The United States and Israel are reportedly exploring the idea of Washington leading a temporary post-war administration in Gaza, according to individuals familiar with the matter. The talks center around forming a transitional government led by a U.S. official that would take control of Gaza until the territory has been demilitarized, stabilized, and a viable Palestinian government can be put in place.

The concept draws parallels with the Coalition Provisional Authority (CPA) that governed Iraq after the 2003 U.S.-led invasion. While early-stage and lacking a fixed timeline, the Gaza proposal would also likely exclude Hamas and the Palestinian Authority, instead relying on Palestinian technocrats and potential participation from moderate Arab states.

The CPA, led by L. Paul Bremer from May 2003 to June 2004, was tasked with governing Iraq in the wake of Saddam Hussein’s ouster. Officially called the Administrator of the Coalition Provisional Authority, Bremer wielded sweeping executive, legislative, and judicial powers. His role closely resembled that of a medieval viceroy—a historical figure who acted as the monarch’s representative in distant territories, overseeing both civil governance and military affairs.

In medieval and early modern times, viceroys were typically dispatched to rule over colonies or contested regions. Their job was to maintain the authority of the crown, implement policies, and manage local affairs. Much like Bremer’s authority in Iraq, these viceroys often ruled with absolute power, answering directly to the sovereign but operating with a high degree of autonomy on the ground.

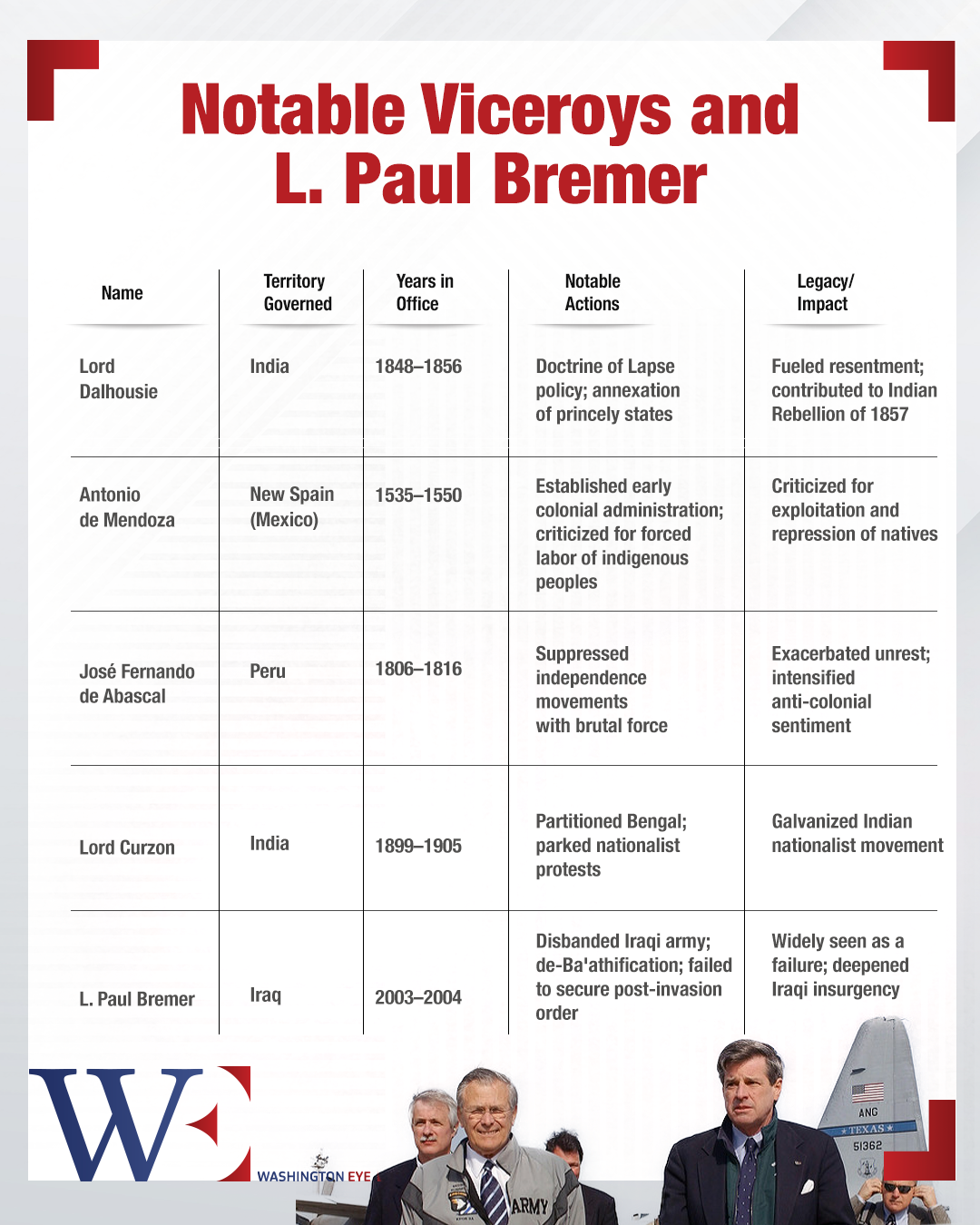

While viceroys were meant to serve as loyal stewards of empire, many became infamous for poor governance, corruption, or heavy-handed tactics. Some notable examples include:

