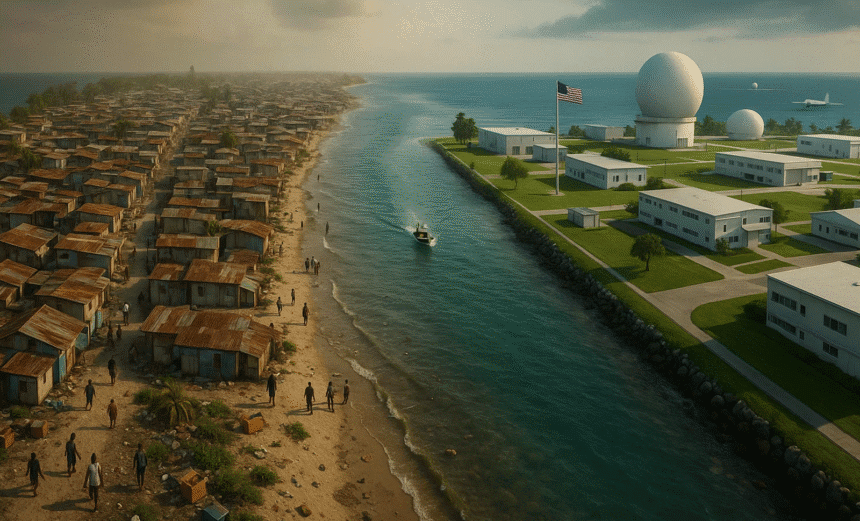

On a narrow strip of coral less than a mile long, the people of Ebeye bear the human cost of America’s strategic presence in the central Pacific. This island community of about 10,000 is the overlooked neighbor of the U.S. Army Garrison Kwajalein Atoll, a missile-test site that is one of Washington’s most important outposts in the Indo-Pacific. While the base projects American power across the ocean, Ebeye struggles with overcrowding, contaminated food, limited health care, and a chronic shortage of infrastructure. The contrast between the two islands illustrates how the Marshallese provide labor, land, and proximity while the United States secures its forward military edge.

The story of Ebeye is both historic and immediate. During the Cold War, entire Marshallese communities were displaced to make way for missile ranges and U.S. base construction. Today, many of their descendants live in cramped houses and makeshift shacks, separated from the pristine lawns, supermarkets, and medical clinics of Kwajalein by only a short boat ride. On the base, U.S. personnel enjoy air-freighted produce, reliable power, and advanced medical care. On Ebeye, nearly one-third of adults live with diabetes; there are no dialysis machines, and many reef fish, once a dietary staple, are poisoned by toxins like arsenic and PCBs. For locals, the proximity to the world’s most advanced missile-tracking radar is also proximity to a lifetime of environmental hazards and poverty.

Kwajalein’s importance stems from geography. Roughly 2,100 nautical miles southwest of Honolulu, the atoll gives the U.S. a vital platform for missile defense tests and tracking over the world’s largest ocean. Ebeye sits at the heart of this network, supplying labor and services that keep the installation running. That closeness has given the island a strategic role far greater than its size, but it has also concentrated the burdens of military dependence in a fragile community already facing the stress of climate change and sea-level rise.

The financial arrangements that underpin this relationship remain a point of contention. Washington has pledged billions of dollars to the Marshall Islands and the other Freely Associated States as part of renewed security agreements, with more than $100 million specifically promised for Ebeye. Past decades have seen hundreds of millions in compensation for nuclear testing and displacement, but Marshallese leaders argue that the payments fall far short of covering the loss of land, health, and cultural heritage. For many on Ebeye, the promise of new housing, water systems, and health upgrades is welcome but feels long overdue.

Economically, the base brings both opportunity and dependence. Many Ebeye residents work for the U.S. installation, drawing wages that flow into the local market. Shipping routes and regular flights connect the island to Majuro, 275 miles away, and beyond, ensuring some measure of connectivity to the wider world. Yet this connectivity is uneven. Imported goods dominate, especially shelf-stable processed foods that have displaced traditional diets and contributed to chronic disease. Fresh produce is scarce and expensive, cold storage is unreliable, and local fishing has been undermined by contamination. As a result, Ebeye’s families are locked into a cycle of dependence that sustains livelihoods but erodes long-term health.

The logistics of life on Ebeye reflect this imbalance. Goods arrive by ship or barge, and flights bring supplies to nearby airstrips before crossing causeways or reefs into the community. The same transport routes that keep the base stocked with American goods also dictate what is available to Marshallese families. When supply lines falter, the shortages hit Ebeye first. Even in the best of times, the everyday experience is one of cramped homes, erratic water service, and overburdened health facilities.

The human toll is visible in early mortality, untreated chronic illnesses, and the strain of living in an environment where opportunities are scarce and costs are high. For elders who remember their original home islands, the loss of land and lifestyle is a continuing wound. For the young, the lack of stable jobs, safe housing, and access to education or medical care shapes futures that feel limited. Local leaders emphasize that piecemeal fixes are not enough: only sustained investment in water security, medical facilities such as dialysis centers, housing programs, and environmental cleanup can ease the burdens Ebeye carries on behalf of U.S. strategy.

As Washington steps up its Pacific diplomacy in response to growing Chinese influence, the fate of Ebeye looms as a test of whether the United States can match strategic needs with genuine concern for human welfare. The island is small, but its story is vast, a reminder that great-power competition in the Pacific is also lived out in cramped homes, crowded clinics, and polluted seas. For now, Ebeye remains the community that pays for America’s Pacific edge.