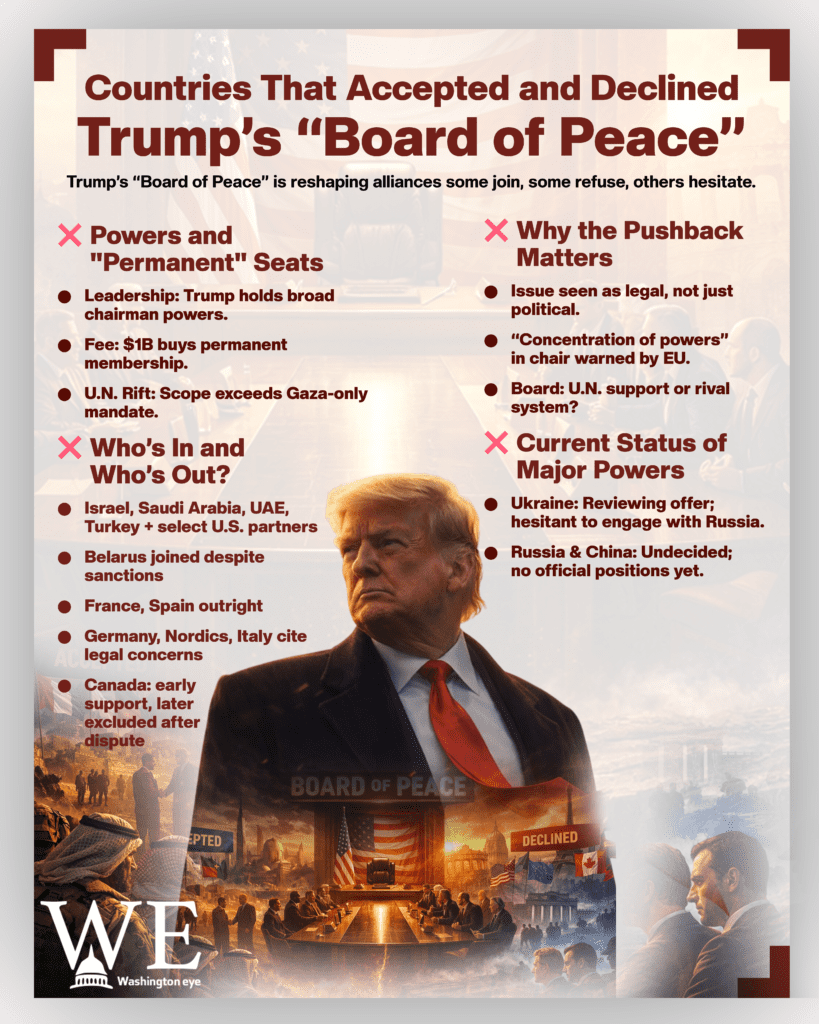

A new U.S.-backed diplomatic initiative dubbed the “Board of Peace” has begun to split U.S. allies and partners into clear camps: those who have accepted President Donald Trump’s invitation, those who have declined (or rejected it in its current form), and a third group that is stalling or studying the offer as questions mount over the board’s legality, governance and relationship with the United Nations.

What is Trump’s “Board of Peace” and why now?

According to a draft charter described by Reuters, Trump first floated the Board of Peace in September 2025 alongside a plan focused on ending the Gaza war, later signalling the remit could expand to other conflicts, including Ukraine. The charter envisions Trump as inaugural chairman with unusually broad executive powers, and it introduces a controversial structure: members serve three-year terms unless they pay $1 billion for “permanent” membership to fund the board’s activities.

Reuters also reported the U.N. Security Council mandated the board in November 2025, but only through 2027 and solely focused on Gaza, including authority tied to reconstruction coordination and a possible temporary stabilization force, with regular reporting to the Security Council. Critics argue the board’s newly widened scope goes beyond that U.N. framing.

Who accepted, who declined, who is hedging?

A senior White House official told Reuters that about 35 leaders had committed out of roughly 50 invitations. The “yes” list is anchored in parts of the Middle East and a set of U.S. partners elsewhere, while resistance has been strongest among several European governments citing constitutional or U.N.-charter concerns.

Germany’s Chancellor Friedrich Merz said Berlin supports peace efforts but cannot accept the plan “in its current form” due to constitutional concerns about the board’s governance structures, while remaining open to alternative formats with Washington.

An internal EU foreign-policy document cited by Reuters raised alarms about a “concentration of powers” in the chairmanship and warned of incompatibilities with EU legal principles; it also notes that France and Spain have declined. Spain’s Prime Minister Pedro Sánchez publicly said Spain would not join.

In North America, Canada’s position became politically tangled after Ottawa said it agreed “in principle” pending details, and then Trump withdrew an invitation to Canadian Prime Minister Mark Carney, following public sparring.

Countries That Accepted or Declined Trump’s “Board of Peace”

| Accepted | |

|---|---|

| Country | Reason / Official Position |

| Israel | Joined as part of U.S.-backed peace and security coordination |

| Saudi Arabia | Supports regional stabilization framework |

| United Arab Emirates | Backed initiative as alternative peace mechanism |

| Bahrain | Aligned with U.S. Middle East policy |

| Jordan | Sees role in Gaza stabilization and mediation |

| Qatar | Involved due to mediation role in Gaza |

| Egypt | Supports reconstruction and ceasefire oversight |

| Turkey | Joined despite NATO divisions |

| Hungary | Supported initiative despite EU criticism |

| Morocco | Backed U.S. diplomatic approach |

| Pakistan | Listed among supporting states |

| Indonesia | Joined as part of Global South representation |

| Kosovo | Backed U.S. leadership on peace initiatives |

| Uzbekistan | Participated in multilateral peace platform |

| Kazakhstan | Joined for regional diplomacy role |

| Paraguay | Supported U.S.-led peace effort |

| Vietnam | Joined as neutral international acto |

| Armenia | Participated for conflict mediation exposure |

| Azerbaijan | Joined amid regional diplomacy efforts |

| Belarus | Controversial inclusion due to Western sanctions |

| Declined | |

|---|---|

| Country | Reason / Official Position |

| Norway- Declined (current form) | Said plan conflicts with international law principles |

| Sweden- Declined (current form) | Objected to governance and legal structure |

| France- Declined | Raised concerns over concentration of power |

| Spain- Declined | PM said Spain would not participate |

| Germany- Declined (current form) | Cited constitutional and legal concerns |

| Italy- Declined (current form) | Legal incompatibility under Italian constitution |

| Canada- Pending / Withdrawn | Initially open, invitation later withdrawn by Trump |

| Ukraine- Reviewing | Expressed concern about sitting with Russia |

| Russia- Undecided | No official position announced |

| China- Undecided | Has not confirmed participation |

Why the pushback matters

Europe’s resistance is not just political symbolism: it goes to the heart of constitutional limits, who holds authority, and whether the board is an auxiliary, a rival, or a workaround to the U.N. system. The EU document described by Reuters argues the chair’s powers and participation controls clash with EU legal principles, and several governments have framed their “no” as a structural objection rather than opposition to peace efforts themselves.