– Lord Dalhousie, India (1848–1856): As Governor-General of India, a role similar to a viceroy, Dalhousie pursued aggressive policies of annexation under the Doctrine of Lapse, which allowed the British to seize territories from local rulers who died without a male heir. His expansionist policies fueled deep resentment, contributing to the outbreak of the Indian Rebellion of 1857.

– Antonio de Mendoza, New Spain (1535–1550): The first viceroy of New Spain (now Mexico), Mendoza initially earned praise for stabilizing the colony but later faced criticism for harsh treatment of indigenous peoples and the forced labor systems implemented under his watch.

– José Fernando de Abascal, Peru (1806–1816): Abascal’s tenure as viceroy of Peru was marked by brutal repression of independence movements. His severe policies only deepened the resolve of rebels seeking liberation from Spanish rule, further destabilizing the region.

– Lord Curzon, India (1899–1905): Known for his intelligence and administrative reforms, Curzon is also remembered for his controversial decision to partition Bengal in 1905, which sparked widespread protests and intensified anti-British sentiment.

Bremer’s CPA in Iraq is now seen as a cautionary tale of how transitional governance can go wrong. By disbanding the Iraqi Army, purging the bureaucracy through de-Ba’athification, and failing to restore law and order effectively, the CPA alienated Iraqis and fueled insurgency. Despite its mission to rebuild Iraq, the CPA’s perceived status as a foreign occupation government deepened divisions and stoked resistance.

Like viceroys of old, Bremer was granted sweeping authority with the aim of stabilizing a fractured region. Yet his tenure demonstrated that ruling by decree without adequate local legitimacy and understanding of the social fabric can have disastrous consequences.

The current discussions about Gaza raise similar concerns. Any transitional authority would face the immense challenge of balancing military security with the need for political legitimacy. Excluding both Hamas and the Palestinian Authority could leave a vacuum of local leadership, and relying solely on technocrats risks overlooking the political dynamics on the ground.

Israeli Foreign Minister Gideon Saar has already floated a vision for a transitional period, suggesting an international board of trustees that would include moderate Arab countries working alongside Palestinians under their guidance. Such a framework could broaden regional legitimacy, but persuading Arab states to participate—especially under a U.S.-led initiative—may be diplomatically challenging, particularly given the sensitivities around Israel’s military actions in Gaza.

Another key concern is the selection of the lead administrator. Just as Bremer operated as a modern-day viceroy, the Gaza authority would likely require a figure with significant diplomatic and crisis management experience. However, history shows that no amount of administrative skill can substitute for local legitimacy and grassroots buy-in. The CPA’s legacy reveals the dangers of relying too heavily on foreign experts while marginalizing local voices.

Any transitional authority in Gaza would also need to set clear, transparent milestones for demilitarization, reconstruction, and the eventual handover of power. One of the main criticisms of the CPA was its lack of clear benchmarks and timelines, which led many Iraqis to believe that the U.S. intended to occupy their country indefinitely. In Gaza’s case, the absence of defined goals could generate similar distrust and potentially exacerbate tensions on the ground.

A robust security apparatus, built with vetted local recruits, would be essential for maintaining order. Yet balancing security with civil rights and ensuring that basic services—such as electricity, clean water, and medical care—are consistently delivered would be equally critical in winning hearts and minds.

The path forward remains uncertain. Both U.S. and Israeli officials have refrained from publicly confirming the details of these discussions. But if history offers any guidance, the stakes are high. Transitional administrations can either serve as bridges to peace and self-rule or become symbols of foreign domination and mismanagement.

History provides clear lessons: transitional authorities and viceroy-like roles may temporarily impose order but often fail when they lack deep local engagement and legitimacy. Whether in colonial India, Spanish America, or post-war Iraq, foreign-led governance has repeatedly sparked backlash, particularly when local grievances are ignored or mismanaged.

If the U.S.-led Gaza proposal moves forward, it will need to learn from these historical missteps. Any administrator must prioritize inclusive governance, clear milestones for transition, and respect for local agency. Without these, the effort risks being remembered not as a bridge to peace but as yet another chapter in the troubled history of foreign intervention.