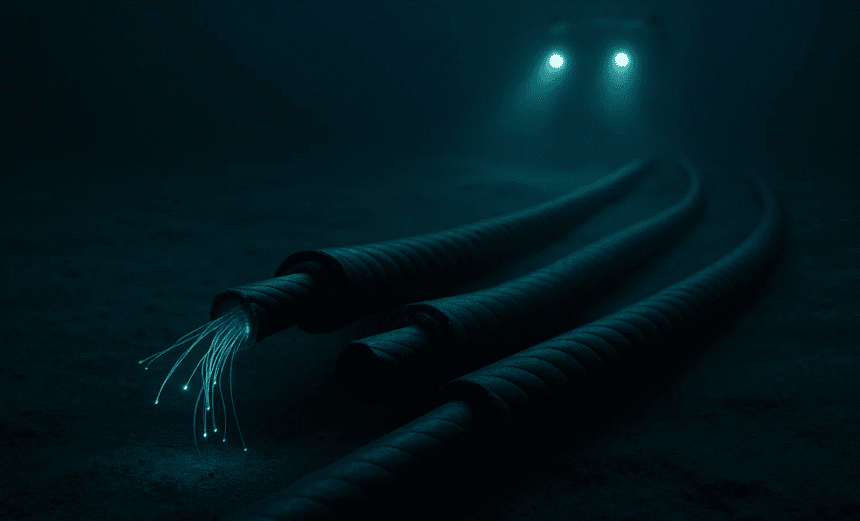

On September 6–7, 2025, a series of critical subsea fiber-optic cables were severed in the Red Sea, causing significant disruption to internet connectivity across Asia, the Middle East, and parts of Europe. The failures occurred near Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, and affected key systems including SEA-ME-WE 4, IMEWE, SMW4, and FALCON. The Red Sea has long been a vital artery for digital traffic, carrying over 90% of Europe-Asia communications. With several cables down, countries such as India, Pakistan, the United Arab Emirates, Saudi Arabia, and Kuwait experienced immediate slowdowns in internet speed, higher latency, and service degradation.

The Red Sea’s importance lies in its role as a chokepoint for global internet infrastructure. Much like the Suez Canal is essential to maritime shipping, this stretch of water is critical for digital trade. Its dense network of fiber-optic cables handles enormous amounts of data between continents, enabling everything from banking and cloud services to video streaming and international communications. A sudden break in multiple systems simultaneously sent ripple effects across nations, impacting both businesses and everyday users.

Technology companies and network operators scrambled to contain the fallout. Microsoft reported that its Azure cloud service was experiencing delays, particularly for users routed through the Middle East. To mitigate the issue, traffic was redirected through alternative paths, though not without performance costs. NetBlocks, which monitors global internet disruptions, reported reduced connectivity in India, Pakistan, and the UAE, with major providers like Etisalat and Du struggling to maintain stable service. Although the rerouting prevented a total blackout, millions of users faced slower internet speeds and interruptions in cloud-based applications.

As for the cause, there is still no confirmed explanation. Speculation ranges from maritime accidents, such as ship anchors dragging cables, to deliberate sabotage linked to regional tensions. While some Yemeni government officials blamed Houthi rebels, the group issued a statement denying involvement. For now, experts caution against concluding until repair teams can fully inspect the damaged sections.

Repairing subsea cables is no simple task. Specialized ships must be dispatched to locate the precise point of damage, often deep underwater, before remotely operated vehicles or divers can retrieve and mend the fiber. This process can take weeks under normal circumstances, and longer if geopolitical or weather conditions complicate access. With multiple cables affected, the recovery timeline may stretch even further. Past incidents in the region, including disruptions to the AAE-1 and PEACE cables in 2024 and 2025, required weeks or even months for full restoration.

The incident underscores the fragility of global digital infrastructure. A single event in one region has the power to affect connectivity across multiple continents, highlighting the risks of relying too heavily on narrow chokepoints like the Red Sea. Policymakers and technology companies may now accelerate investments in alternative routes, such as terrestrial “super-corridors” running through Turkey or the Arabian Peninsula, to reduce dependency on a single bottleneck.

Ultimately, while services will gradually stabilize as networks adapt and repairs get underway, the Red Sea cable cuts are a reminder that the internet, often perceived as seamless and indestructible, is deeply reliant on vulnerable physical infrastructure lying quietly on the ocean floor.