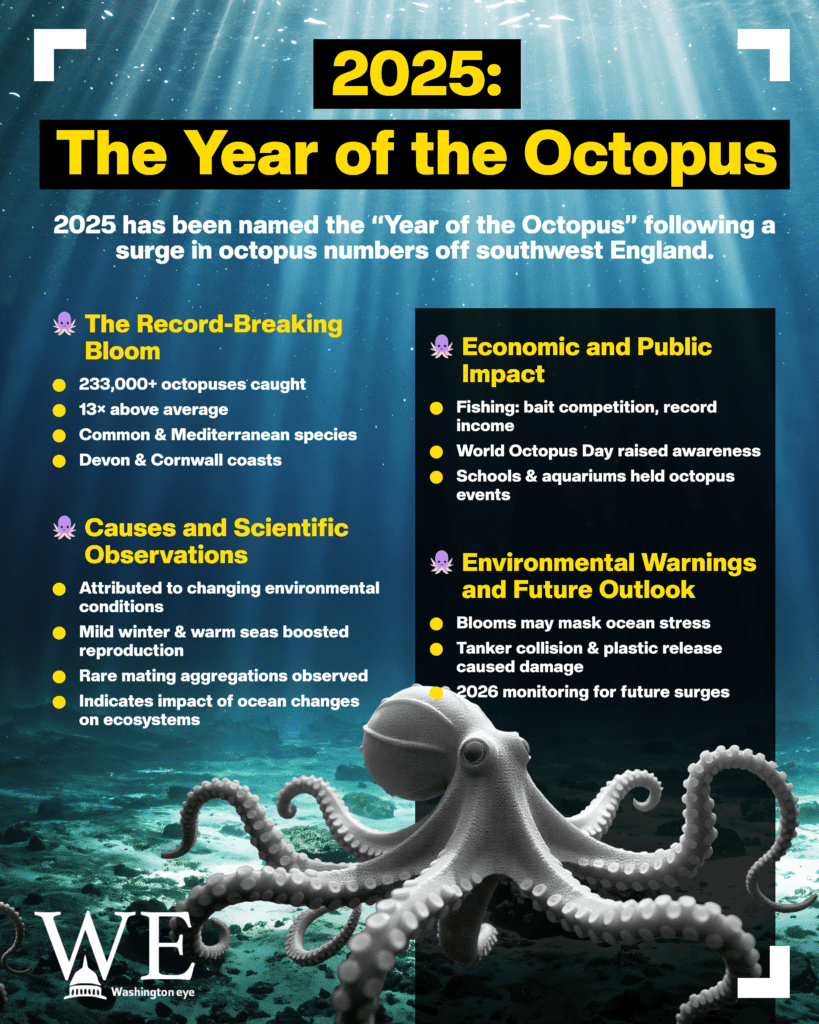

In a remarkable turn of marine ecological events, 2025 has been widely celebrated and officially described by conservation organisations as the “Year of the Octopus,” following an unprecedented surge in octopus sightings and population activity across the seas off the southwest coast of England. The declaration comes as scientists, fishers, and conservationists document the most significant bloom of common octopuses (Octopus vulgaris) in British waters since records began more than seven decades ago, transforming both scientific focus and public awareness of these enigmatic marine invertebrates.

The phenomenon, first noted in early spring and culminating through the year, saw record numbers of Mediterranean octopuses migrating into and thriving in coastal waters of Devon and Cornwall, where typically only modest numbers are found. Unusually warm sea surface temperatures after a mild winter created highly favourable conditions for octopus survival, reproduction, and juvenile development, according to local marine biologists tracking the bloom.

By mid-December, estimates from local fishery data and research surveys suggested catches exceeding 233,000 octopuses, roughly 13 times higher than the historical average, prompting conservation groups such as The Wildlife Trusts and Cornwall Wildlife Trust to designate the year as a momentous milestone for cephalopod populations and public engagement with marine life.

“This is not just a statistical anomaly, it’s a vivid indicator of how shifting ocean conditions influence marine ecosystems,” said Matt Slater, Marine Conservation Officer at the Cornwall Wildlife Trust. Slater noted that the octopus bloom offered rare opportunities to observe behaviours seldom seen in the wild, from mating aggregations in shallow waters to interactions with divers and underwater cameras.

The surge has also ripple effects on coastal livelihoods. Some local fishers initially expressed concern over changes in catch composition, reporting octopuses competing with lobsters, crabs, and scallops in trap lines. Yet others have found economic opportunity, with reports of record incomes from octopus landings during peak months. “It’s been a learning year for all of us, balancing traditional fishing with understanding these new dynamics,” said local skipper George Stevens.

Beyond England, scientists and conservationists around the world have pointed to 2025 as a year of heightened octopus awareness, in part because of World Octopus Day on 8 October, an annual date that celebrates the intelligence, adaptability, and ecological importance of octopuses. Observed internationally each year to raise consciousness about cephalopod biology and conservation needs, the day helped catalyse global attention toward octopus science and environmental threats such as habitat degradation and pollution. Researchers emphasise that cephalopods, despite not being classed as endangered, face mounting pressures from overfishing, pollution, and climate change, even as their populations show bursts of growth in certain regions.

The “Year of the Octopus” label has also stoked interest among marine educators, aquariums, and public science communicators, who organised events, exhibitions, and educational programs throughout the year. Schools hosted octopus-themed science days; aquaria offered live demonstrations explaining octopus intelligence and problem-solving capacities; and researchers shared insights into the unique neurobiology and camouflage strategies that make octopuses one of the ocean’s most fascinating taxa.

Nevertheless, the year was not without environmental concerns. Alongside the cephalopod boom, the UK’s seas experienced other stressors, including a major tanker collision in the North Sea and an accidental release of plastic biobeads off the Sussex coast, reminding stakeholders that marine ecosystems remain vulnerable even amid stories of ecological abundance. Conservationists warned that such population blooms can mask deeper systemic stress in ocean environments and called for continued investment in habitat protection, climate action, and sustainable fisheries management.

Looking forward to 2026, scientists are monitoring sea temperature trends closely to assess whether another octopus bloom might occur. Preliminary models suggest that if milder winters and warmer springs continue, similar surges could happen again, offering both research opportunities and conservation challenges. As one marine scientist noted, “The octopus doesn’t just thrive, it teaches us about resilience and complexity in nature.”

In marine biology circles, 2025 will be remembered not only for its octopus spectacle, but for the way it galvanized public fascination with one of the ocean’s most intelligent and mysterious creatures, ushering in a new chapter of cephalopod science, awareness, and stewardship.