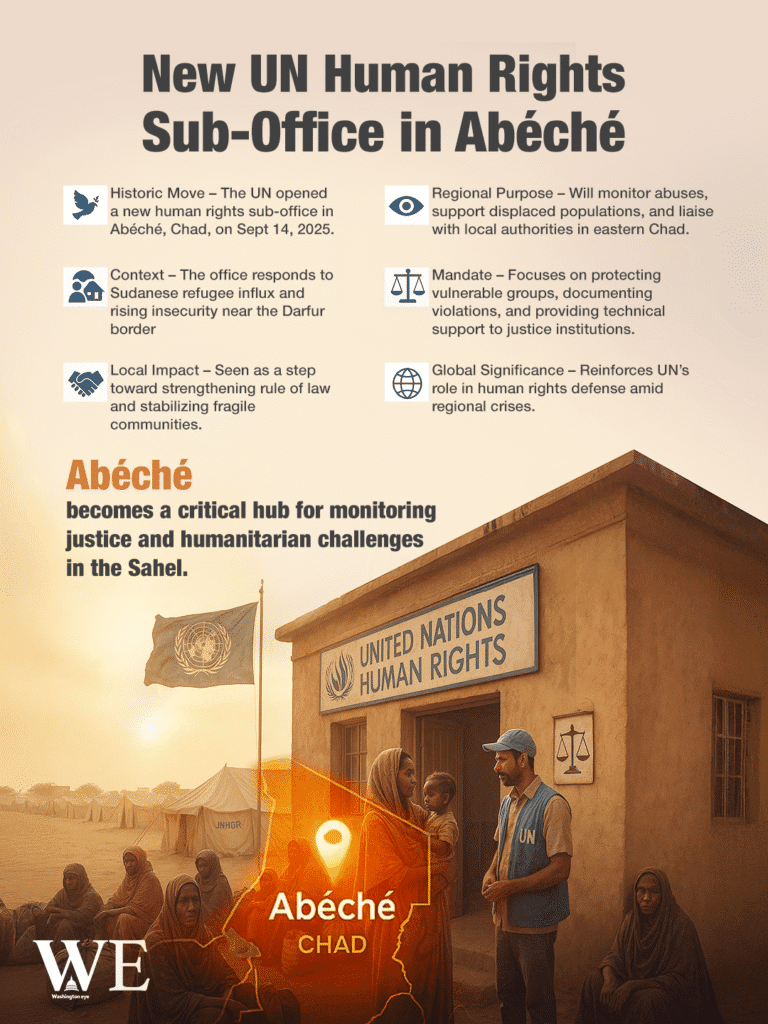

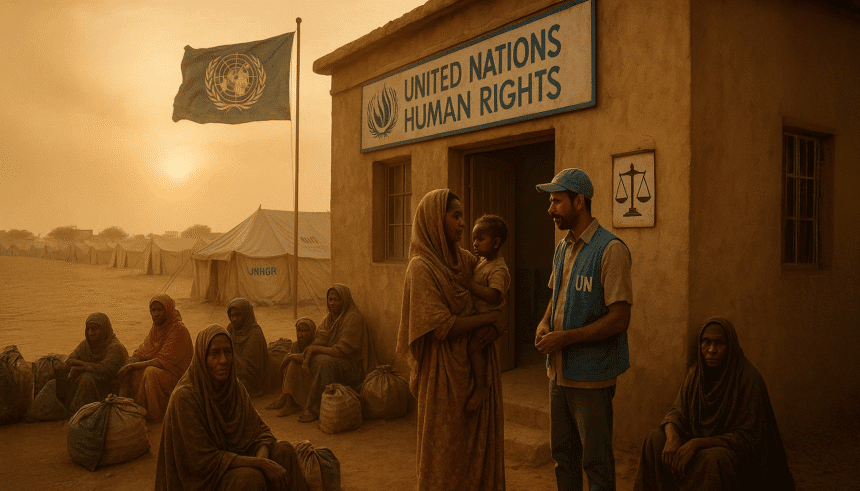

As the Sudan crisis spills deeper into neighboring Chad, Eastern provinces are buckling under the weight of a growing humanitarian emergency. In the dusty border town of Abéché, once a quiet outpost, tens of thousands of displaced people now arrive with stories of violence, fear, and loss. In response to the escalating crisis, the United Nations has opened a new human rights sub-office there, not just as a logistical move, but as a signal: that protection, dignity, and accountability must not be afterthoughts in the scramble to deliver aid.

