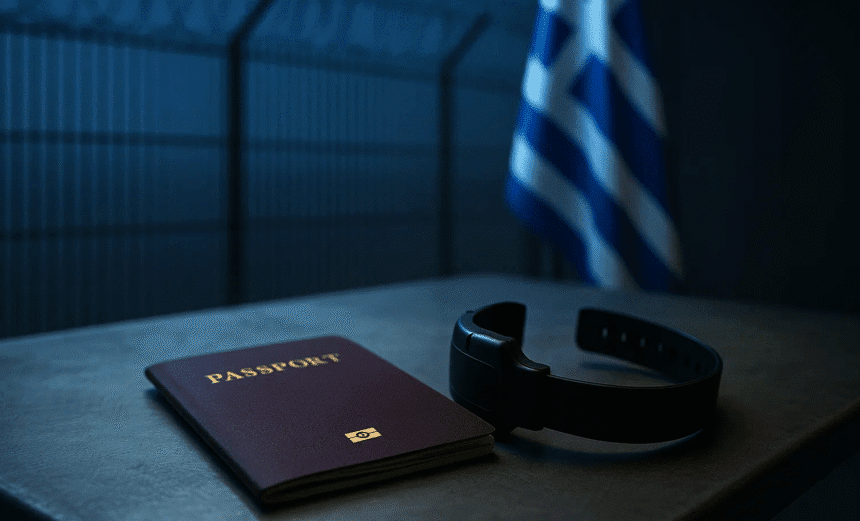

Greece’s parliament has approved a sweeping new law that imposes harsh penalties on rejected asylum seekers, marking one of the toughest migration policies in the European Union. The legislation, adopted on September 3 and reported widely on September 4, gives unsuccessful applicants just 14 days to leave the country. If they fail to comply, they face prison sentences of between two and five years, fines of up to €10,000, and detention periods that can last as long as 24 months. In addition, authorities may use electronic ankle monitors during a 30-day post-appeal period, with violations leading to criminal charges.

The new law comes amid a sharp increase in migrant arrivals from North Africa, particularly from Libya to Crete and the smaller island of Gavdos. Greece’s center-right government argues that the country can no longer afford to accommodate rising numbers of undocumented migrants and must protect its borders as well as its citizens. Migration Minister Thanos Plevris made the government’s stance clear: “If your asylum request is rejected, you have two choices. Either you go to jail or return to your homeland.” In line with this message, the government has doubled detention limits from 18 to 24 months, significantly increased fines, and introduced measures intended to accelerate deportations.

The law also removes pathways to legalization for migrants who have lived in Greece without papers for more than seven years, stripping them of the chance to regularize their status in the future. While the government insists this is necessary to deter illegal migration, it also provides a voluntary return incentive of €2,000 for those who agree to depart on their own, hoping to encourage self-deportation and reduce pressure on overcrowded detention centers.

The groups most directly affected by the legislation are asylum seekers from EU-designated “safe countries,” undocumented migrants awaiting administrative processing, and long-term residents who have survived for years in legal limbo. For many, the changes mean facing detention, financial ruin, or forced removal. Human rights organizations warn that the measures effectively criminalize migration, punishing individuals who may have fled war, persecution, or poverty.

Reaction to the new law has been polarizing. The government frames it as “tough but fair,” calling it a necessary step to manage migration flows and safeguard Greek society. Critics, however, argue that it undermines human rights and international refugee protections. The UNHCR has urged Greece to avoid penalizing vulnerable people and instead focus on fast-tracking asylum procedures to ensure fair treatment. The European Court of Human Rights has already intervened in some cases, halting deportations and demanding that applicants be given access to proper asylum reviews.

Advocates for refugees inside Greece were quick to condemn the legislation. Lefteris Papagiannakis of the Greek Council for Refugees called it “inherently racist,” accusing the government of exploiting migration fears to court far-right voters. Some judges and opposition lawmakers described the bill as “antisocial” and “inhuman,” warning that it would foster “lawlessness” rather than order. International analysts compared the policy shift to “Trump-style” immigration tactics in the United States, with detention centers in Greece already earning nicknames such as “the Aegean Alcatraz” for their harsh conditions.

The law’s passage also raises broader questions about Europe’s migration policy. Frontex, the EU’s border agency, is already investigating at least a dozen potential human rights violations linked to pushbacks in Greek waters. Critics fear that this legislation will only deepen concerns about violations of international law. Yet, for the government, the message is unambiguous: Greece is tightening the screws on migration and will no longer tolerate the prolonged stay of those who fail to secure asylum.

As Greece doubles down on deterrence, it stands at a crossroads between national security and humanitarian obligation. While the new law may appeal to voters anxious about rising arrivals, it risks isolating vulnerable people further and placing Greece at the center of Europe’s contentious debate on migration.