Parts of Germany’s Baltic Sea coastline have turned into a winter spectacle rarely seen in modern times, as sustained sub-zero temperatures have caused extensive ice formation along the shores for the first time in decades. From Schleswig-Holstein in the far north to Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania in the east, waterfronts that typically remain open in winter are now blanketed in thick ice, attracting both awe and concern from scientists, authorities, and the public alike.

The phenomenon began to emerge in late January 2026, when an unusually persistent cold wave gripped much of northern and eastern Europe. Frigid air masses moving south from Scandinavia and Russia pushed temperatures well below normal for weeks, with records in some areas dipping toward -15 °C and lower inland. Along the Baltic, where water temperatures usually hover just above freezing during winter months, the prolonged cold finally overwhelmed the sea’s natural resistance to freezing.

Typically, the Baltic Sea’s ice cover is confined to its northern reaches, such as the Gulf of Bothnia and Gulf of Finland, and only in especially harsh winters extend to more southerly areas. In its long recorded history, extensive ice has occasionally reached the coastline around southern Sweden and even parts of northern Germany, but such events have grown rarer over the past several decades as average winter temperatures have generally climbed.

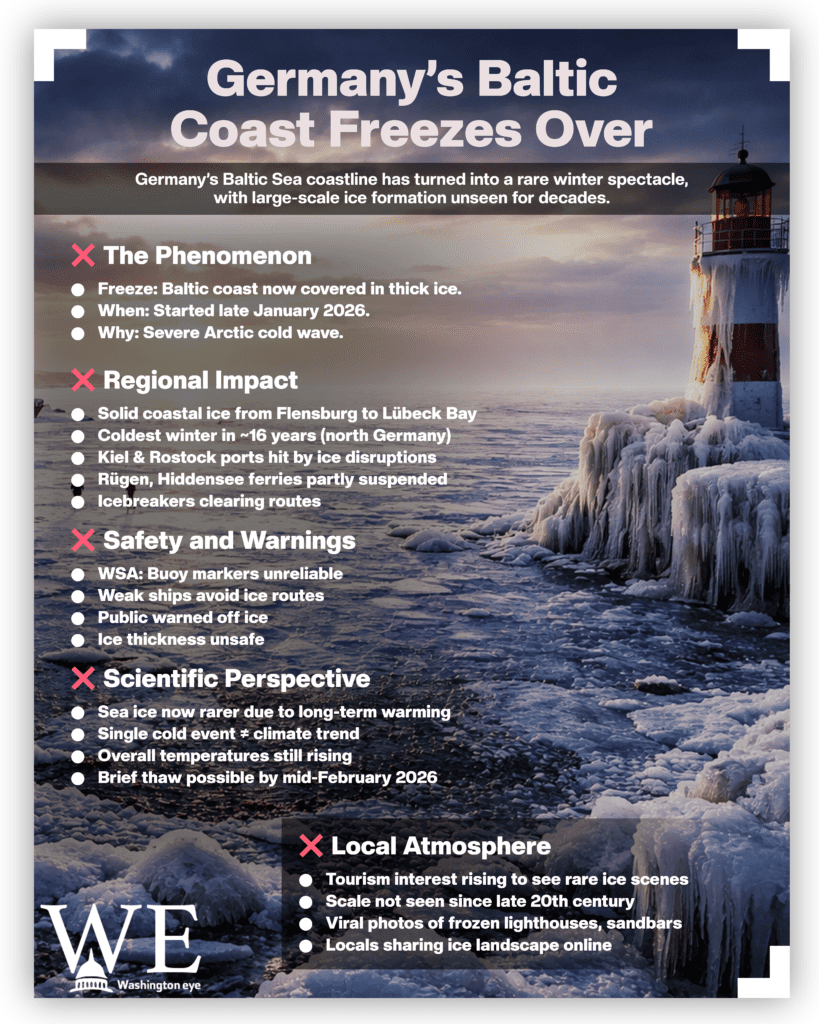

In 2026, however, the unusual strength and persistence of the cold spell led to a rare sight: solid sheets of ice forming along shallow coastal waters and sheltered bays. Satellite imagery and on-the-ground reports indicate that large stretches of coastline between Flensburg near the Danish border and the Bay of Lübeck were coated with ice by early February, with patches in some harbours solid enough for people to walk on cautiously.

Meteorologists say this winter qualifies as one of the coldest in at least 16 years across northern Germany, with weather services issuing extended frost warnings for the region. Even in ports like Kiel and Rostock, which rarely see more than floating ice fragments, solid ice floes have been reported, disrupting usual winter shipping operations.

The low water temperatures and ice formation have compelled coastal authorities to issue formal warnings. In early January 2026, the Baltic Sea Waterways and Shipping Authority (WSA) alerted mariners and ferry operators to the onset of ice, describing buoy systems as unreliable and urging heightened caution for vessels without ice-strengthened hulls. Ferry services to some of the smaller islands, such as Hiddensee and Rügen, have faced partial suspensions as icebreakers attempt to maintain navigable channels.

Local reactions have been mixed. For residents and visitors, the icy landscape has provided an unusual winter backdrop, families and photographers have been spotted taking careful strolls across frozen sandbars, while social-media posts and images of ice-clad lighthouses have circulated widely. Yet emergency services have also reiterated warnings about the danger of venturing out onto thin or unstable ice, which can vary widely in thickness.

Scientists monitoring the Baltic environment point out that, while occasional winter ice formation is not unheard of historically, this year’s broad coastal freezing is notable precisely because of how long such conditions have been absent in living memory. Over the last several decades, warming trends have reduced the frequency and extent of sea ice in southern Baltic waters, part of a broader European warming pattern documented in long-term climate data.

Yet climate experts caution against reading too much into a single cold winter. “Individual extreme events like this tell us about weather patterns at a moment in time,” one atmospheric scientist explained, “but they occur against the backdrop of larger climate shifts that still show long-term warming trends.” As a result, such freezes may remain rare, even as variability in winter weather increases.

In practical terms, the ice has brought both logistical challenges and economic impacts. Coastal shipping firms are adjusting schedules, while tourism businesses along the Baltic resorts are capitalising on the rare winter scenery. Hoteliers in seaside towns report increased interest from visitors keen to witness the frozen sea, a spectacle not seen at this scale since the winters of the late 20th century.

As February progresses, weather models suggest a brief thaw could arrive mid-month, bringing milder temperatures temporarily to the region. Yet for now, the German Baltic coast remains in an icy grip, a vivid reminder of nature’s capacity to surprise even in an era of warming oceans.