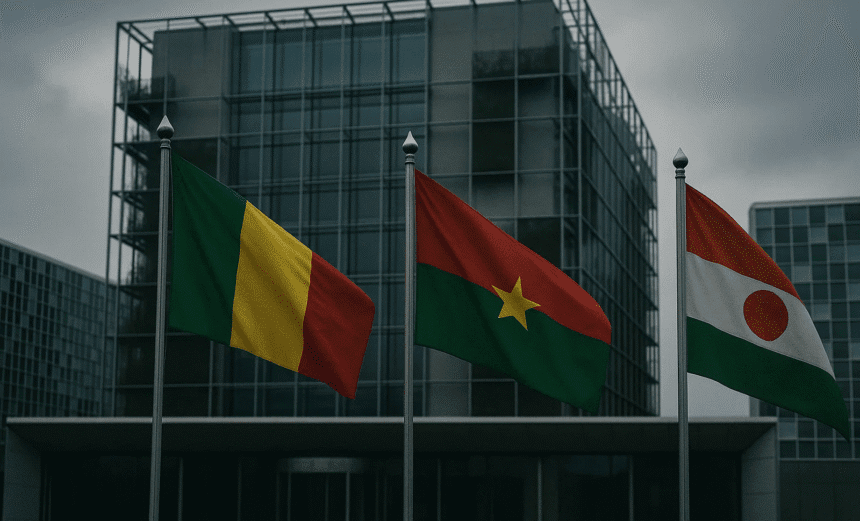

In a dramatic move signaling their continued break with Western-aligned institutions, Mali, Burkina Faso, and Niger have jointly announced their withdrawal from the International Criminal Court (ICC). The coordinated declaration was made on September 22–23, 2025, through government statements issued in Bamako, Ouagadougou, and Niamey. According to the Rome Statute that established the ICC, the withdrawal will only take effect one year after the countries formally notify the United Nations Secretary-General, but the announcement itself has already stirred strong reactions across Africa and beyond.

The military-led governments of the three Sahel states justified their decision by denouncing the ICC as “an instrument of neocolonial repression” that they believe applies justice selectively. In their joint statement, the leaders claimed that the court had proven “incapable” of delivering fair prosecutions for genocide, war crimes, crimes against humanity, or crimes of aggression. Instead, they argued that their nations should turn toward “indigenous mechanisms for peace and justice,” insisting that true sovereignty requires freedom from what they perceive as biased international structures. The statement did not highlight specific failings of the court, but the rhetoric closely mirrors earlier critiques from other African leaders who have long accused the ICC of disproportionately targeting the continent.

This decision is part of a wider strategy by the three countries, all of which are governed by juntas that seized power in recent years. Since coming to power, the military rulers of Mali, Burkina Faso, and Niger have steadily distanced themselves from regional and international organizations perceived as too closely tied to Western influence. Earlier in 2024, the trio withdrew from the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), citing its sanctions and political pressure, and they subsequently created the Alliance of Sahel States (AES) as a new regional bloc. The ICC withdrawal thus fits into a pattern of rejecting established international frameworks in favor of new alliances, often backed by alternative partners such as Russia.

The implications of this move are complex and far-reaching. Legally, the Rome Statute specifies that withdrawal does not exempt a state from obligations incurred while it was a party. That means that ongoing ICC investigations, particularly in Mali, where the court has been examining alleged war crimes since 2013, will not be automatically canceled. Crimes committed before the effective date of withdrawal can still fall under ICC jurisdiction. However, once the withdrawal takes effect in late 2026, citizens of these countries will no longer be able to turn to the ICC as a “court of last resort” if their own national systems fail to deliver justice. For victims of atrocities in conflict-torn Sahel, that could represent a profound loss of recourse.

International human rights groups have responded with alarm. Amnesty International described the withdrawal as “a serious backwards step in the fight against impunity,” stressing that it could deny victims the possibility of accountability for grave crimes. Human Rights Watch warned that the decision “endangers civilians,” given the widespread reports of abuses committed both by state security forces and by insurgent groups in the region. Critics argue that national judicial systems in Mali, Burkina Faso, and Niger are already under-resourced and subject to political pressure, making it highly unlikely that they can adequately replace the ICC in prosecuting complex atrocity cases.

Reactions from international institutions remain cautious. The ICC itself has not yet issued a detailed response, though legal experts note that the court has weathered withdrawals before, such as Burundi’s exit in 2017. Other member states may use the Assembly of States Parties to urge the Sahel trio to reconsider, highlighting the importance of global accountability in a region where violence and impunity remain acute. At the continental level, the African Union faces a delicate balancing act: while some African governments have echoed criticisms of the ICC in the past, others see membership as a vital safeguard against unchecked abuses.

Within the region, the political symbolism of the withdrawal may resonate with supporters of the junta, who frame the move as an assertion of sovereignty and resistance against foreign dominance. Yet for victims of mass violence, communities displaced by jihadist insurgencies, survivors of massacres, and families of those disappeared in military crackdowns, the withdrawal raises fears that their suffering may go unacknowledged in the absence of an impartial international court.

The announcement also deepens the geopolitical realignment underway in the Sahel. As ties with France, the European Union, and ECOWAS continue to fray, Mali, Burkina Faso, and Niger have sought closer security and economic cooperation with Russia and other non-Western partners. These partners, themselves outside the ICC framework, provide little incentive for the Sahel governments to remain engaged with the court. The ICC withdrawal, therefore, symbolizes not only a legal decision but also a political statement about where these countries see their future alliances.

Looking ahead, the path is uncertain. The one-year waiting period built into the Rome Statute means that there is still time for dialogue, persuasion, or potential reconsideration, though few expect the juntas to reverse course. The ICC will likely continue its ongoing cases, but its ability to enforce cooperation without the consent of the governments will be significantly weakened. Meanwhile, the Alliance of Sahel States may attempt to propose its own justice mechanisms, though observers doubt whether these will meet international standards of independence or effectiveness.

Ultimately, the withdrawal of Mali, Burkina Faso, and Niger from the ICC underscores the enduring tension between sovereignty and accountability in international law. It raises difficult questions about how the global community can ensure justice for victims of atrocities when national governments reject the very institutions designed to provide it. Whether this marks a temporary setback or a more permanent shift away from international justice in the Sahel will become clearer in the coming years, but for now, the decision represents a blow to the global fight against impunity.