The recent confirmation by U.S. Energy Secretary Chris Wright that Washington and Riyadh are actively progressing toward a civil nuclear cooperation agreement marks more than just a policy milestone — it signals a strategic recalibration in the balance of power across the Middle East. This proposed deal, still in its early stages, holds the potential to reshape the geopolitical and security architecture of the region. At its heart lies a central question: what happens when the last major regional power without nuclear infrastructure begins building one, and under the guidance of the United States?

The Strategic Incentives Behind the Deal

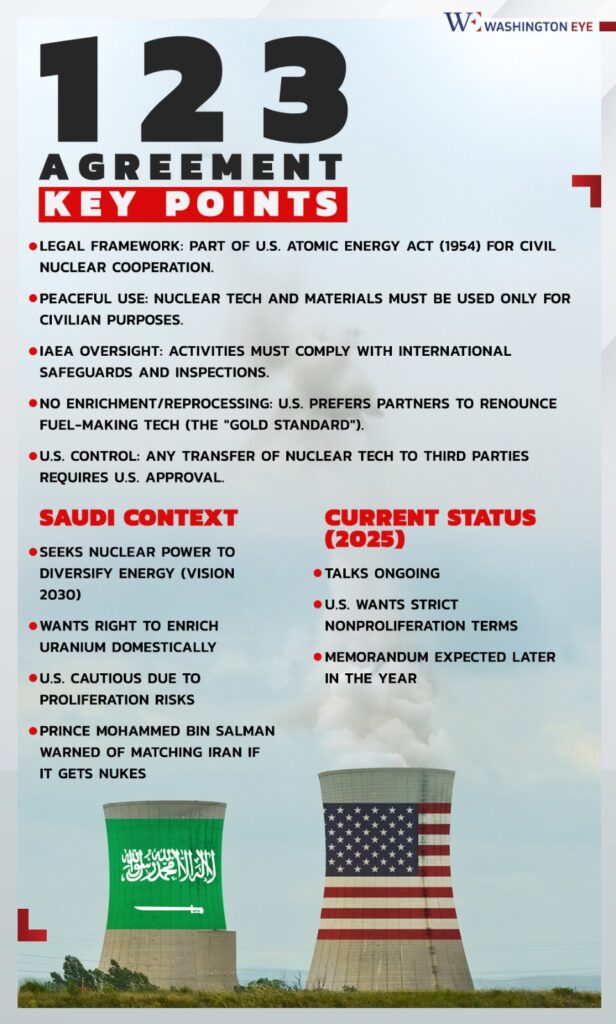

The discussions center around a “123 Agreement,” the legal framework under which U.S. entities can share nuclear technology for peaceful purposes, such as power generation and desalination. However, talks have reportedly stalled on two key U.S. conditions — Saudi Arabia’s acceptance of restrictions on uranium enrichment and the reprocessing of spent fuel, both of which are considered sensitive technologies due to their potential use in developing nuclear weapons. Riyadh, thus far, has refused to rule these out entirely, citing energy sovereignty and regional security concerns, according to Reuters.

Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman’s past statement that the Kingdom would pursue nuclear weapons if Iran acquires them continues to loom over these negotiations. While the U.S. frames the deal as a step toward “clean energy” collaboration, many experts see it as an effort to keep Saudi Arabia aligned with Western norms and prevent it from seeking assistance from China or Russia, both of whom have fewer safeguards on proliferation.

A Region Already Treading the Nuclear Line

While Saudi Arabia is a late entrant in the nuclear conversation, the region is no stranger to atomic ambitions. Israel, though refusing to officially confirm its arsenal, is widely acknowledged to possess a sophisticated nuclear weapons program, developed in secrecy since the 1960s. It remains the only country in the region with such an undeclared but functional deterrent, and its ambiguous posture has long served to deter both state and non-state threats.

Iran, by contrast, occupies the spotlight in global non-proliferation debates. Since the U.S. withdrawal from the 2015 nuclear deal (JCPOA) under the Trump administration, Tehran has steadily increased its enrichment activities. Currently, it is enriching uranium up to 60% purity—just short of weapons-grade—and has amassed stockpiles far beyond the JCPOA limits. This has provoked deep unease in Gulf capitals, particularly Riyadh, which views Iran’s nuclear trajectory as an existential threat.

In the Gulf, the United Arab Emirates offers a contrasting model. The UAE’s Barakah nuclear plant, built with South Korean assistance, operates under some of the strictest non-proliferation standards in the world. Abu Dhabi voluntarily renounced domestic enrichment and reprocessing, setting what the U.S. often refers to as the “gold standard” of nuclear agreements. If Saudi Arabia demands more flexibility than the UAE accepted, it may fuel concerns that the Kingdom seeks more than just peaceful nuclear energy.

Egypt and Turkey as well are moving toward nuclear energy. Egypt’s El Dabaa power plant, under construction with Russian backing, reflects Cairo’s desire to diversify its energy sources and expand its strategic independence. Turkey, through a deal with Russia’s Rosatom, is constructing the Akkuyu nuclear plant and has previously expressed interest in developing enrichment capabilities.

The Larger Strategic Chessboard

Saudi Arabia’s insistence on domestic enrichment could also be a hedge against future U.S. policy reversals. After the unpredictability of American foreign policy in the Trump era and the faltering nuclear negotiations with Iran, Gulf states are keen to retain maximal leverage. Enrichment capabilities — even if not immediately weaponized — offer a long-term insurance policy.

The U.S., meanwhile, finds itself in a delicate balancing act. Granting enrichment rights to Saudi Arabia could undermine the very non-proliferation norms Washington has championed for decades. But denying them may drive Riyadh toward Beijing or Moscow, deepening America’s strategic decline in the region.