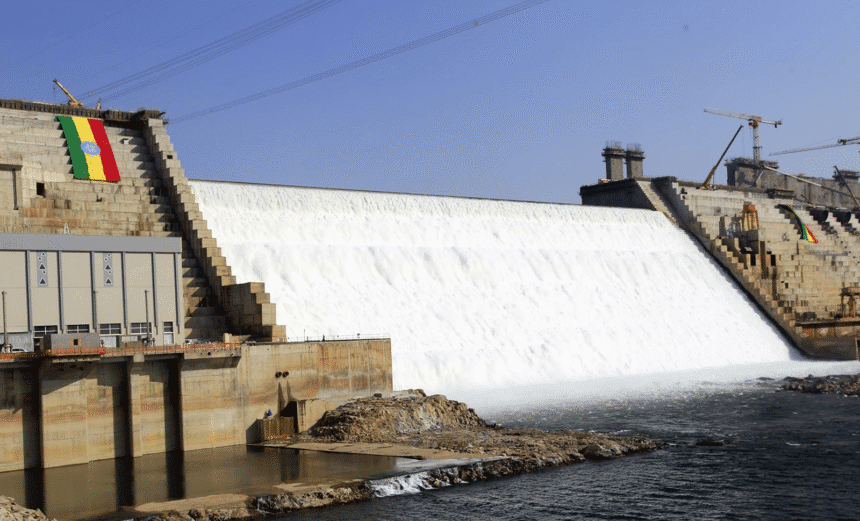

On 9 September 2025, Ethiopia inaugurated the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD), Africa’s largest hydroelectric project, despite lingering tensions with downstream neighbors Egypt and Sudan. The opening ceremony, held in the Guba district of the Benishangul-Gumuz Region near the Sudanese border, marked the culmination of nearly 15 years of work on a project that has been hailed as a symbol of Ethiopia’s resilience and criticized as a potential flashpoint in one of the world’s most sensitive river basins.

The GERD, first launched in 2011, stands 145 meters tall and stretches 1.8 kilometers across the Blue Nile. Its vast reservoir can hold up to 74 billion cubic meters of water, almost equivalent to the annual flow of the Blue Nile itself. Once fully operational, the dam is expected to generate over 6,000 megawatts of electricity, doubling Ethiopia’s current capacity and positioning the country as an energy hub for East Africa. Officials in Addis Ababa say the project will bring electricity to millions who live without reliable power, spur industrialization, and allow Ethiopia to export surplus electricity to neighbors such as Kenya, Sudan, and Djibouti.

For Ethiopians, the \$5 billion GERD has become a matter of national pride, funded largely through bonds and domestic contributions rather than foreign loans. At the opening ceremony, Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed described the project as “a new dawn for Ethiopia and for Africa,” declaring that it represented independence from external pressure and a decisive step toward poverty reduction. Crowds celebrated in Addis Ababa and other cities, waving flags and singing patriotic songs as news of the inauguration spread.

But the mood was far less jubilant in Cairo and Khartoum. Egypt, which depends on the Nile for more than 90 percent of its freshwater needs, has consistently expressed fears that the GERD could reduce the river’s flow and threaten the livelihoods of its 110 million people. The country’s agricultural sector, already under stress from climate change and population growth, faces particular risk if water levels drop during drought years. Egyptian Foreign Minister Sameh Shoukry reiterated after the opening that “water is life for Egypt” and warned that Cairo would not accept any threat to its “existential interests.”

Sudan, lying between Ethiopia and Egypt, has taken a more nuanced stance. On one hand, officials in Khartoum see benefits in the form of regulated water flow, reduced flooding, and access to cheaper electricity imports. On the other hand, they worry about dam safety and the lack of a binding agreement to coordinate water releases. Without such a framework, Sudan fears sudden reductions in water during dry periods or risks if the dam’s structure were ever compromised.

At the heart of the dispute is the question of who controls the Nile. Egypt and Sudan base their claims on colonial-era treaties from 1929 and 1959, which granted them the lion’s share of the Nile’s water while excluding upstream states like Ethiopia. Addis Ababa rejects these agreements as outdated and unjust, arguing that it has every right to develop its own resources. Ethiopia insists that the filling of the GERD’s reservoir has been carefully managed to avoid significant downstream harm, while Egypt argues that without a binding deal, such assurances cannot be trusted.

International mediation has so far failed to break the deadlock. Over the past decade, the African Union, the United Nations, and the United States have all attempted to broker agreements, but efforts have faltered over issues of water allocation, drought management, and dispute resolution. Following the dam’s inauguration, African Union Chairperson Moussa Faki Mahamat congratulated Ethiopia but urged dialogue, stating that “shared rivers must unite, not divide. Only cooperation can unlock the Nile’s full potential.” Western governments offered cautious praise for Ethiopia’s achievement while emphasizing the importance of regional stability, and China, a major investor in African infrastructure, applauded Ethiopia’s determination to fund and complete the project largely on its own.

The GERD’s impact on the region will unfold over the coming years. For Ethiopia, it promises transformational benefits, millions gaining access to electricity, a growing industrial sector, and new streams of foreign exchange through power exports. For Sudan, it could bring both opportunities and risks, smoothing out the Nile’s seasonal flow but raising questions about safety and sovereignty. For Egypt, it represents an enduring threat to water security, with fears that prolonged droughts or mismanagement of the reservoir could devastate farms and cities. Environmental experts also caution that the dam may alter ecosystems, affect fisheries, and accelerate evaporation, though Ethiopia argues that its highland location minimizes such risks.

As turbines begin to spin and electricity flows from the GERD, Ethiopia celebrates a milestone that it views as long overdue. Yet the opening also underscores unresolved disputes that could flare into regional conflict if not carefully managed. The Nile remains a lifeline for hundreds of millions, and the challenge ahead lies not only in generating power but in finding power-sharing solutions that balance development, security, and survival.