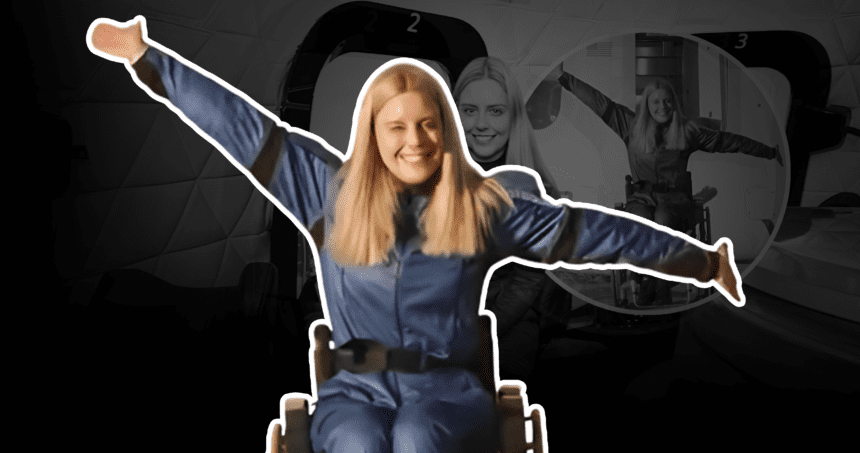

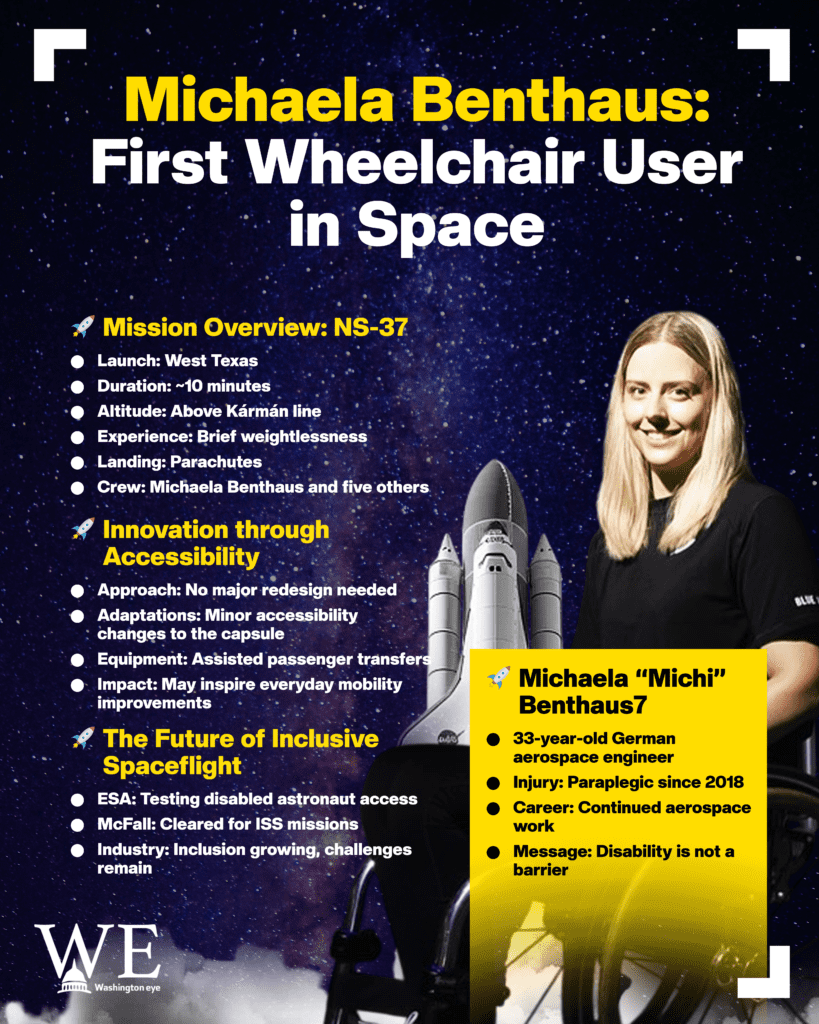

A German aerospace engineer has become the first wheelchair user to travel to space, after flying on Blue Origin’s New Shepard suborbital mission from West Texas on December 20, 2025, a milestone advocates say could accelerate efforts to make human spaceflight more inclusive. Michaela “Michi” Benthaus, 33, who uses a wheelchair following a spinal cord injury, joined five other passengers on the roughly 10-minute flight that rose above the internationally recognized boundary of space and delivered a brief period of weightlessness before returning to the desert landing site.

Blue Origin said the mission, its NS-37 crewed flight, lifted off from the company’s Launch Site One in West Texas after a short delay from an earlier target date, with a capsule carrying Benthaus alongside investor Joey Hyde, former SpaceX executive Hans Koenigsmann, entrepreneur Neal Milch, businessman Adonis Pouroulis, and space enthusiast Jason Stansell. The crew experienced a few minutes of microgravity, with the capsule reaching an apogee above the Kármán line before descending under parachutes.

Benthaus’s journey has drawn attention not only because it expands the profile of who can be a space traveler, but because it demonstrates how relatively small design and operational adjustments can widen access. Reporting around the flight noted that Blue Origin made minor accessibility adaptations, including equipment to help with transfers, rather than a wholesale redesign, a detail disability advocates highlight as a practical template for future commercial missions.

Her personal story has also resonated widely. Benthaus was injured in a 2018 mountain biking accident that left her paraplegic, yet she continued building a career in aerospace and pursuing space-related training opportunities. In interviews cited by multiple outlets, she framed the flight as both a personal achievement and a signal that disability should not automatically be treated as disqualifying in high-performance environments.

The reaction across the space community has been swift, with commentators pointing to the flight as a symbolic “first” that could have real operational consequences, especially as private suborbital flights increasingly act as proving grounds for new participation models. In Europe, the moment also lands amid a broader conversation about “fitness for flight” standards: the European Space Agency’s Fly! initiative has been testing pathways for astronauts with physical disabilities, and in 2025 the UK Space Agency said ESA astronaut John McFall had been medically cleared to become the first person with a physical disability eligible for a future long-duration ISS mission. While McFall’s case involves an amputation rather than wheelchair use, and he has not yet flown, the parallel underscores the direction of travel: widening the funnel for who gets to go.

For Blue Origin, the flight adds to a pattern of headline-making passenger selections aimed at broadening the public image of spaceflight, while also spotlighting the gap between “possible” and “routine.” Commercial suborbital missions remain expensive, and companies typically do not disclose seat prices, but advocates argue that representation at the top end of the market can still drive innovation in spacecraft interiors, medical screening protocols, training programs, and emergency procedures, changes that may later filter into professional astronaut corps standards and other high-risk transport sectors.

Benthaus’s supporters say the impact could extend beyond space. Accessibility experts often note that the same design thinking that enables an individual to transfer safely into a spacecraft seat, or navigate a capsule’s handholds in microgravity, can inspire improvements in everyday mobility systems on Earth. Benthaus herself has linked her flight to broader awareness goals, and coverage highlighted her interest in disability visibility and practical accessibility, not only in space hardware but in society more generally.

Still, the “first” comes with a challenge: ensuring it is not a one-off. Industry watchers say the next test will be whether commercial operators publish clearer accessibility standards, offer training pathways that accommodate different bodies, and normalize the presence of disabled flyers so that participation becomes less exceptional. For now, Benthaus’s short arc above Earth’s curvature has already expanded the boundaries of imagination, showing that the doorway to space can open wider than it has in the past.