The U.S. Department of Defense has released its latest annual assessment of China’s armed forces, warning that Beijing’s nuclear modernization, while showing signs of slower warhead growth, continues to expand in ways that could raise crisis risks and complicate deterrence in the Pacific. The unclassified report to Congress, published on December 23, 2025, is the Pentagon’s yearly China Military Power Report, a style overview of military and security developments involving the People’s Republic of China.

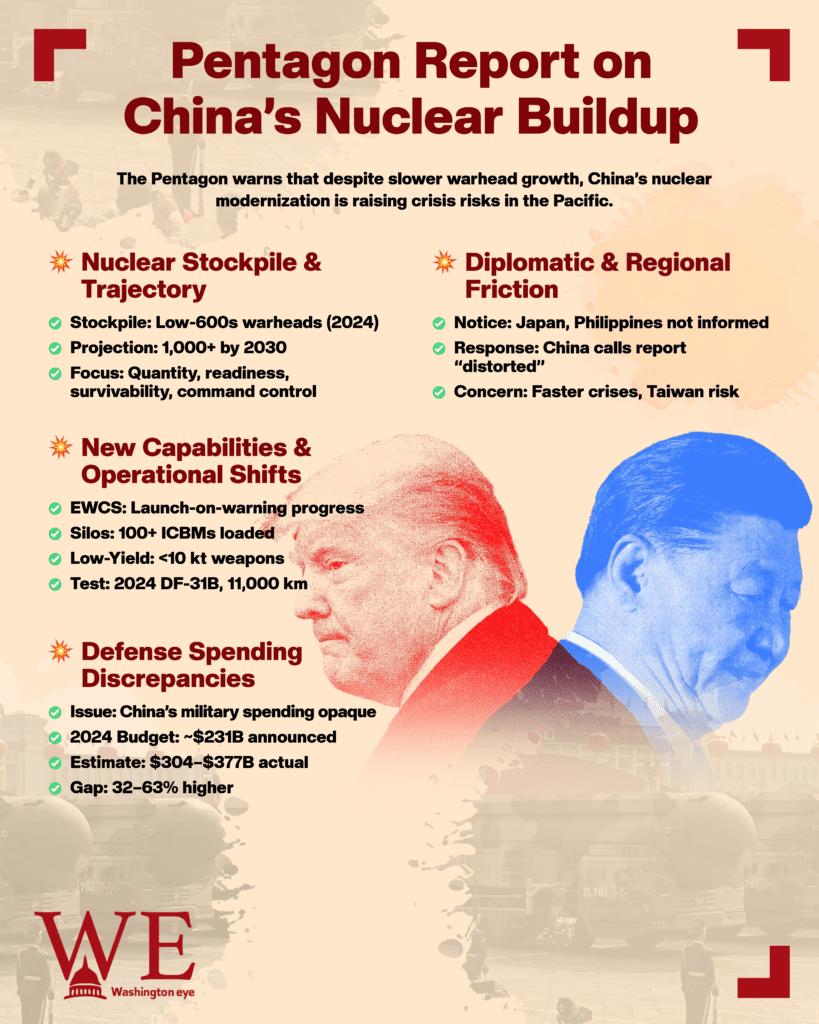

A central headline is the size and trajectory of China’s nuclear stockpile. The Pentagon assesses that China’s stockpile of nuclear warheads “remained in the low 600s through 2024,” reflecting a slower production pace than in prior years, but still projects Beijing is “on track” to field “over 1,000 warheads by 2030.” The report frames this as part of a “massive nuclear expansion” that is no longer only about quantity, but also about readiness, survivability, and command-and-control resilience.

The Pentagon’s deeper concern is that China appears to be building a posture that can respond faster in a crisis, potentially before a first strike lands. The report says China “probably made progress” in 2024 toward an early-warning counterstrike (EWCS) capability, akin to launch-on-warning concepts, where warning of an incoming strike could enable a retaliatory launch before detonation. It adds that China likely will keep refining and training on this through the decade. To support that, the report points to both space-based and ground-based sensors, including additional launches of early-warning satellites with likely infrared payloads and large phased-array radars designed to detect ballistic missiles at long range.

Operational activity highlighted in the report has also drawn attention. It notes that in September 2024 China launched an unarmed intercontinental ballistic missile into the Pacific Ocean for the first time since 1980, described as practice for a wartime nuclear deterrence operation and a way to verify full-range performance. The report says the DF-31B flew roughly 11,000 km and impacted the ocean near French Polynesia, and that China pre-notified some countries but did not notify Japan or the Philippines.

Another detail likely to fuel debate in Washington is the report’s claim that the PLA has “likely loaded more than 100” solid-propellant ICBM silos at its three silo fields with DF-31 class missiles, capabilities the report ties to EWCS operations and rapid launching. The report also says China is “probably pursuing” nuclear weapons with yields below 10 kilotons, which it argues could enable “limited” nuclear counterstrikes against military targets and help Beijing manage escalation.

Beyond warheads, the report spotlights a familiar U.S. concern: opacity in China’s defense resources. While Beijing’s announced 2024 defense budget is listed at about $231 billion, the Pentagon estimates China’s total defense spending in 2024 was “probably approximately $304–$377 billion,” or 32–63% higher than the announced figure, when accounting for categories such as the People’s Armed Police, provincial spending, mobilization, R&D, and other items. This “actual worth” gap matters, U.S. analysts argue, because it suggests Beijing can sustain modernization even when headline budget figures appear more modest.

China’s public response has been sharply critical. In Beijing, Foreign Ministry spokesperson Lin Jian urged the United States to fulfill its own nuclear disarmament responsibilities, saying China does not engage in nuclear arms races and arguing Washington should create conditions for other nuclear-weapon states to disarm. Separately, China criticized the Pentagon for what it called distortion of its defense policy in other areas referenced by the report, underscoring how politically sensitive such U.S. assessments have become.

For U.S. planners, the report’s bottom line is less about a single number and more about the direction of travel: a larger, more diverse arsenal; improved early warning; more credible second-strike options; and a posture that could compress decision time in a fast-moving crisis, especially one involving Taiwan or U.S. forces operating near China.