For decades, the U.S. dollar has reigned supreme as the world’s primary reserve currency. It serves as the bedrock of global trade, investment, and finance. From oil pricing and international loans to foreign reserves and cross-border settlements, the dollar’s dominance is unmatched. This monetary supremacy is not simply a reflection of America’s economic strength, but also of the deep trust placed in its institutions, transparent markets, and political stability. In contrast, China’s yuan—despite the country’s rising economic power—remains a distant challenger. As China continues to rise on the global stage, the question arises: Can the yuan realistically overtake the dollar and lead the world economy? As it stands today, the answer remains no, though the future could bring significant shifts.

The Chinese government has taken several strategic steps to internationalize the yuan. These include establishing bilateral currency swap agreements with more than 30 countries to reduce reliance on the dollar in trade, launching the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) which encourages trade and infrastructure development in yuan, and investing in digital finance through the development of a central bank digital currency (e-CNY). In 2016, the International Monetary Fund included the yuan in its Special Drawing Rights (SDR) basket, symbolically recognizing it as a global reserve currency alongside the dollar, euro, pound, and yen. These are not minor achievements—they indicate China’s intent and its global ambition to shape the future financial order.

However, currency leadership requires more than economic ambition. It requires deep, open, and trusted financial markets, a predictable legal system, political neutrality, and full convertibility—areas where China falls short. The Chinese economy, while the world’s second-largest, operates under heavy state influence. Capital controls are still in place, meaning money cannot freely move in and out of the country without regulatory oversight. This makes the yuan unattractive for investors and central banks who seek liquidity, legal security, and freedom from political interference. Furthermore, China’s legal and regulatory systems lack transparency, and decisions are often guided by political priorities rather than market principles. This undermines the confidence required for a currency to be globally dominant.

Trust is the single most crucial factor in currency power, and the yuan faces a significant trust deficit. The U.S. dollar, despite America’s political dysfunction or economic imbalances, still benefits from the world’s trust in its institutional integrity. Central banks, investors, and businesses feel safer holding dollars because they can access it anytime, anywhere, and under stable legal conditions. In contrast, China’s political system is opaque, and financial decisions can be arbitrarily reversed or influenced by the Communist Party. The fear that the Chinese government could freeze assets or impose sudden policy shifts makes global actors hesitant to fully embrace the yuan.

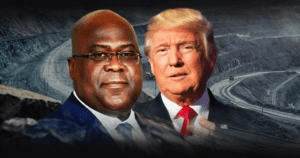

Geopolitics also plays a central role. The U.S.-China rivalry, along with sanctions and rising protectionism, has further complicated China’s push for a global yuan. While China has successfully convinced some partners—such as Russia and certain Gulf nations—to settle energy deals in yuan as part of a dedollarization effort, these instances remain isolated and strategic rather than systemic. The dollar, by comparison, is embedded in every corner of the global financial system. Most global commodities are priced in dollars, and the vast majority of international financial transactions pass through dollar-denominated accounts.

Looking ahead, the possibility of a multipolar currency world is more realistic than the yuan completely overtaking the dollar. As global power fragments and countries seek alternatives to mitigate risk, the yuan may increase its share in global trade and finance, especially among countries skeptical of U.S. dominance. However, a currency does not gain global leadership simply through political will or economic size—it must be earned through consistency, legal clarity, and open institutions. Unless China radically reforms its financial governance, ensures full convertibility, and builds long-term trust with the world, the yuan is unlikely to replace the dollar as the global leader.

In conclusion, while China’s efforts to expand the yuan’s international role are deliberate and growing, they are still constrained by structural and political limitations. The U.S. dollar’s dominance, deeply rooted in institutional credibility and global trust, will not be easily displaced. The yuan may rise in influence, particularly within China’s sphere, but as things stand, it is not yet equipped to lead the world. Currency power is not just about economic heft—it is about trust, transparency, and openness, all of which remain significant challenges for China.