thailand’s foreign ministry and the UN Office on Drugs and Crime co-hosted a conference launching a multi-country initiative against online scams, with major platforms participating showing how diplomacy now directly intersects with tech companies, law enforcement, and cross-border digital threat response.

Countries are adapting at different speeds and with different philosophies. The EU emphasizes regulation, standards, and strategic communications as part of a broader digital governance model. The United States has debated where to draw lines between countering foreign propaganda and protecting domestic speech highlighted by the politically contested closure of the State Department’s Global Engagement Center (GEC), an office associated with counter-disinformation efforts. In Asia and the Gulf, digital diplomacy often blends economic statecraft, investment branding, “future city” narratives, AI partnerships with cybersecurity cooperation and crisis communications, especially as online harms (scams, influence operations, deepfakes) spill into real-world security and trust.

The impact is visible in at least four results. First, speed and reach: smaller states and non-state actors can punch above their weight by shaping narratives quickly, while major powers try to maintain message discipline across dozens of platforms. Second, platform power: diplomats increasingly negotiate not only with states, but with private companies whose moderation rules and recommendation systems affect what populations see. Third, the security–credibility dilemma: countering manipulation requires faster action and sometimes secrecy, but soft power depends on trust, openness, and consistent values, meaning heavy-handed tactics can backfire. Fourth, AI acceleration: AI tools can scale translation, content analysis, and consular services, but also scale deception, synthetic media, and micro-targeted propaganda raising ethical and governance questions for foreign ministries and publics alike.

Opinion among analysts is converging on one point: digital diplomacy is no longer just “communication,” it is capability. The smartest strategies treat digital outreach, cyber resilience, and information integrity as one integrated policy field because attraction without protection becomes fragile, and protection without legitimacy becomes unstable. The winners in the next phase won’t simply be the loudest online; they’ll be the actors that combine narrative credibility with institutional preparedness, turning soft power into smart power without losing the trust that made soft power work in the first place.