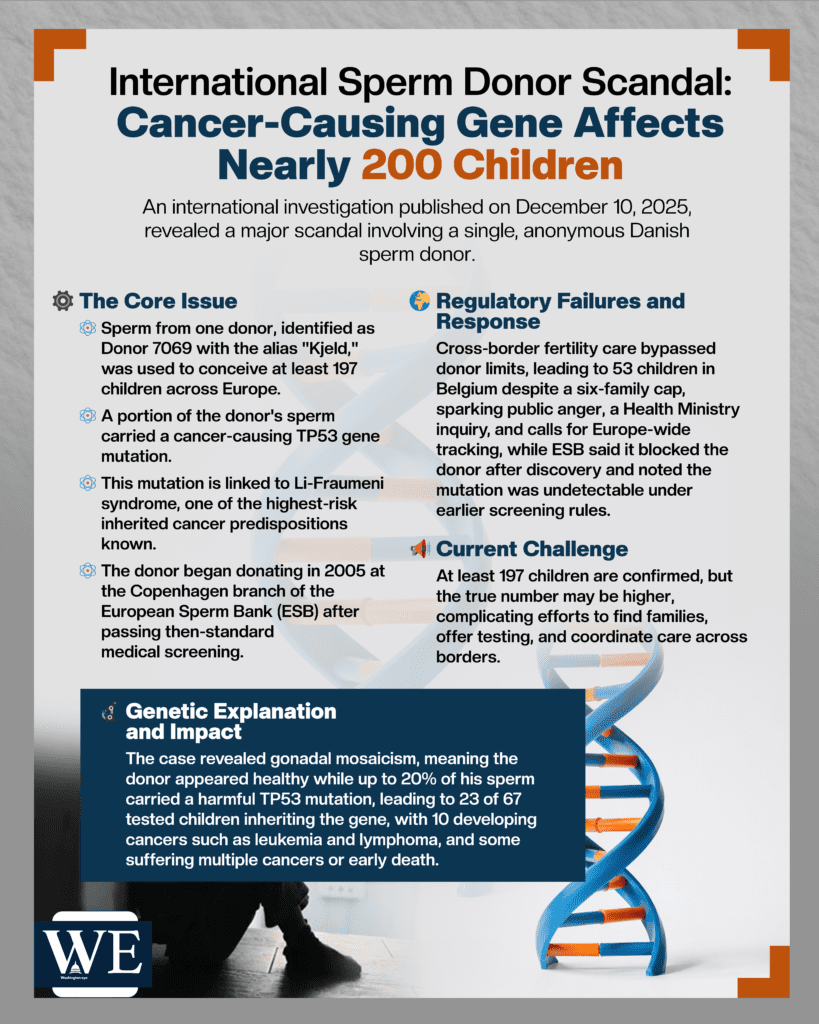

An international investigation published on 10 December 2025 has found that sperm from a single anonymous Danish donor, identified in reporting as Donor 7069 with the alias “Kjeld”, was used to conceive at least 197 children across Europe even though some countries cap the number of families or births per donor, and that a portion of the donor’s sperm carried a cancer-causing TP53 gene mutation linked to Li-Fraumeni syndrome, one of the highest-risk inherited cancer predispositions known.

The European Broadcasting Union (EBU) Investigative Journalism Network reported the donor began donating at the Copenhagen branch of European Sperm Bank (ESB) in 2005 after passing then-standard medical screening, and his sperm was distributed via 67 fertility clinics in 14 countries over roughly 17 years, creating a cross-border trail that regulators and clinics have struggled to fully trace. The central shock is that the harmful TP53 variant was not present in all of his sperm, investigators and clinicians described a scenario consistent with gonadal mosaicism, meaning the donor himself could appear healthy and pass routine checks while up to about 20% of sperm cells carried the mutation, leaving any child conceived with those sperm at risk of inheriting the variant in every cell of their body.

The case came to light after clinicians began noticing unusual and severe cancer patterns among donor-conceived children and raised alarms at the European Society of Human Genetics meeting; subsequent genetic testing and reporting found that among 67 children linked to the donor who were tested across multiple countries, 23 carried the mutation and 10 of those had already been diagnosed with cancers such as leukemia and lymphoma, with reports indicating that some children developed multiple cancers and some died young.

Families described learning the news via unexpected calls from fertility clinics years after conception, one mother in Paris told investigators she immediately recognized a Belgian city on her phone display because it was tied to her insemination trip long ago, and she was informed her child conceived in 2011 could have inherited a potentially deadly mutation, prompting urgent genetic counseling decisions and new fears over symptoms that might otherwise have been dismissed.

The investigation also scrutinized how donor-limits can be undermined by cross-border fertility care and inconsistent reporting between clinics and sperm banks: in Belgium, where sperm from one donor is supposed to be used by a maximum of six families, investigators reported 53 children were born to 38 women using this donor’s sperm, figures that have fueled public anger and renewed demands for a Europe-wide tracking and enforcement mechanism, not just national rules.

In Belgium, the revelations triggered a Ministry of Health inquiry that, according to the EBU investigation, uncovered additional instances of Danish donors being blocked in recent years due to hereditary-disease risks, adding pressure on regulators to tighten oversight of fertility medicine and gamete import systems. ESB has said it blocked the donor once the mutation was discovered and has expressed sympathy to affected families, while also arguing the variant could not reasonably have been detected under the screening standards in place at the time, an argument that has split reactions between those who see the episode as a tragic, extremely rare genetic event and those who see it as evidence the industry expanded internationally faster than safeguards, registries, and accountability.

Cancer-genetics specialists quoted in the reporting emphasized the lifelong burden of surveillance for carriers, often involving early, repeated screening and difficult family conversations, while patient advocates and some clinicians called for lower donor-offspring caps internationally, better real-time reporting from clinics to sperm banks, and clearer obligations to notify families quickly when serious genetic risks are identified.

Crucially, investigators stressed that “at least 197” is a minimum confirmed through public records requests and national authority responses, and the true number of children conceived could be higher, especially where countries cited confidentiality barriers or did not respond to information requests, meaning the public-health challenge now is not only preventing recurrence, but also locating families, offering testing, and coordinating care across borders in a system that was never designed for rapid, multinational recall-style alerts.