In a BBC Culture feature written by Nicholas Barber, the harrowing true story behind the infamous World War II breakout known as “The Great Escape” is revisited with fresh insight and firsthand testimony. Barber recounts how the operation, brought to life in the 1963 film of the same name, was in reality a meticulously planned, year-long effort involving covert tunnel construction, document forgery, and psychological endurance.

The Planning: Ambition in Captivity

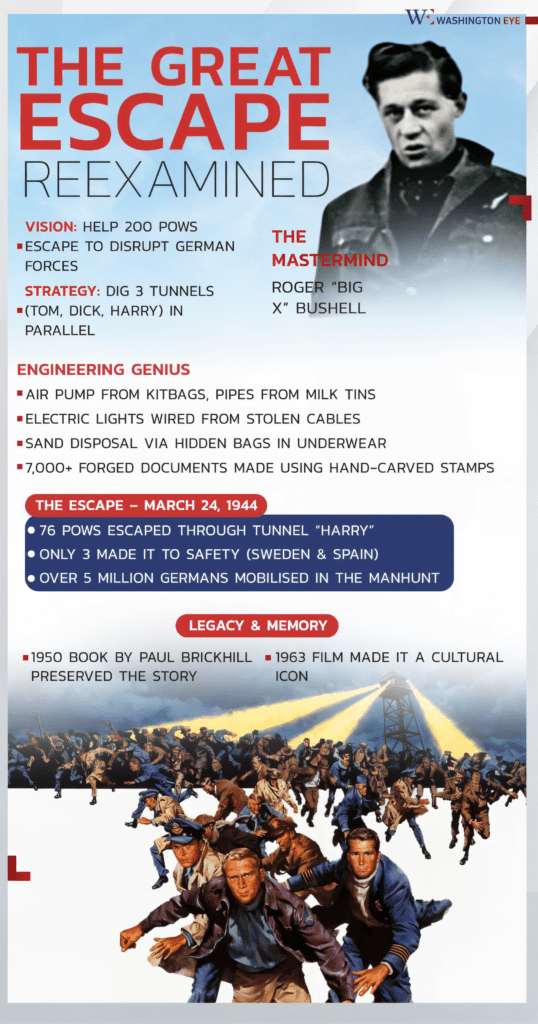

The escape was conceived more than a year prior, driven by Squadron Leader Roger Bushell, a veteran escape artist. Known as “Big X,” Bushell envisioned not just a breakout, but a strategic blow against German resources. His plan aimed to have 200 men escape, knowing it would force the Germans to divert massive personnel to track them down. He proposed digging three tunnels—Tom, Dick, and Harry—simultaneously. The logic was simple but brilliant: if the Germans discovered one, they might not suspect the others. The mere mention of the word “tunnel” was forbidden; Bushell even threatened court-martial for those who broke the code.

Even before the camp was built, prisoners had gained intelligence by volunteering to help with construction, allowing them to map out future escape routes. The site itself—Stalag Luft III—was chosen by the Germans specifically to deter escape. Built on yellow sandy subsoil that would reveal tunneling, surrounded by double barbed-wire fences and guard towers every 100 yards, and outfitted with buried microphones to detect sound, the camp was a fortress, yet the prisoners were determined.

Tunnel Engineering: Genius Under Pressure

Despite the camp’s defenses, the POWs’ ingenuity knew no bounds. Each tunnel required ventilation, lighting, structural support, and the safe disposal of soil. An air pump, cobbled together from kitbags and wood, supplied air via piping made from emptied Red Cross milk tins. Lights ran through cables stolen and repurposed from the camp’s systems. The real stroke of brilliance was in how the soil was discarded: prisoners fashioned “dispersal bags” out of long underwear, worn under their trousers. They would discreetly dump sand while walking in the yard, kicking it into the ground as they moved.

Forging documents was another monumental task. Ley Kenyon, one of the lead forgers, recounted how a printing press was created using hand-carved rubber letters—crafted from cobbler’s heels and bits of wood. The effort was extraordinary: between 7,000 and 8,000 counterfeit papers were created, ranging from identity cards to train tickets. A smuggled camera was used for photos, and bribes were used to gain access to real documents for replication. Every escapee needed civilian clothes, a backstory, travel papers, and a compass—each item a potential life-saver or a death sentence if it failed inspection.

The Escape: March 24, 1944

By winter 1943, tunnel “Harry” was completed and sealed, awaiting favorable conditions. On March 24, 1944, 220 men were selected. But the escape hit immediate snags. The tunnel came up short of the tree line, forcing escapees to crawl out in full view of guard towers. Additionally, the entrance trapdoor froze shut in the cold. Despite these obstacles, 76 men managed to crawl out before a guard spotted the 77th and raised the alarm.

The aim wasn’t merely freedom—it was disruption. The men understood that most would be recaptured, but hoped their efforts would scatter German resources. Paul Brickhill, who chronicled the events in his 1950 book The Great Escape, estimated that up to five million Germans were mobilized in the search. Ultimately, only three men evaded capture: two reached Sweden, and one made it to Spain.

The Tragic Aftermath: Hitler’s Retaliation

Enraged, Hitler initially ordered all 73 recaptured escapees executed. Though his advisors persuaded him to reduce the number, he still insisted that 50 be shot as a deterrent. This act—carried out deceitfully—was a clear violation of international law. Rather than being executed en masse as depicted in the film, the men were taken in small groups under the pretense of being returned to camp, then shot on isolated roadsides. Their remains were cremated, and the cause of death falsely attributed to escape attempts or resistance. As Foreign Secretary Anthony Eden later stated, the only explanation for cremation was to conceal the manner of death.

Among those killed was Roger Bushell. Shot in the back alongside his partner by the Gestapo, Bushell’s ashes were returned to camp, but his remains were lost during the chaos of advancing Allied troops. Survivors like Sydney Dowse and Jimmy James expressed disbelief that they weren’t executed themselves, calling their survival “just luck. And… pretty terrible”.

Justice and Historical Memory

The UK government was swift in its condemnation. Eden told Parliament in June 1944 that those responsible would be hunted down and brought to justice. Post-war investigations confirmed the planned executions, and 13 Gestapo officers were hanged for their roles. Yet the story could have faded without the work of Brickhill, whose book and its subsequent film adaptation kept the escape alive in public consciousness.

Survivor Charles Clarke, who had helped with the escape as a lookout, emphasized the importance of remembrance. “Without the film,” he said, “who would remember what a magnificent achievement it was?”.

A Final Note

Though the true story of the Great Escape is steeped in tragedy, it endures as a powerful testament to resilience, cooperation, and the unyielding pursuit of freedom. Through Nicholas Barber’s detailed recounting on BBC Culture, the operation emerges not as a romanticized caper, but as a stark reminder of the cost of war and the courage of those who resisted from behind barbed wire. The prisoners of Stalag Luft III were not just escapees—they were engineers, forgers, saboteurs, and survivors who turned captivity into quiet rebellion.