The Context: Displacement in Eastern Chad

Eastern Chad has been under mounting pressure for years as conflict in neighboring Sudan, particularly Darfur, pushes waves of refugees across the border. At the close of 2024 the country hosted about 1.2 million refugees from Sudan, the Central African Republic, and Cameroon, plus many internally displaced persons. Many of these are women and children, and nearly all face inadequate access to basic services such as health, sanitation, education, and legal protection. The rapid influx combined with sparse resources has strained local capacities beyond breaking. UNHCR warns that existing border transit points, shelters, and settlements are overwhelmed.

What the New Office Offers: Capabilities and Limits

The Abéché sub-office is expected to bolster human rights monitoring, documentation and the protection of vulnerable groups. It may work to improve accountability for abuses, offer human rights advice and training, liaise with national authorities, and help strengthen legal frameworks for displaced persons. However, the new office does not solve bottlenecks such as resource scarcity, access challenges in remote areas, or the volatility in security that disrupts humanitarian operations. Given how many newly arrived people are arriving daily, the office will need strong logistical support, secure access, and steady funding to realize its mission.

Implications for Protection, Gender, and Local Systems

One major implication is in the realm of gender-based protection. Displacement research has shown that women and girls in camps and informal settlements in Eastern Chad suffer exposure to a variety of risks, from sexual violence during their journey to gaps in health or psychosocial services after arrival. The presence of a UN rights office could help with improving complaint mechanisms, reinforcing protection protocols, and ensuring that gender considerations are not sidelined.

For host and local communities, the office could mark a shift in how humanitarian and human rights actors engage with national systems. If the office partners with Chadian authorities, local civil society, and humanitarian agencies it may help build more sustainable models of service delivery rather than purely emergency relief. Accountability could improve, including for abuses by non-state actors or armed groups. It could also assist in documenting violations in ways that facilitate legal or policy change.

Risks and Challenges

Setting up a human rights office does not automatically guarantee impact. Security is a serious obstacle. Many of the displaced are in hard-to-reach areas where conflict, mobility constraints, and remote geographies limit access. Additionally, unless the office receives enough funding and personnel, monitoring may remain partial. There is also the risk of politicization or tension with national actors who may see human rights scrutiny as criticism rather than collaboration.

Further, there is competition among humanitarian priorities. The displacement crisis has pushed health, food, shelter, water, sanitation, education into urgent need. Human rights work is often underfunded in these settings. If donors do not prioritize this new office, it may struggle to make a difference.

Looking Forward: What Success Would Look Like

Success for this office would involve measurable improvements in protection outcomes: reductions in incidents of violence, especially gender-based, more timely access for displaced people to legal recourse, more robust documentation of rights violations, and positive feedback from refugees, returnees and IDPs about feeling safer and better supported. It would involve closer integration of human rights concerns into overall humanitarian planning.

It may also require the office to serve as a bridge between emergency humanitarian responses and longer-term development or rights-based work, so that when security allows, displaced people are not forever dependent on aid but can access durable solutions: safe return, local integration, or resettlement.

A Final Note

Establishing the Abéché sub-office is a necessary and welcome step in a protection landscape that has long been under-resourced. It addresses glaring gaps in human rights monitoring and response in Eastern Chad. However, the real test lies in whether this initiative can secure sufficient resources, ensure safe access, work closely with local actors, and translate human rights mandates into concrete improvements on the ground. With the right support this office could shift how displacement is managed in Eastern Chad, offering displaced people not just survival but dignity, protection and hope for durable solutions.