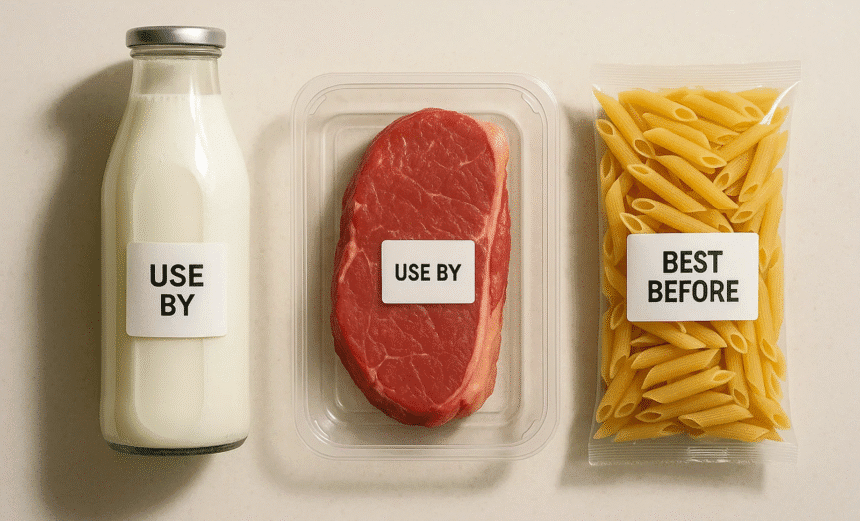

Each time consumers walk through grocery aisles, they are confronted with an important decision: whether or not to buy food products nearing their expiration dates. From milk cartons to pasta packages, expiration labels guide our choices, but do these dates actually matter as much as we think? Experts say the answer is more complicated than a simple “yes” or “no.” Expiration dates, often printed as “best before,” “use by,” or “sell by,” were introduced decades ago to standardize food quality and safety. However, the meaning behind each label is often misunderstood. “Best before” indicates when a product is at peak flavor and texture, not necessarily when it becomes unsafe.

“Use by” marks the manufacturer’s recommended last day for safe consumption, especially for perishable items like meat, dairy, and seafood. “Sell by” is aimed at retailers to manage shelf life, not consumers. The lack of global standardization has left many shoppers confused, leading to unnecessary food waste. According to the UN Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), nearly one-third of all food produced globally is wasted, and unclear labeling is a major contributor.

Not all expiration dates should be treated the same way. Highly perishable foods such as raw poultry, fish, and dairy can harbor harmful bacteria if consumed past their expiration dates. Illnesses like Salmonella, Listeria, or E. coli infections may result from ignoring “use by” guidelines. On the other hand, many packaged goods like dried pasta, canned beans, or rice remain safe long after their expiration date, though they may lose freshness or flavor. Food scientists emphasize that “expired” does not always mean “dangerous.” Instead, consumers should rely on their senses: check for unusual odor, texture, or mold growth before deciding.

One of the most pressing effects of strict adherence to expiration dates is the staggering amount of food waste. In the European Union alone, over 20 percent of household food waste is linked to confusion over date labeling. In the U.S., households throw away an estimated \$1,300 worth of food annually due to fear of expired products. This waste carries both economic and environmental costs. Wasted food means wasted resources: water, energy, land, and labor used to produce and transport food that never gets eaten. Moreover, food rotting in landfills contributes to methane emissions, a greenhouse gas more potent than carbon dioxide.

Expiration labels also influence consumer psychology. Shoppers often avoid discounted food close to its expiration date, perceiving it as inferior or unsafe. This behavior pressures retailers to discard perfectly edible items. Some initiatives, however, are changing consumer attitudes. Supermarkets in France and Denmark, for example, have launched campaigns encouraging customers to buy “ugly” or short-dated products at reduced prices. Apps like “Too Good To Go” allow consumers to purchase surplus food from restaurants and stores at a fraction of the cost.

Health experts and policymakers argue that reforming food date labeling could strike a balance between safety and waste reduction. Organizations such as the World Health Organization (WHO) and consumer advocacy groups recommend clearer, standardized terms worldwide. For instance, instead of multiple phrases like “sell by” or “best before,” a dual system could simplify matters: “Safe until” for health-sensitive perishables, and “Freshest before” for items where quality, not safety, is the issue. Education is also key. Teaching consumers how to store, check, and assess food can reduce unnecessary discards without compromising health.

The bottom line is that expiration dates do matter, but not always in the way we think. For perishable foods like milk, meat, and fish, expiration dates are crucial for health and safety. For shelf-stable goods, however, they act more as guidelines for optimal quality. Over-reliance on these dates without using sensory judgment has created a culture of waste. Consumers, retailers, and policymakers alike have a role to play in reducing confusion. By learning to read labels correctly and trusting their senses, consumers can save money, reduce waste, and still safeguard their health.